Art cases in the English courts tend to generate more than their fair share of interest, even fascination, among litigators, judges, the media and the public at large. Attribution cases, in which the authorship, date or origin of artworks or other cultural property are questioned, are especially packed with both art and general historical detail, often with intrigue and the need for Holmesian deductive powers mixed in, and then all on display in the trial arena. They sometimes even call for the expertise of the real historian – thus Mr Jonathan Sumption QC (as he then was) respectfully telling the Court of Appeal, at the hearing of Christie’s appeal in Thomson v Christie’s (2005) that he ‘would not want your Lordships to be embarrassed in the senior common rooms of our great universities’. A member of the Court had ventured an (incorrect) observation on the relationships between the 18th Century ducal court of Parma, where the design for the gilt bronze and porphyry urns the subject of the case had first appeared, and the Bourbon dukes of France.

This article is no more than a speedy and rough tour d’horizon of the better known attribution cases, from Desenfans v Vandergucht (1787) to Sotheby’s v Weiss (2019), with a flavour – given the readership – of the legal issues which they throw up.

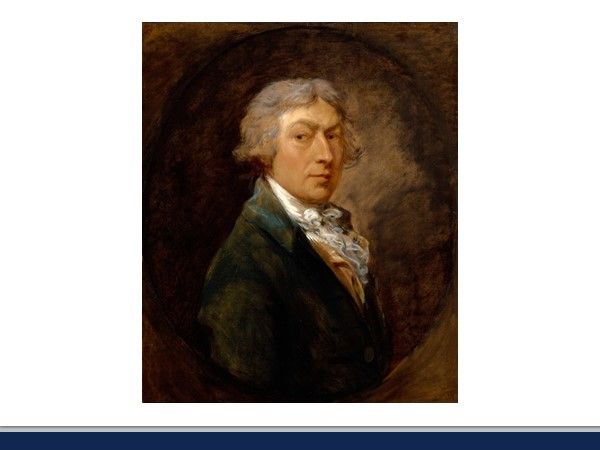

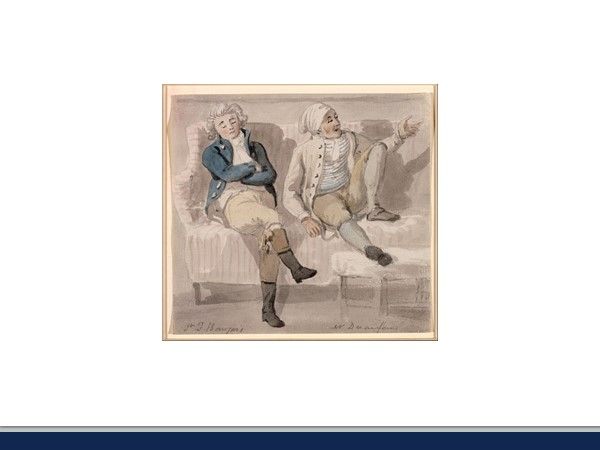

In Desenfans v Vandergucht, Noel Desenfans (one of the founders of the Dulwich Picture Gallery) successfully sued Benjamin Vandergucht, a well known art dealer, for the return of the price (£700) paid for a painting attributed to Nicolas Poussin (1594-1665), the great painter in the classical French Baroque style. Distinguished expert witnesses were called, including (for Desenfans) Thomas Gainsborough, cross-examination of whom led to a somewhat sphinx like opinion on the subject of the legal profession:

Gainsborough: ‘It is so deficient in harmony, taste, ease and elegance that if I had seen it in a broker’s shop, and could have bought it for five shillings, I should not have done it.’

Mr Garrow (he of the BBC’s Garrow’s Law): ‘Do you not think there is something necessary besides the eye, to regulate an artist’s opinion, respecting a picture?’

Gainsborough: ‘I believe the veracity and integrity of a painter’s eye, is at least equal to that of a pleader’s tongue.’

The General Evening Post of Friday 12 June 1787 reported: ‘Witnesses were called to give evidence – what evidence? Not the whole truth and nothing but the truth, for none of them knew anything of the matter. They gave no evidence, properly speaking, but an opinion, and the jury very justly took that opinion which was most probable or rather most generally agreed upon.’

This gives a taste of a common issue in the attribution cases which have succeeded Desenfans v Vandergucht. The date, authorship and origin of a work is very often a matter only of opinion. For rather obvious reasons cases in which provenance and authorship are reliably documented are unlikely to give rise to attribution disputes. So, the cases often concern the question of whether and how a seller or auction house can be made liable for a misattribution when at bottom all that is being provided is an opinion. In Jendwine v Slade (1797), a case of alleged breach of warranty in relation to paintings attributed in an auction catalogue to David Teniers (Flemish, 1610-1690) and Claude Lorrain (French, 1600-1682), Lord Kenyon said: ‘It was impossible to make this the case of a warranty… it could only be a matter of opinion whether the picture in question was the work of the artist whose name it bore, or not.’

Attempts have similarly been made to frame sales of allegedly mis-attributed works as sales by description (Sale of Goods Act 1979 s.13(1)) or as subject to statutory conditions of fitness for purpose and merchantable (now satisfactory) quality (s. 14(2), s.14(6) of the same Act). The attempts have almost always failed: Harlingdon and Leinster Enterprises Ltd v Christopher Hull Fine Arts Ltd (1991), concerning a painting allegedly by Gabriele Münter (1887-1962, a German expressionist painter), Drake v Thomas Agnew & Sons Ltd (2002), involving an alleged Van Dyck (Flemish, 1599-1641) – the problem for claimant buyers, absent an explicit warranty or fraud, being broadly the same, that a seller’s attribution is essentially an expression of opinion about something inherently uncertain.

Claims against auctioneers have generally fared little better, whether by buyers claiming negligent attribution in breach of a duty of care (Thomson v Christie’s), or by sellers who have seen their former possession sold or valued at a much higher amount and claimed negligent miscataloguing: Luxmoore May v Messenger May Baverstock (1990), concerning paintings later sold as a genuine Stubbs; Coleridge v Sotheby’s (2012), alleging the misdating of a ceremonial gold chain of office; Thwaytes v Sotheby’s (2014), the Caravaggio case). The lesson from all these cases is again that, absent an effective warranty (or fraud), misattribution claims are perilous. But warranty claims have been successful: De Balkany v Christie Manson & Woods (1997), concerning a painting catalogued as the work of Egon Schiele (1890-1918, the famous Austrian Expressionist painter); Avrora Fine Art Investments Ltd v Christie Manson & Woods (2012), involving a painting allegedly by Boris Kustodiev (1878-1927, Russian); Sotheby’s v Weiss (2019), in which Sotheby’s were held to have acted reasonably in accepting the rescission of a painting said to be a counterfeit of the work of Franz Hals (1582-1666, the famous Dutch Golden Age painter).

Through all these cases the stories and characters behind them have continued to fascinate and charm in themselves.

The main questions in Thomson v Christie’s (the Houghton Urns case) were whether the Urns were manufactured in the 18th or 19th Century (the difference in value and likely hammer price was massive) and whether Christie’s was negligent in cataloguing them as 18th Century. Evidence came from many experts – including on the 18th Century methods of manufacture of gilt bronze and porphyry decorative items (from Fernando Moreira, the former chief restorer at Versailles; and the well named Professor del Bufalo, on the porphyry), metallurgists (including on the nuclear half-life of the metal in the Urns) and auction practice. Professor del Bufalo explained that the porphyry from which the bowls had been made can only have originated from an isolated site in eastern Egypt, whence it would have been mined by the Romans, transported to Rome, and turned into columns in the Forum and elsewhere. In the 18th Century porphyry columns were to be found lying around Rome, available to be taken and shipped to other European centres – thus the porphyry’s arrival in Paris, where it will have been laboriously carved into the resulting shape of the bowls in the Urns. This is not information one comes across every day.

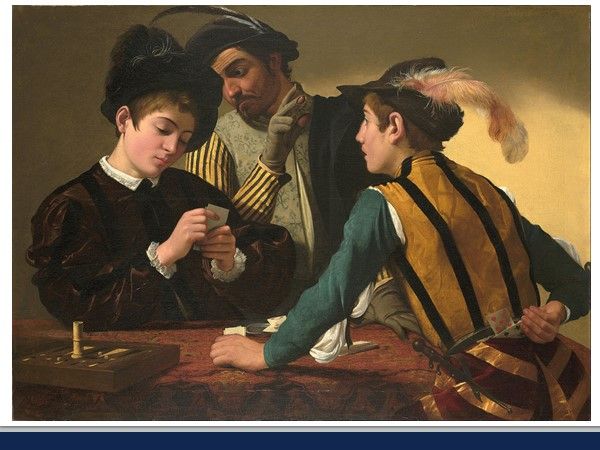

The Caravaggio case (Thwaytes v Sotheby’s) had quirky features of a different kind. Mr Thwaytes had inherited a number of paintings from his father’s cousin Surgeon Captain Thwaytes. In 1947, the Surgeon Captain paid an antique dealer in Kendal £100 for a picture of four scantily clad young men with some grapes and musical instruments. Within five years, the painting had been universally accepted by scholars as Caravaggio’s famous lost painting known as The Musicians or The Musical Party, a painting commissioned by Caravaggio’s first great patron Cardinal Del Monte in Rome in or around 1595, and subsequently passing through the collection of no less a figure than Cardinal Richelieu. No-one seems to know how or when it found its way to the Lake District, but these things do happen and that’s where it stayed until it was snapped up by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1952, for a price in the region of £50,000. The same year, an article dedicated to the picture appeared in The Burlington Magazine written by the 42-year-old Denis Mahon, the distinguished art historian. Afterwards it became something of a hobby for Surgeon Captain Thwaytes to collect paintings with Caravaggio connections including three copies of another well-known missing painting, also from Caravaggio’s early years in Rome, The Cardsharps, the subject of the 2014 litigation. The acknowledged original version of the Cardsharps also painted for Cardinal del Monte, now in the Kimbell Art Museum in Texas having been rediscovered in a restorer’s studio in Zurich in 1987 after being lost for almost a century.

The judgment of Mrs Justice Rose tells the rest of the story. Mr Thwaytes consigned one of his versions of The Cardsharps for auction. Sotheby’s catalogued it as a copy, and it sold for £42,000. The buyer was (the now Sir) Denis Mahon. On his 97th birthday he unveiled his (now cleaned) purchase as – he asserted – a second original version of The Cardsharps, by Caravaggio himself. Litigation followed… you can read the full tale of the trial in Caravaggio’s Cardsharps on Trial (2020), by Professor Richard Spear, Sotheby’s expert witness at the trial.

I cannot finish this article without paying tribute to the late Richard Edwards QC, my friend, former pupil, longstanding Chambers colleague (and junior in the Thwaytes case), and Middle Temple member. Richard died suddenly in January 2021, aged only 54. He was an outstanding barrister, perhaps best known for his many art cases. He was also a lovely man, who is very much missed.

This article is based on a Sherrard Conversation talk last December, which Master Onslow gave with the late Richard Edwards QC.

Master Andrew Onslow is a member of Chambers at 3 Verulam Buildings in Gray’s Inn. He has a commercial practice, with a recognised specialism in cases involving works of art and cultural property. He is a member of PAIAM (Professional Advisers to the International Art Market), a CAfA (Court of Arbitration for Art) Arbitrator and a regular speaker at art law events.