When a barrister was droning on in court, Judge Percy Harris provided the public with some much-needed levity by starting a one-sided game of table tennis.

If he considered a counsel’s legal argument to be irrelevant or lacking concision, the Circuit Judge would brandish a yellow table tennis bat to warn them to hurry up. Those who failed to show the requisite alacrity were shown another bat, coloured red. The offending barrister, whose face might now be as red as the bat, knew then that the florid sentence they were in the midst of constructing must be their last. Many appreciated this legal semaphore, which Harris had devised as a response to a direction from the Lord Chancellor’s office for judges to exert more control over lawyers who wasted court time with long-winded speeches.

Private Eye, riffing on his record as a decorated wartime seaman who had helped to sink two U-boats, dubbed him ‘Bomber Harris’. The judge’s last recourse was a copy of The Times. Private Eye reported in March 1995 that ‘in the unlikely event that the advocate still fails to take the hint, he or she is shown a copy of the relevant Times law report spelling out that barristers or solicitors who unjustifiably impinge upon court time may be required to foot the bill personally for wasted costs’.

Harris’s retirement from the Bar soon afterwards prompted considerable relief from many counsel who had been eviscerated by the man with a reputation as one of the most irascible Circuit Judges. Young barristers, and even old ones, dreaded approaching the bench where the granite-faced Harris leant forward with a thunderous stare and browbeat the bores of the Bar.

It could be argued that Harris was a relic of a bygone age. In 1992 he caused national headlines by insisting that a Rastafarian man ‘remove his hat’ in court. Innocent of the fact that the colourful woollen headwear was an article of faith in the same way that it would be for a Sikh man, Harris was unsympathetic and unbending after he had been enlightened.

The sense of outrage was hardly assuaged by the fact that the man was the partner of a plaintiff who claimed that her son was being discriminated against by teachers at his school in Wandsworth, southwest London, on account of his colour — the first case to use the race relations law to contest the right of heads and governors to exclude pupils. Harris did not object to the plaintiff wearing headwear but ordered her partner, Patrick Abrahams, to remove his. After an adjournment, during which the Society of Black Lawyers applied to the Lord Chancellor to have Harris removed from the case, the judge backed down but not before adding (some thought ungraciously) that he had been ‘pushed into it’ and viewed the matter as ‘entirely trivial’.

‘I did not know that anyone was a Rastafarian, whatever a Rastafarian is,’ said Harris. ‘I find it difficult to understand why the man cannot take off his hat.’

Standing broadly at 6ft 1in, Harris was a war hero who won the Distinguished Service Cross for gallantry. He had interrupted his law degree at Pembroke College, Cambridge, in 1943 to enlist in the navy as a midshipman.

Attaining the rank of sub-lieutenant, he was involved in escorting several Allied shipping convoys to the Soviet Union in the treacherous icy waters and at great risk from U-boats being launched from Nazi-occupied Norway.

On January 27, 1945, while serving in the frigate HMS Keats, he was involved in operations that led to the sinking of U-boat 1051 in the Irish Sea. While the convoy was re-forming into two columns, another submarine, U-1172, having manoeuvred itself between them, attacked on the eastern side and sank three vessels. Keats was patrolling on the western extremity of the search plan when the 19-year-old Harris obtained a good contact using Asdic equipment, with which he was unfamiliar. The U-boat was attacked with a ‘Hedgehog’ anti-submarine weapon that comprised 24 mortar bombs launched into the air that would detonate on contact with a hard surface under the sea. U-1172 was sunk. Harris’s commendation noted that he ‘displayed outstanding efficiency and devotion to duty, remaining smartly at his post on and off for 36 hours’. The captain of Keats added: ‘This officer showed coolness and courage, although this was his first patrol being a temporary relief for the ship’s Asdic officer.’

When in 1995 Harris retired from the Bench, he was one of the last surviving silks to have been decorated for valour for their service in the Second World War, notable others being Lord Justice Sir Tasker Watkins VC, Lord Griffith MC and The Hon Sir John Wood MC.

Cutting a more whimsical figure in his plus-fours, Harris kept in touch with many of his old wartime comrades on the golf course.

An accomplished knitter, he made brightly coloured pom-poms that he would attach to his tees to ensure that he did not lose them. Pom-poms would be pressed upon his friends and associates at the Bar Golfing Society. He served as hon secretary of that society from 1957 to 1967, cofounded the Circuit Judges Golf Society and founded the Templeman-Chetwood Bowl, contested between barrister and solicitor members at Woking golf club, where the Private Eye article remained on the noticeboard.

On one of his favourite courses at Royal St George’s, in Sandwich, Kent, he was competitive with a handicap that hovered around seven. Harris won the annual Bar tournament in 1960, 1965 and 1969, but his main motivation was fellowship with his fellow barristers, whom he would regale with off-colour stories — some of which he regarded as being for male ears only.

Retirement had not mellowed his old-fashioned perspective on life. When the Bar Golf Society admitted “lady barristers” in 1992, Harris dropped another bomb, resigning with immediate effect. It was rumoured that he cut his Bar Golf Society tie in half. What is certain is that he never reapplied to join.

Yet his days on the course enjoyed a renaissance when with General Ronnie McAlister, who had served with distinction during the Malaya insurgency (1948-50), he founded the Army and Navy Cup at Royal St George’s for veterans of the armed forces who were over 80.

John Percival Harris was born in 1925 to Thomas Harris, a bank manager, and Nora, née May. He was educated at Wells Cathedral School, where he was Head Boy.

After being transferred to the Far East in May 1945 as part of a naval task force to reoccupy Hong Kong, Harris returned to Pembroke College in 1946 and graduated three years later.

He was Called to Middle Temple in 1949, where he obtained a seat as a pupil of Douglas Lowe in the chambers of Gerald Gardner QC.

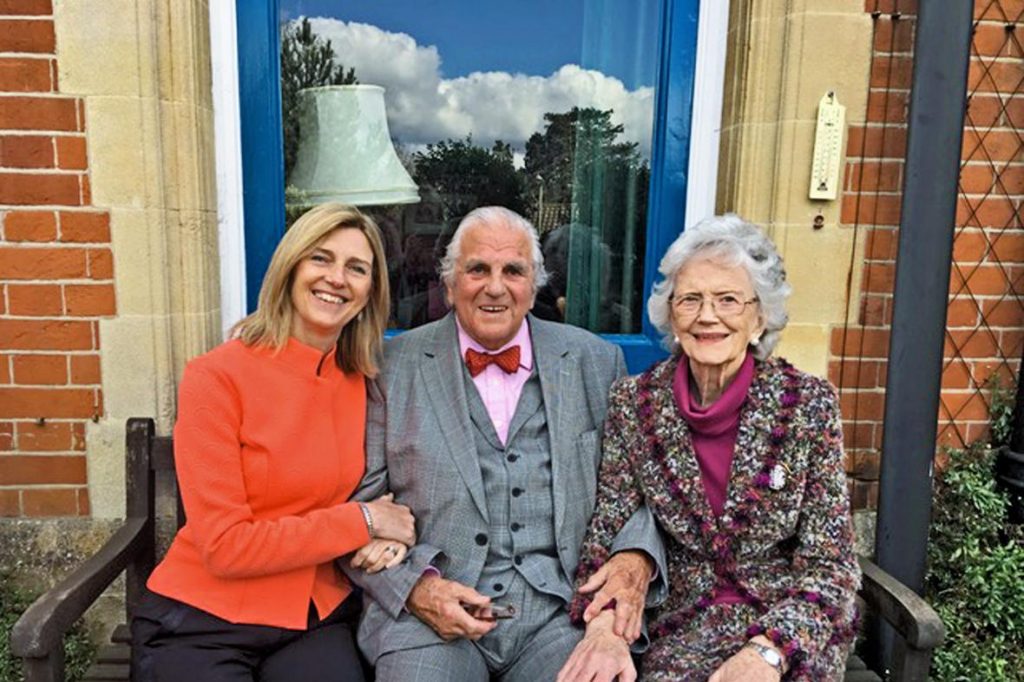

In 1959 he married Janet Douglas, whom he met at a drinks party. She survives him, along with their two daughters and a son: Juliet is a headhunter, Charlotte a marketing consultant and Steven an accountant.

Harris’s most notable case as a junior counsel was acting for 62 claimants against Distillers Biochemicals Ltd relating to the drug thalidomide, which had been prescribed to pregnant women suffering from morning sickness, causing birth deformities in some 10,000 people worldwide. Harris lasted the course of an exhaustive five-year litigation led first by Gerald Gardner QC, then by Desmond Ackner QC and finally by John Stocker QC. Distillers resisted all the way, but finally settled in 1968 and its compensation scheme was greatly expanded after an investigation by the Sunday Times Insight team.

Two years after the Distillers settlement, Harris took silk and was made a Bencher of the Middle Temple. He served as a Recorder of the CrownCourt from 1972 to 1980, when he was appointed as a Circuit Judge.

In 1988 he ordered David Shaw, a Conservative MP, to pay £180 in damages and costs for assaulting a female photographer from Today newspaper, which had branded him ‘the vilest MP in Britain’. Debbie Brady had tried to take his picture after it had emerged that Shaw had taken on an unpaid researcher, the model Pamella Bordes, who had also been exposed as a ‘high-class courtesan’.

In his judgment at Westminster Crown Court Harris said that in trying to wrest the camera out of Brady’s hands Shaw had ‘acted like a child fighting for his favourite toy’ and that his defence was ‘far-fetched and specious’. He added that Shaw should have apologised to Brady, bought her a bunch of flowers or made a donation to her favourite charity. ‘Instead he chose to fight this action at a great deal of expense to everyone.’

After retiring as a Circuit Judge in 1995 Harris remained as a Senior Bencher at Middle Temple and sat as a Deputy Judge at the Sovereign Base Area in Cyprus until 2000.

A keen cook and collector of Victorian art, he continued to play golf into his nineties, often staying at his house in Sandwich, handily placed for a round at Royal St George’s.

Harris had one final run-in with the Lord Chancellor’s office after he qualified to appear on the BBC programme Mastermind: his chosen specialist subject was not table tennis but Victorian art. The Lord Chancellor told him that it would be inappropriate for a sitting judge to make an appearance on the show, however erudite. Whether Bomber Harris was shown a red table tennis bat is unrecorded.

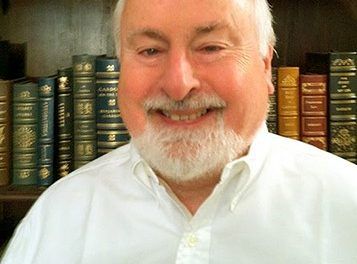

His Honour Percy Harris DSC KC, Circuit Judge, was born on February 16, 1925. He died on September 28, 2022, aged 97

Reproduced with kind permission from The Times