The art of handwriting is something which most of us have possessed since being taught in our early years. Recently, the use of handwriting has declined, with documents, letters and more being typed and shared on computers, although many of us still make handwritten notes and the skill still holds much value.

The earliest recorded handwriting to be discovered comes from the Mesopotamian City of Uruk, in modern-day Iraq, and dates from the end of the 4th Millennium BCE. Prior to this, oral tradition had been the predominant means of sharing information with others. Over time, different societies formed their own scripts and letters, which constantly evolved and transformed over the centuries towards the various scripts which we use today.

The Middle Temple Archive holds an abundance of records containing handwriting, spanning over five hundred years, from 1501 to the present day. In this article, we look at how handwriting has evolved and changed as reflected in the Inn’s records, as well as AI technology used to read handwriting, and the fascination with famous hands and signatures.

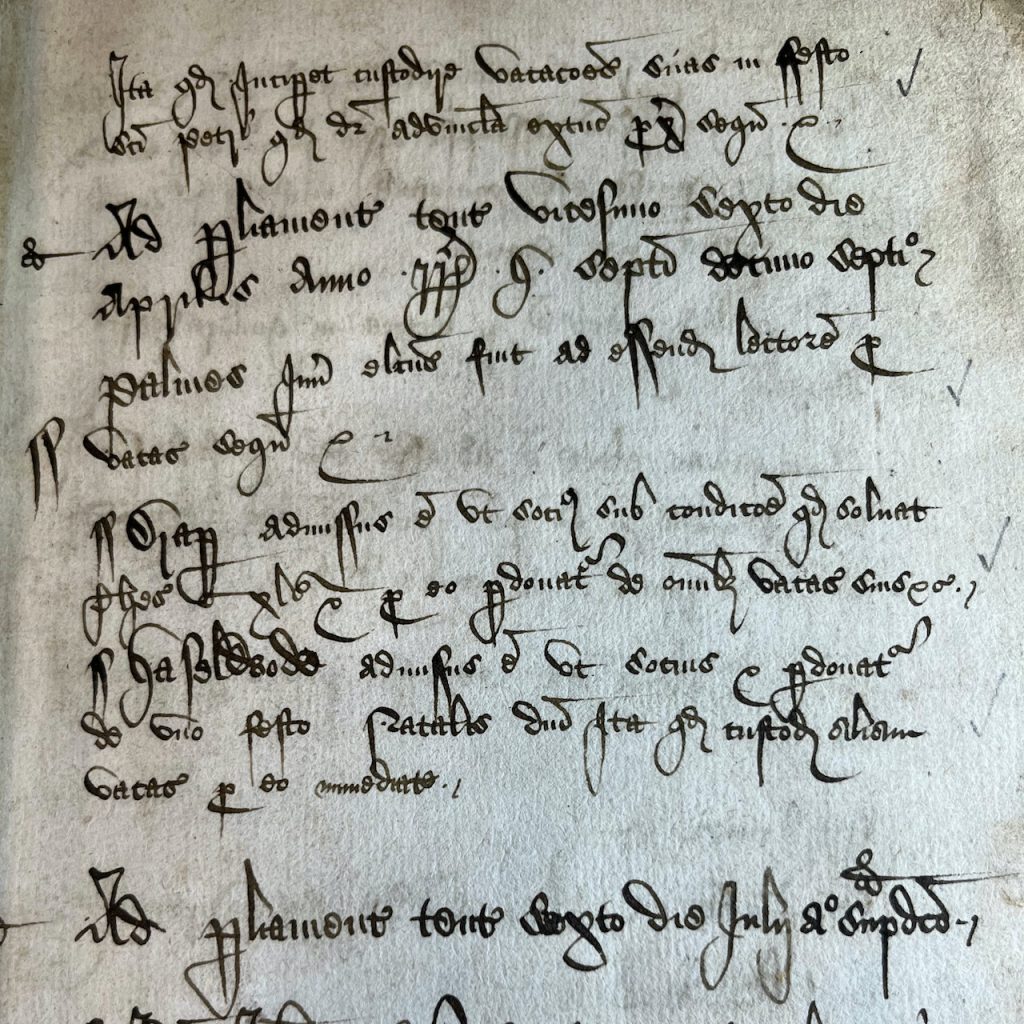

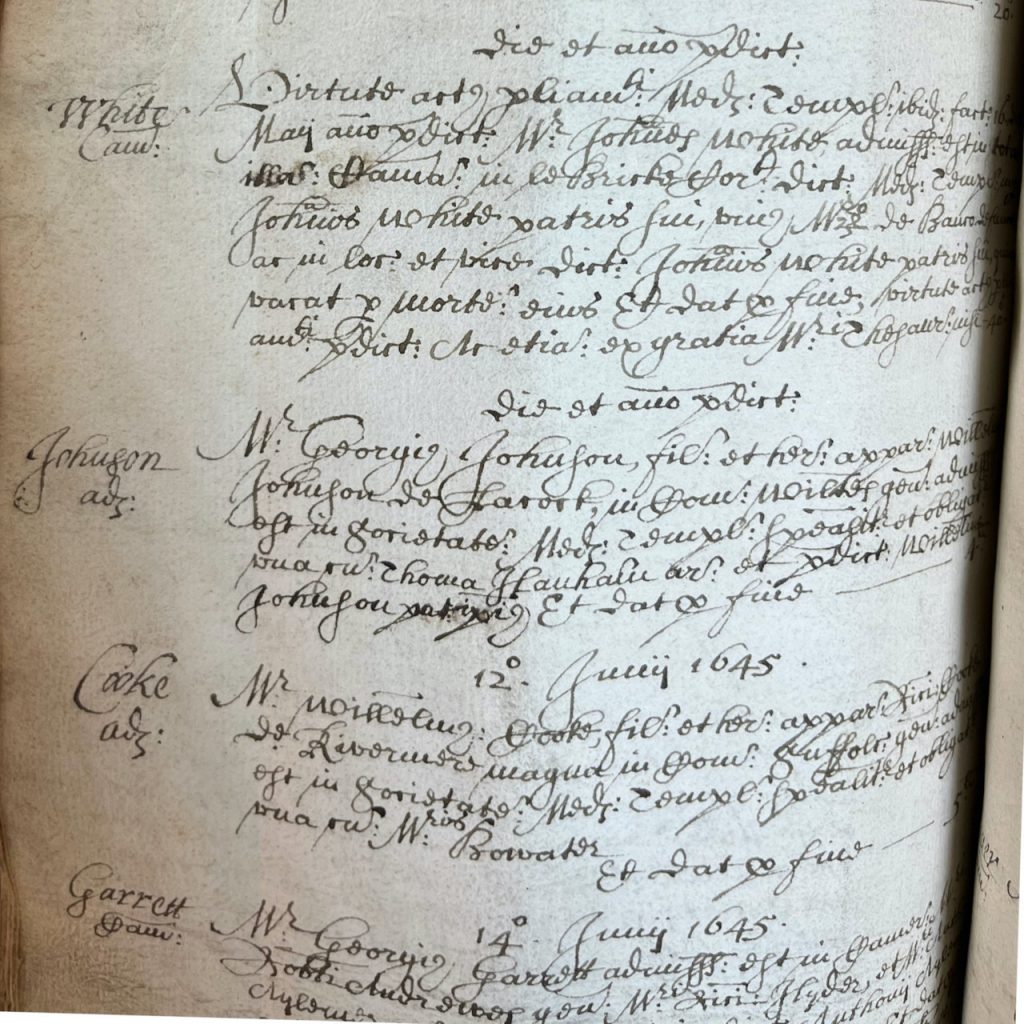

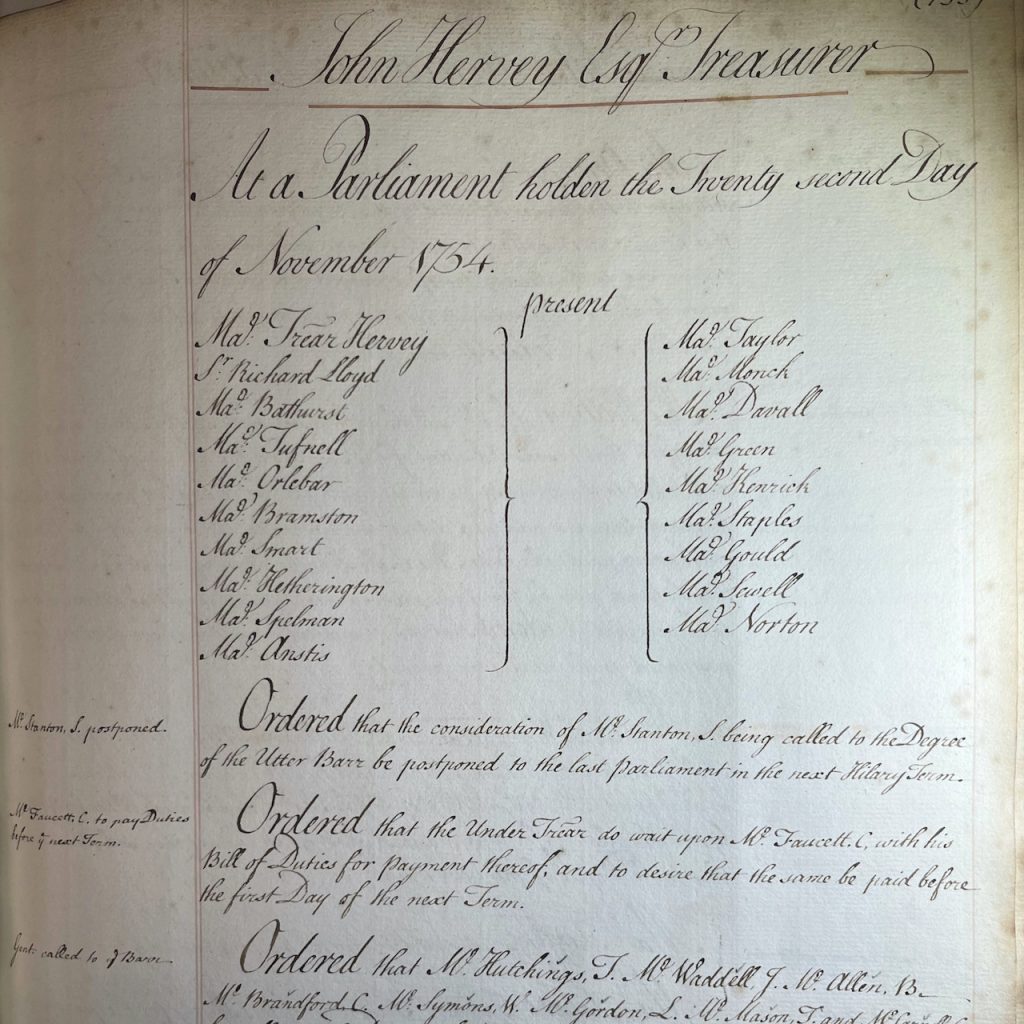

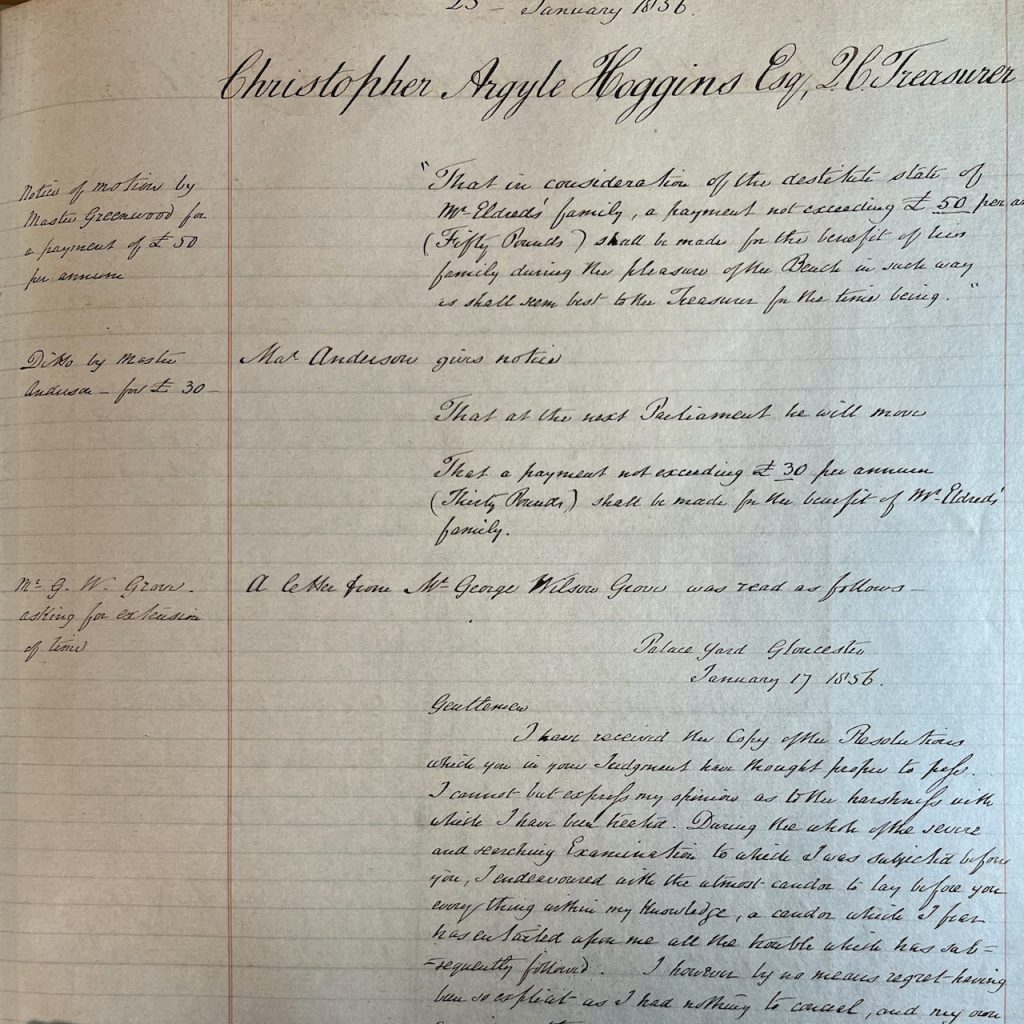

Historically, many of the Inn’s official records (such as the Minutes of Parliament, the records of the Middle Temple’s senior governing body) were written in Latin. The Minutes of Parliament – a series of records still being produced today – serve as an excellent example of showing how handwriting changed from 1501 through to 1968, at which point the Minutes began to be typed.

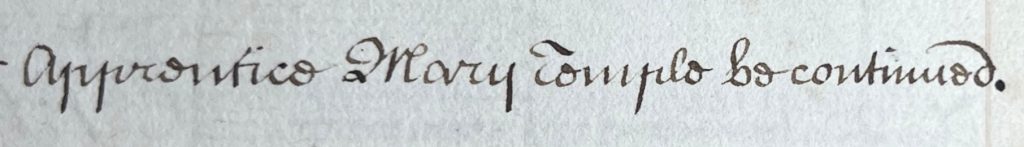

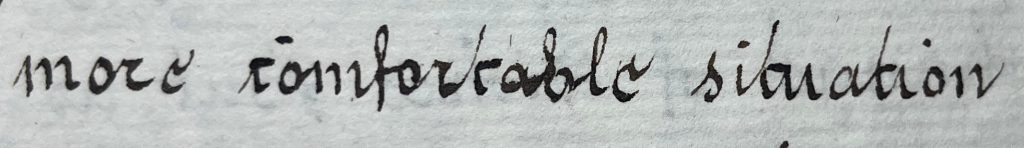

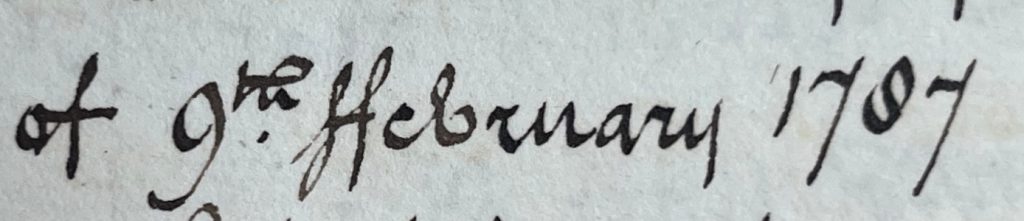

These four images show the transisition of handwriting in the Inn’s Minutes dating from the 16th, 17th , 18th and 19th Centuries. One can clearly see the evolution not just of the hand and letter shapes, but also in the paper and ink used.

The art or science of reading handwriting dating from earlier historical periods is known as palaeography, concerned with the forms and process of writing, rather than the actual contents. Within the Inn’s collection, there are thousands of documents such as letters, minutes, orders, reports, and bills written in English which require palaeography skills to decipher the text. Whilst most English alphabet letters have retained a similar form over the centuries, certain letters within historical records can prove to be something of a headache for those endeavouring to read them.

One example of this is the letter ‘e’, which can take many different forms depending on the handwriting. One common form it took was to be written looking more like an ‘o’. As one can see in this example below, which reads ‘apprentice Mary Temple be continued’, the ‘e’ could very easily be mistaken for an ‘o’.

Another letter that can trouble a modern reader is the letter ‘c’. When written in historic documents, in its lowercase form, it is often mistaken for either a ‘t’ or an ‘r’. The text below reads ‘more comfortable situation’, however the ‘c’ at the start of ‘comfortable’ could well be another letter to the untrained eye.

Another example of changing hands is the capital letter ‘F’. Prior to 1700, the capital ‘F’ was almost always represented by a double ‘f’, with the ‘F’ we know today only coming in with the introduction of italic form handwriting. However, as you can see from the example below, many people continued to use the double ‘f’ as a capitalisation. The text reads ‘of 9th February 1787’.

Reading these words and transcribing them into legible text is a highly specialised skill and requires a good eye for detail. However, humans are no longer the only ones who can read and decipher this handwriting.

As artificial intelligence technology has evolved, systems have been developed which can read and transcribe handwriting from different time periods. One such piece of software which specialises in this, which is being used by the Middle Temple Archive, is Transkribus. This programme is an ‘AI-powered platform for text recognition, transcription and searching of historical document’. By using Transkribus, we are able to ‘teach’ a machine to ‘read’ a digitised version of our historical documents, with the machine then able to create a typed text version of the words, which can be edited and converted into a pdf document. Transkribus is able to transcribe it to a high degree of accuracy – at the moment, for every 100 words processed, roughly 96 of them will be transcribed correctly, and this rate is always improving.

We are working to process the Inn’s Minutes of Parliament using this technology, and hope that by creating electronically searchable digital copies of some of our key records, we will provide greatly enhanced and more efficient access, for the team and for researchers, to the information and knowledge contained within these documents.

Even as we move towards the majority of records and documents being produced electronically as typed text, there is nonetheless still a demand for and interest in handwritten text. One case where this is most apparent is that of signatures and autographs of celebrities and notable historic figures.

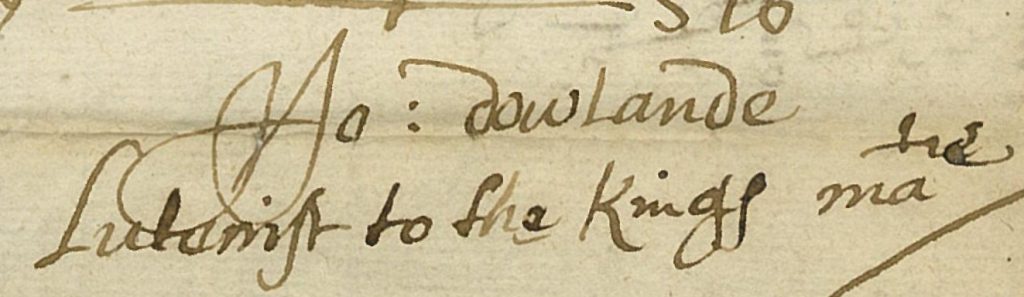

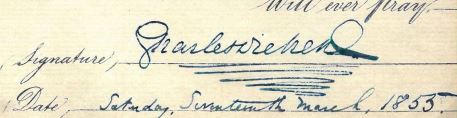

Thanks to the extensive number of notable members of the Inn over the past five or more centuries, the archive is full of many famous signatures, with autographs ranging from those of John Dowland to Charles Dickens, and King James I to the Queen Mother.

It is thought that the earliest known autograph collection was compiled in 1466, beginning a trend which would be followed by many, establishing collections containing primarily the signatures of friends and acquaintances, to show off who a collector knew. By the 17th Century, collecting autographs and manuscripts for the sole purpose of historical passion and interest was becoming more popular amongst the great antiquaries of the age. Two particularly prominent antiquaries were also members of the Middle Temple – John Evelyn and Elias Ashmole.

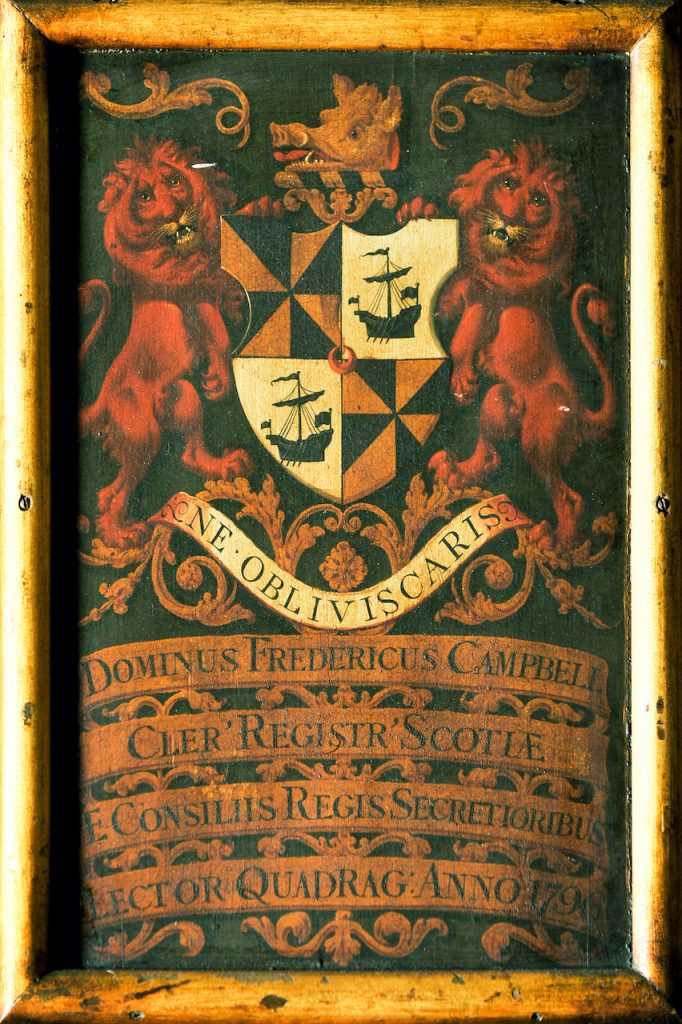

Another notable collector of autographs and signatures was Lord Frederick Campbell, who also served as Lent Reader in 1796 and Treasurer in 1803. Campbell transferred a collection which is now known as ‘The Campbell Charters’ to the British Library. This collection contains the oldest surviving seal of an English King, that of Edward the Confessor – before the advent of signatures, a wax seal was often used to authenticate a document. Campbell also gave to the British Museum what is the earliest known royal autograph to exist, that of King William Rufus, c.1090, which is a cross in the centre of a document in which he (King Rufus) gave the manor of Lambeth to the Church of Rochester.

The signatures of Middle Templars have also been an important part of many notable historic documents. For example, five of the signatories to the US Declaration of Independence were Middle Templars: Edward Rutledge, Thomas Heyward, Thomas McKean, Thomas Lynch, and Arthur Middleton.

Although, as technology evolves, we turn more and more towards word processed text and away from handwriting, there is still an importance placed upon existing handwritten material, and handwriting undeniably gives a document a greater sense of the human and the personal.

Francesca qualified as an archivist at the University of Glasgow in 2019, joining the Inn’s Archive Department later that year as Project Archivist, progressing to Assistant Archivist in 2021. She works on a variety of different projects, including the preservation of the Inn’s digital records.