In 2010, a North Carolina jury awarded Cynthia Shackelford a $9 million verdict of actual and punitive damages against Anne Lundquist for alienation of the affection of Shackelford’s husband, Allan. The verdict was upheld on appeal. Similarly, in Hutelmyer v. Cox the North Carolina Court of Appeals approved a $1 million verdict, including $500,000. in punitive damages in favour of a wife against her husband’s secretary for alienation of affection and criminal conversation. These awards are part of a larger trend. There have been several other seven-figure results, although the majority of awards are of much smaller amounts.

While whopping verdicts are certainly eye catching, perhaps the greatest significance in these reports is that such judgments are not uncommon in North Carolina. One attorney estimates that overall, North Carolina sees approximately 200 new alienation of affections cases each year. As of 2016 in the United States, only North Carolina continues to recognise both alienation of affection and criminal conversation as valid tort claims. As a result, North Carolina remains virtually the only place in which heart balm suits (typically, alienation of affection claims) could be described as common enough to have developed a substantial body of modern case law.

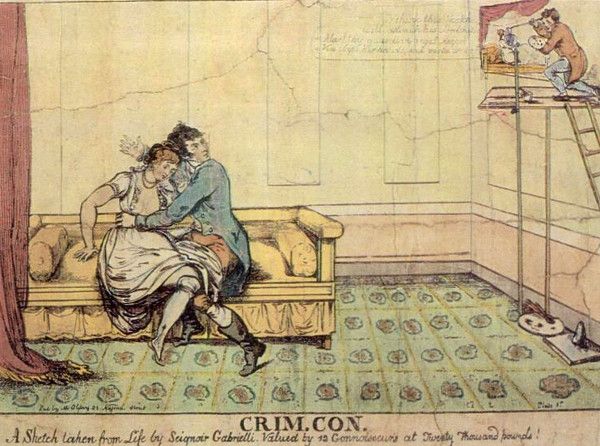

As balm for a broken heart, both alienation of affection and criminal conversation are English common law torts. However, in the United Kingdom, the torts grew into disfavour, and by 1857, criminal conversation was abolished. Both torts have now been extinct in England for all practical purposes for over a century.

Criminal conversation is ancient, with roots beyond the common law, in the ancient customs and traditions of primitive European tribes. The early customs and traditions of the European tribes could result in quite brutal and often public punishments. Among the Teutonic tribes, for example, adultery was punished severely. The husband was permitted ‘to cut off the hair of the guilty wife, and having assembled her relations, expel her naked from his house, pursuing her with stripes [i.e. lashes] through the village.’ Additionally, some tribes permitted the husband to kill the lover if he found him in the act of adultery with his wife. Later, penalties were lessened; the husband was merely permitted to emasculate the adulterer, collect a monetary penalty and select a new wife.

Money damages evolved to be a substitute for the right of the husband ‘publicly and physically [to] punish the offending parties and/or obtain a new wife.’ As the common law matured, recognition of the concept tied to the protection of the husband’s legal interest in maintaining a pure line of descent for the purposes of inheritance. When the hierarchy of the Catholic church began to replace the structure of European tribal and feudal societies, moral reasons for discouraging adultery were superimposed, the custom of acquiring a new wife was disregarded, and the remedy of damages, now unliquidated, emerged in the form of the action for criminal conversation.

Ecclesiastical Courts had ‘exclusive jurisdiction over all matters relating to the marital relationships and these courts could only administer social punishment. For the husband to obtain monetary damages, he had to bring his case in the Royal Courts under the established writs of abduction or ravishment. Under these writs, the wife was property; ‘[w]hen a man trespassed on another man’s wife, the adulterer was obliged to pay damages for the injury as if he had taken the plaintiff’s livestock or gone uninvited onto the plaintiff’s land.’

Abduction and ravishment were a legal fiction, construed as the cuckolding paramour kidnaping the wife and robbing the husband, even when the underlying actions were consensual sex between the wife and paramour.

By the 17th Century, the law of master and servant created some nuances in the analysis of infidelity as a civil action. Under these new theories, ‘a party would be held civilly liable for “enticing” away a servant from the master or physically injuring the servant, leading to a loss of services. Just as the interference with the services of a servant was deemed to be a trespass, so too the interference with a husband’s relationship with his chattel spouse was actionable against a third party. Thus, the property right of a husband in his wife gave rise to a cause of action when a third party ‘abducted her, seduced her, or “stole” her affections.’ Under the law of master and servant, the idea of the husband’s property right in his wife led directly to the concept of his property right to her exclusive ‘services.’

This legal shift also led to the development of a distinct action for enticement, which included action when no adultery took place. The now-obsolete common law cause of action for enticement, could be maintained by a husband when a third party acted purposefully to disrupt the marital relationship or used force to separate the wife from her spouse. Over the years, enticement evolved into the more familiar tort of alienation of affection.

By the time of Blackstone’s famous Commentaries, the actions were well known in English common law. On the other side of the Atlantic, the United States inherited the English common-law system, incorporating the English rationales for torts. These torts made their way into the law of North Carolina, which first recognized alienation of affection in Barbee v. Armstead, 32 N.C. 530, 51 Am. Dec. 404 (1849).

Christianity, both Catholic and Protestant, charged Eve with bringing sin into the world and demanded women’s subordination. In British America married women lost control of their property and, by implication, lost many other rights under the principle of coverture, which maintained that a woman’s husband legally covered her so that she had no independent legal standing.

At the turn of the 20th Century, a uniquely American twist emerged. With the enactment of the Married Women’s Property Acts, women received an equal right to bring both actions. Thus, in the modern North Carolina version of the torts, each spouse is now considered as the chattel of the other, laying legal fiction atop legal fiction to maintain the actions.

Allowing women to sue for alienation of affections, criminal conversation, or their own seduction undermined the traditional justifications for these torts. Although these torts could, by the 20th Century, be invoked by women, that did not make them any more egalitarian, progressive, or otherwise indicative of gender equality. The growth of women’s rights nationally, as part of an increasing public interest in social justice, led to a decline in the prevalence of the heart balm torts. As in England in the 19th Century, they grew into disfavour in the States. However, with a new legal justification, arguably tied to southern evangelical mores of preserving marital harmony through strict punishment, in some places these torts took on the new role as guardians of marriage as an institution.

So, they remain, despite a quarter century of activity by both the Bench and Bar of North Carolina to do away with them. The North Carolina General Assembly has proven unable, despite multiple attempts, to do more than narrow the statute of limitations for these torts. The North Carolina Court of Appeals attempted to declare them obsolete and abolished. The North Carolina Supreme Court swiftly reminded the Court of Appeals of its place:

It is appearing that the panel of Judges of the Court of Appeals to which this case was assigned has acted under a misapprehension of its authority to overrule decisions of the Supreme Court of North Carolina and its responsibility to follow those decisions, until otherwise ordered by the Supreme Court.

It is therefore ordered that the petition for discretionary review is allowed for the sole purpose of vacating the decision of the Court of Appeals purporting to abolish the causes of action for Alienation of Affections and Criminal Conversation.

To make a prima facie case for alienation of affections in North Carolina a plaintiff must show that:

(1) The plaintiff and his spouse were happily married with genuine love and affection;

(2) The love and affection was alienated and destroyed; and

(3) The defendant acted wrongfully and maliciously to cause the loss of love and affection.

The tort does not even require sexual activity on the part of the defendant and, with some limited exceptions, a plaintiff can bring an action for alienation of affection against other third parties who merely proffer advice that contributes to the harm or dissolution of the marriage. Further, the plaintiff does not have to prove an untroubled marriage, only that ’some love or affection’ existed within the coverture and that it was ‘lost as a result of the defendant’s wrongdoing’. In other words, the wrongful and malicious conduct of the defendant need not be the sole cause of the alienation of affections. It matters not that the adulterous spouse consented to the tortious activity. Surprisingly, in North Carolina a defendant can be held liable even if he or she was unaware of the marital status between the plaintiff and spouse.

Criminal conversation is close to a strict liability tort. Recovery is allowed upon proof of a valid marriage between the plaintiff and spouse and an act of adultery between the defendant and the plaintiff’s spouse during the marriage. The only defence, other than the statute of limitations, is the consent of the plaintiff. Historically, even the consent of the wife to her own actions was not a defence: as the legal inferior of her husband, the wife could not consent to the injury of her superior. Adulterous sexual intercourse is the crux of the claim.

The actual element of sexual intercourse in criminal conversation is rarely proved by direct evidence. Instead, under North Carolina law, the element can be presumed from the circumstances. When attempting to prove sexual intercourse by circumstantial evidence, plaintiffs can use the ‘opportunity and inclination doctrine’ in North Carolina, which presumes adultery when two conditions are proved. First, the plaintiff must prove an adulterous disposition or inclination of the parties. Second, the plaintiff must prove that there was an opportunity created to satisfy the parties’ mutual adulterous inclinations.

Although the causes of action are historically distinguishable, in their modern application ‘they are substantially alike in their public and private functions’ in that they both purport ‘to deter marital interference and to promote marital harmony’ by compensating judicially for private injury. Indeed, the two causes of action are so interdependent and connected, that, when tried together, the jury should consider only one award for damages: to compensate the plaintiff for the loss of consortium of the alienated or despoiled spouse.

Originally, at the common law in North Carolina consortium was understood to mean ‘a bundle of the husband’s legal rights to the services, society and sexual intercourse of his wife.’ Later, when the proprietary and service-related basis of the action for loss of consortium came into conflict with changes in the legal status of women, the concept of consortium was broadened to include a fourth element of ‘conjugal affection,’ with a somewhat lessened emphasis on the notion of the property right to ‘services.’

A renewed attempt to abolish the torts in the 2021 North Carolina General Assembly legislative session seems to have stalled. The failure to advance the legislation comes despite the salacious allegations in and Raleigh tongue wagging over Arthur Johns’ 2020 lawsuit against the then Republican State Senate Whip, Rick Gunn, for alienating his wife’s affections. If the General Assembly is unmoved by one of their own colleagues becoming a party to such an action, it seems highly unlikely that any legislative fix will be forthcoming in the current political climate.

There is one jurisdiction within the boundaries of North Carolina in which the heart balm torts are not recognized: the Qualla Boundary, the territory of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians. In the case of Rosario v. Arneach, 5 Cher. Rep. 10, 2006 WL 6500567 (2006), the Tribal Court held that, as a matrilineal society, Cherokee women were never considered the property of their husbands. Applying Cherokee culture and tradition as the organic law of the Tribe, the Court found that alienation of affection and criminal conversation could not be maintained in that jurisdiction as there was no historical basis for the torts.

On similar grounds, the Supreme Court of the U.S. Virgin Islands recently rejected an attempt to recognize the heart balm torts. Thus, not only are American courts abandoning the torts, those who have not considered it before are declining to adopt it.

Nonetheless the common law lives. The question remains, what does it take for obsolete portions of it to die? Someday, perhaps, North Carolina will have an answer.

Judge J. Matthew Martin is the first American Bar Association Tribal Court Fellow. He received a Ph.D. in Judicial Studies from the University of Nevada and his JD from the UNC School of Law. His book, The Cherokee Supreme Court: 1823-1835, was published in 2020 by Carolina Academic Press.