This essay was written by Master John Mitchell shortly before his passing on Saturday 27 March 2021. Intended to be his reading at his Reader’s Feast, it was later edited and read in Master Mitchell’s honour by Master Andrew Hochhauser and Mass Ndow-Njie on Wednesday 23 June 2021.

Throughout his life TMC’s aim was to develop his talents to enable him to play a leading role in his wider Black community. This was in part an ambition to achieve his own potential as a man, equal to all men- but also as great an ambition for all members of his community. As he repeatedly emphasised, a primary tool in achieving them was education. In the year, he was Called and three years after the abolition of slavery in the United States he addressed students at his former school in Pennsylvania:

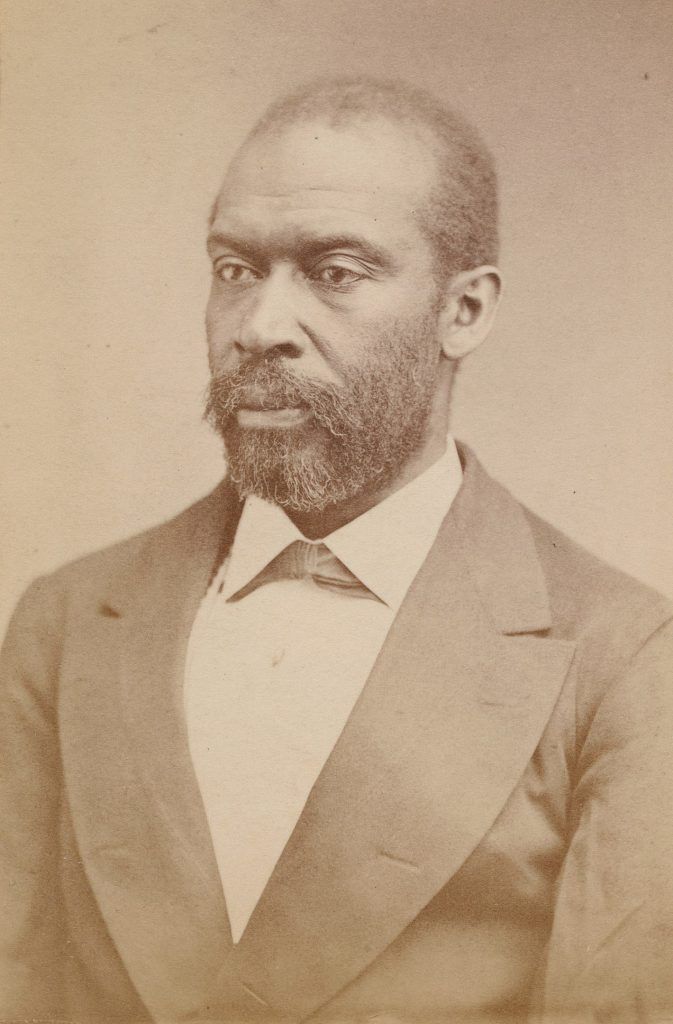

Thomas Morris Chester (TMC) who was Called to the Bar by the Middle Temple on the Saturday 30 April 1870 was probably the first African American to become an English barrister. This however was only one and perhaps not the greatest of his achievements. By 1870 he was 34 years old and had been an activist and advocate for Black rights since his teens, an educationalist in Liberia, its roving plenipotentiary in Europe and a newspaper war correspondent in the US Civil War.

In a country like [the United States] …which is everywhere recognising merit irrespective of complexion and which by its fundamental law has proclaimed the equality of all men, it especially becomes a people, whose mental improvement circumstances have retarded, to fully appreciate the utility of learning.

Thomas Chester was born in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania on the Sunday 11 May 1834, the fourth of George and Jane Chester’s twelve children. His father owned a restaurant and may have been born a slave. Jane who had certainly been born into slavery in the south escaped to the north via the underground railroad to Pennsylvania in 1825.

Although African Americans in the northern states were free at the time of TMC’s birth they lacked citizenship and were often subjected to both formal and informal segregation. For them the aim was not only securing freedom for the southern slaves but also achieving equality with the white community. However, the issue of where and how this should be manifested divided the community. Those who doubted that equality in the US could be achieved thought that the future lay abroad in countries such as the West African state of Liberia. Their view, known as Colonization (sic), was shared by many white politicians such as Lincoln who notoriously made his views plain when during the Civil War he met a delegation in 1862:

Even when you cease to be slaves, you are yet far removed from being placed on an equality with the white race…. It is better for us both, therefore, to be separated.

Others like TMC’s parents, strongly disagreed believing that their future properly lay in the United States. As one activist put it, why should the US be drained of ‘the most enlightened part of our coloured brethren, so that they may be more able to hold their slaves in bondage and ignorance?’

This issue dominated the first half of TMC’s life. Until his mid-30’s he believed in Colonization, writing that Liberia was ‘the only true and natural home of our race’. And at the age of nineteen and sponsored by the Pennsylvanian Colonization Society he sailed for Liberia for the first time to further his education. However, he quickly returned to the States after finding that the school in which he had enrolled could offer little beyond his existing level of education. But after eighteen months at the Thetford Academy in Virginia during which he studied the classics as well as being an active debater he returned to Liberia, this time as a teacher. This was to be the first of three attempts to settle in Liberia which he made in the next five years.

TMC found life in Liberia was not as trouble free as he might have hoped. He encountered power struggles both at a local level in the school where he taught and nationally. He established a newspaper, the Star of Liberia, but made an enemy of the Liberian President, Stephen Benson, when he published an anonymous letter criticising Benson’s administration. Matters deteriorated further when Benson took court proceedings over the administration of TMCs school. Eventually when Benson was re-elected in 1861 TMC postponed any further attempts to settle in Liberia and returned to the United States where most of the southern, slave-owning states had seceded from the Union and the Civil War had recently begun.

The War provided the black communities in the Northern States a with the opportunities not only to help free the slaves in the south but also to secure their own recognition as US citizens. For, in the words of Frederick Douglas, ‘Once let the black man get upon his person the brass letters US…there is no power on earth which can deny that he has earned the right to citizenship.’ But in in practice the latter was one of the reasons why it was not until January 1863 with the War going against the Union that Lincoln allowed black soldiers to be recruited. TMC was eager to help and by that summer he was not only leading the drive to recruit African Americans in Massachusetts but was also in charge of a company established to help repel a threatened rebel attack on Harrisburg. However, he quickly became disenchanted by the racial segregation and discrimination applied in the Army. The African Americans were formed into so-called ‘colored’ regiments. For many months, they were paid only as labourers and not as soldiers and it was not until the last months of the War that African Americans were granted commissions. Rather than accepting such discrimination he left the US in the autumn of 1863 for a speaking tour of England designed to counteract the significant British support for the Confederacy.

For the next ten months or so Chester gave a series of lectures on the American situation and its effect on African Americans. He won praise for his oratory and an official of the US embassy wrote that he had ‘few superiors, white or black in the command of language and its appropriate use.’ But, as in Liberia, factional politics impeded his efforts. Obtaining the support of several English Emancipation Societies was made difficult by his longstanding association with the American Colonization Society and eventually TMC returned to the United States in the summer of 1864 having accepted the offer of a job as a war correspondent for the Philadelphia Press. The trip was of some personal value, however. He made contacts which might be useful if he returned to England to study.

By the time TMC arrived in the US the war had swung more in favour of the Federacy. Sherman had marched through Georgia and was to take Atlanta before eventually joining up with Grant in a siege of the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia. His many newspaper reports, of the siege during the next ten months demonstrate his skill as a communicator. Their exciting detail grips the readers’ attention, and their apparent objectivity lends them credence. At the same time, occasional subjective comments about the rebels conveyed the message that the Union army and especially the African American regiments will be victorious:

My attention was attracted by a huge volume of smoke, through the center of which like flames from the center of a volcano, a terrible blaze suddenly ascended, intermingled with dark objects which were thrown in every conceivable direction. Then followed a tremendous report and a spherical body of smoke which seemingly curled up to the clouds- all presenting a spectacle of more than ordinary grandeur. The dust now rose in a darkening confusion, ands literally obscured everything within half a mile of the scene. …

Shells and shot are continually being thrown inside our breast works occasionally wounding someone…Whenever such proceeding becomes annoying, our guns along the line…are opened which has the effect of silencing, for a time, the heavy firing of the enemy. The unceremonious argument of artillery is the only influence he heeds or the only reason he respects.

TMC’s role was not without personal danger. In January 1865 when reporting from the outskirts of Richmond, he narrowly escaped being killed when a Confederate shell landed only feet away from him but fortunately failed to explode.

On Tuesday 4 April 1865, the Union Army entered Richmond. Chester and other reporters established a press room in its Hall of Congress. He was sitting in the Speaker’s chair when a paroled Confederate officer entered the Hall and ordered him out. When he refused, the officer tried to remove him by force only to be met by TMC knocking him to the ground before continuing to write his dispatch and commenting ‘I thought I would exercise my rights as a belligerent’.

The end of the War did not mean the end of either segregation or racism. When hostilities ceased TMC returned to Pennsylvania where he helped to form the Pennsylvanian State Equal Rights League whose aims included protecting the African American community from racist attacks and promoting its interests for example by founding schools. One event organised by the League, notable because it demonstrated that the end of the War and abolition of slavery were only the start of a long journey towards racial equality, came as part of the victory celebrations. In May 1865, a Grand Parade was held in Washington with a march past of 150,000 Union soldiers However although nearly 180,000 so-called ‘colored’ soldiers had fought in the Union Army- and nearly 40,000 died- the only persons of colour allowed to take part were former slaves who appeared as labourers Not so in Pennsylvania where TMC both chaired the League’s committee which organised a three-day event to celebrate the State’s 10,000 veterans and acted as its parade’s Chief Marshall. Even here, racism was present. The editor of the Harrisburg Patriot labelled the celebration as ‘the Darkies Jubilee’ and reported that the League ‘wanted the niggers to vote, to hold office, to intermarry with whites, in fact, to rule America’.

Unsurprisingly instead of remaining in the United States, Chester again left for England to raise funds for the League but he found that anti-black sentiment had increased. Lectures were cancelled and contributions were poor. He therefore extended his efforts to the continent and to Russia where Alexander II had recently abolished serfdom and was struggling with the political and economic consequences in many ways similar to those facing the United States. TMC met with greater success than in England and was introduced to the Imperial Guard in St Petersburg and dined with the imperial family.

Chester had wanted to become a lawyer since his youth and now, possibly because he had the money to fund his studies (although its source is uncertain) and because it would assist his future whether in Liberia or the US he decided to read for the Bar and in June 1967 applied to be admitted to the Middle Temple. Although he had informally studied law under the guidance of a lawyer in Liberia in 1859/60 his only formal qualifications were his classical studies at Thetford Academy eleven years previously. The Inn ‘s regulations required something more but TMC felt himself unprepared to pass an exam in the time available. Therefore, he petitioned Parliament, (the Inn’s governing body of Benchers) to be admitted notwithstanding his inability to meet the usual entry requirements. Giving an account of his circumstances and plans he wrote:

[I] entreat this privilege, not so much for myself, as on behalf of the Negroes efforts, who are struggling under many adverse (?) circumstances to build up a commonwealth of learning, liberty and law upon the benighted coast of Africa.

By a bare majority, the Benchers granted the petition and on 3 June ‘Thomas Morris Chester. of Monrovia, Republic of Liberia, (33), third son of George Chester of Harrisburg, Dauphin, Pennsylvania. United States of America, merchant’ was admitted to the Inn as a student member.

Although a lack of finance had been a theme in TMCs educational plans which he estimated would cost more than $700 for the first year alone he took relatively spacious residential chambers in the Inn rather than more modest rooms elsewhere. They comprised three rooms and a kitchen and Chester claimed to have spent more than £1,000 fitting them out and installing gas. He also employed a live-in servant.

During Chester’s time at the Inn, he continued his work on behalf of Liberia and in 1868 he was appointed as aide de camp to its President, James Sprigges Payne. The Liberian economy was largely based on agriculture and urgently needed a boost. TMC’s post required him to travel extensively in the Law vacations to promote trading and political ties with European countries. In 1868, for example, on a four-month Baltic and Scandinavian tour he visited Brussels, Bremen, Hamburg, Stockholm, and Christiana (now Oslo). In early 1869, he was one of two commissioners employed to negotiate a trade treaty with Russia. He twice revisited Russia and having returned to London in late January was in Paris until April. Later that month, he was staying in Frankfurt.

When Chester returned to London at the start of the Trinity Term in 1869, he had two very unpleasant surprises. The previous November he had placed an advertisement, possibly relating to lectures he was giving or fund raising, in an unidentified newspaper in which he gave the address of his chambers. In doing so he may have unintentionally breached an unwritten rule preventing barristers (and he was not yet a barrister) advertising or a prohibition on using residential chambers for business purposes. Now in April 1869, someone-probably another student, Roger Yelverton, whose residential chambers shared the same staircase as TMC’s – told the Inn’s authorities about the advertisement. The Inn gave TMC notice to quit his chambers. TMC responded apologising to the Treasurer to have the notice withdrawn but stating that he would accept the decision if it were not:

If in my ignorance of your forms or your etiquette, being a stranger and a foreigner I have in this respect offended to the extent of being so summarily dealt with, I bow with that respectful fortitude to your decision which one feels who never intended to do any wrong.

It seems that the Notice was not withdrawn and in June TMC quit his chambers.

The second incident was even more unpleasant. Shortly after his return from Paris TMC received a ‘highly disrespectful’ letter from Yelverton accusing him of entertaining prostitutes in his chambers and alleging that women visiting him had ‘committed a nuisance’ on the staircase to the annoyance of other tenants. TMC made enquiries of the two other tenants whom he knew by sight, and they told him they knew nothing about the letter or the nuisances.

At first TMC was inclined to follow the advice from the Inn’s Under Treasurer to let the matter rest but afraid his reputation with the Inn might have suffered and concerned that it might affect his Call, he sent the Treasurer a full account of the matter emphasising his position with the Liberian government and his extensive dealings with the Russian Imperial Court and the Royal Courts of Denmark, Sweden and Saxony as well recounting that he had received ‘the courtesies and enjoying the hospitalities of some of the best representatives of European nobility’ . He admitted that he had been visited several times by ‘respectable ladies’ whom Yelverton had not only but even invited into his own chambers. But these were certainly not prostitutes.

Given the limited evidence available it is difficult to ascertain the truth of Yelverton’s allegations. Prostitution was rife in London, and it is likely that some prostitutes may have visited men in their chambers. The sanitary arrangements in the Temple, both generally and in chambers, were unsophisticated and in consequence nuisances were not uncommon. TMC told the Treasurer that women were to be seen ‘walking through the Temple at all hours looking for admirers or expecting friends,’ and these were known to avail themselves of staircases to relieve themselves. But he took pains to show that no nuisances on his staircase could have been caused by his lady visitors.

The Inn did not investigate the matter, but had it done so it is unlikely that the allegations would have been found proved. Incidents in his later life show that Yelverton lacked judgment but more tellingly, a few months after his letter to TMC his own conduct was investigated by the Inn’s Benchers. In June 1869, the same month in which he was Called, Yelverton had persuaded Dr Adam Thom, to allow him and his attorney father to represent him in a forthcoming prosecution of the directors of London’s leading discount house whom Thom alleged had defrauded him. Although it was agreed that Yelverton would act without a fee other than his personal expenses and his father would charge a fee lower than the normal one., three days after the trial started, Yelverton’s father, apparently with his son’s knowledge and consent, threatened to withdraw counsel from the case if fees were not paid. Following the Defendants’ acquittal Dr Thom complained to the Inn’s Benchers After an extensive inquiry the Benchers found Yelverton guilty of ‘grave impropriety and irregularity’ which had brought discredit on himself and his profession, adding that they were ‘obliged to express their great dissatisfaction’ with the evidence he had given. Yelverton was suspended from using the Hall, the Inn’s Library and Gardens until the following October.

The uncomfortable question though must be asked whether Yelverton had been motivated by racism. In his letter to the Treasurer, Chester clearly thought he was:

I envy neither the head nor the heart of that man who imagines that he has a private quarrel and seeks to invoke without cause or [?] an authority to which no high-toned gentleman would appeal in the interests of vindictiveness. Identified with a race whose whole history has been one of suffering and injustices I feel that however sensibly this ordeal may affect me….

In the 1860’s racial stereotyping and racism were widespread in England. Although there is no direct evidence that Yelverton shared these prejudices it is very difficult to accept that he would have acted as he did have TMC been, like him, a white student from Oxford.

Despite his fears, Chester’s standing with the Inn does not appear to have been affected by the complaints and on the Saturday 30 April 1870, having kept the required number of Terms and completing two courses of lectures and private classes he was Called to the English Bar.

It is doubtful that Chester ever intended to practice at the English Bar. Regardless of whether this could have been achieved this it seems that the atmosphere of English professional life did not appeal to him. A few months after his Call in his speech to school children in Pennsylvania he impliedly compared Britain unfavourably with the United States ‘which has so many resources to develop- which respects a man only for his individual worth and not for the greatness of his ancestors- which is everywhere recognising merit irrespective of complexion and which by its fundamental law has proclaimed the equality of all men.’ When he was admitted as student, he was probably undecided whether to live in Liberia or return permanently to the United States. In 1869, it seemed that his choice would be Liberia because, according to its Consul General in London, President Payne wanted TMC to carry out what he vaguely described as ‘the introduction of an important institution destined to be a powerful element in African civilisation’ and in September that year Chester was appointed Chairman of the Probate Court for the County of Monrovia. However, the appointment was conditional on his returning to Liberia by the following January and this would have prevented him taking his Bar exams. TMC unsuccessfully petitioned the Benchers to be excused the exams and so the offer lapsed. In any event success in Liberia would have been one of difficulty after his patron, President Payne, failed to be re-elected in January 1870.

Chester therefore returned to the United States but not before distinguishing himself in December 1870 at a trial at the Old Bailey where he was briefed to co-defend Edward Searey on the capital charge of murdering James Kennock. Both men lived and worked with two other cobblers at the home of David McGill. One evening they visited several pubs and began to quarrel during which Kennock struck Searey who fell to the ground striking his head. Searey was taken to the Middlesex Hospital where he was examined before being discharged. On the journey home, he told another employee that he would ‘do’ for Kennock before the next night. Later that night Searey struck the sleeping Kennock with a metal file before being bundled from the room. When he returned a few minutes later he and Kennock started fighting during which Searey stabbed Kennock with a cobbler’s knife, causing his death.

The case presented a formidable challenge for Chester and his junior, a Scots barrister called Hunter. Not only were the defence team out-gunned – the prosecution was led by an experienced Old Bailey advocate of at least nine years standing – but the facts, not least that Kennock had been stabbed seven times-, presented a damning case against their client. However, despite his recent Call, TMC was an experienced, confident, and mature orator and took great care in preparing for the trial. Although there is no transcript of the case, a detailed digest of the evidence enables the defence case plan to be reconstructed. It appears that he and Hunter decided there were two possible ways of raising a reasonable doubt in respect of the charge of murder: Searey’s actions were a result of the head injury he had suffered earlier and, self-defence. If the second were to succeed they would have to raise a doubt as to whether Searey had gone to the workshop to arm himself with a knife. His case before the committing magistrate had been that having used the knife earlier to pare his nails, he had left it in the fireplace in the bedroom.

The two-day trial began on the 12 December, less than five weeks after Kennock’s death. Among those in the public gallery was Moncure Conway, a white, former Unitarian minister from Virginia whom TMC may have met through Conway’s involvement with the cause of abolition. His short account of the trial written for an American newspaper provides a, possibly unique, portrait of TMC:

Mr Chester who formerly lived in Philadelphia and is very black, created a sensation when he took his place, arrayed in his white wig and black gown, among the eminent barristers who treated him with the utmost consideration.

The digest shows that TMC had carefully planned his cross-examination and worked on introducing an element of doubt in the jury’s mind. So, although none of the witnesses had seen the knife in the prisoner’s possession until after Kennock had been stabbed and McGill said that he personally never used a cobbler’s knife for paring his nails, under TMC’s cross-examination he conceded that ‘it might have been used for that: it might have been taken into the bedroom for that purpose. I can’t say for certain that it was in the workshop on Sunday night’. (Emphasis has been added)

Chester also demonstrated he had the skill of persuading witnesses to moderate their adverse evidence albeit only slightly. Thus, when the doctor who had examined Searey that evening said that the defendant had been intoxicated, under further questioning from TMC he conceded the impact might possibly have produced compression which might happen after some length of time, the effect of which would be to deprive a person of control over their actions.

The trial digest records only the evidence, and the closing submissions remain unknown. However, TMC and Hunter were able to persuade the jury to acquit Searey of murder, instead convicting him of manslaughter for which he was sentenced a to ten years’ penal servitude. Conway rightly credited this victory to TMC’s skill:

[This] negro lawyer, by sharp cross-examination, managed to shake the evidence regarding malice and deliberation as to save his client from the gallows.

Chester returned to the United States in early 1871 apparently with the intention of making his home there. However instead of settling in Pennsylvania he moved to Louisiana which had the largest free and wealthiest black community of the Deep South which, ante-bellum, had enjoyed far more rights, such as the ability to travel freely, than free blacks in northern states. And it was here rather than Pennsylvania that TMC decided to make his future. However, the political and social situation in Louisiana proved as difficult as anywhere else in the South. Prejudice and violence against African Americans continued and in 1872 more than three hundred white men, encouraged by white Democrat leaders, attacked a Court House in Louisiana and murdered at least one hundred men and women of colour in what became notorious as the Colfax massacre. By now Chester’s ability as a powerful orator had been recognised and he was chosen to open a large public protest meeting in New Orleans:

[Our brethren have] been savagely slaughtered, after they had surrendered under promise of protection and safety, by men who are daily plighting their fidelity to our interests and soliciting us to entrust them with the administration of public affairs….[When] we reflect how our blood has crimsoned every parish in the State, and with the full facts of this Grant massacre before us, we solemnly ask how long., oh Lord, holy and true, dust thou not judge and avenge our blood on them that dwell on the earth?

In addition to threats from white supremacists Chester encountered factional difficulties within the black political community similar to those he had found in Liberia, and which ultimately frustrated his personal plans in much the same way. The state Republican party which controlled the state government was bitterly divided over whether to pursue a programme of consolidation or a more ambitious one. TMC joined its more radical wing, and this nearly cost him his life. The Governor favoured consolidation and after a bitterly disputed election for the Lieutenant Governorship his mixed heritage candidate won but the radicals believed that there had been fraud. When the two factions clashed on New Year’s Day 1872, TMC was shot by a supporter of the successful candidate. Fortunately, he survived but although a Grand Jury found ‘true bills’ against the victorious candidate and three of his supporters, no trial seems to have taken place.

Chester was more fortunate in 1873 when he supported the campaign of William Kellog who was elected Governor. He was rewarded by being appointed both as a brigadier general in the state militia whose function was to support the civilian police authorities after Federal troops had been withdrawn and as the first African American Superintendent of Public Education for two state Divisions. His task as Superintendent was a difficult one. Budgets had been cut by a third and teachers were poorly paid and in consequence he was forced to recommend the closure of some schools. Nevertheless, he was praised by Jacque Gla, the state’s first African American senator, for his efforts:

[Chester manages his office] with more propriety and regularity than any of his predecessors and his appointment is looked on with pride by the colored people all over his district.

But as in Liberia Chester’s appointments depended on the patronage of those in power, When the Democrats gained control of the state in 1877, he lost all three.

In 1873 Chester had been admitted to the Louisiana Bar and quickly made a reputation for himself defending three poor men of colour charged with murder. Unlike the Old Bailey case three years earlier, his address to the jury was recorded:

That they are poor is their misfortune; that they have been accused with this crime is not their fault, and the responsibility of being black is assumed by Him who created them after His own image; and it would not be a violation of your oaths, if you permitted either of these circumstances to influence your judgement against the accused, but it would be an everlasting disgrace upon the administration of public justice in Louisiana.

In another case, TMC successfully appealed the conviction of a man accused of murdering a planter, the defendant being acquitted on the retrial.

As with his political activities Chester was concerned not only with establishing himself but also with promoting the interests of his community. The earlier cases under the Louisiana ‘equal rights and privileges’ legislation which prohibited discrimination on public transport and places of a public character such as transport, theatres and restaurants were brought by litigants who enjoyed a relative high status and had the support of white acquaintances. Now poorer people were represented by TMC one of the few lawyers to do so. The damages awarded were generally low but not in the case of a schoolteacher Emily Lobre, who when she asked to be served in a confectionary was told that she would have to sit upstairs. When she complied, she was told that she had to order downstairs only to find service was again refused. Chester was successful in securing her damages of $200.

In taking these cases TMC had the aim not just of securing compensation for his clients but also making the case against discrimination generally. As he argued in another case:

It is fatal to liberty when the color of a man’s skin, deepened by the sun of heaven in its fructifying influence in the land of their fathers, ostracizes him by violation of organic law, from the public cases and outlaws him in public estimation.

Sadly, when Democrats took political control of the state in 1877 the legislation became ineffective, and the path lay open for the segregation codes of the Jim Crow period which lasted until at least the Civil Rights Act of 1965.

In 1879, Chester, now in his mid-forties. married a twenty-three-year-old Florence Johnson, who was a schoolteacher like one of TMC’s sisters. They had a son, Morris who was to become a professor. Thereafter TMC spent much of his time in Harrisburg, playing no further part in state government although he managed to secure two short-lived Federal appointments. However, he continued in practice, dividing his time between Louisiana and Pennsylvania, being admitted to the Pennsylvanian Bar in 1881.

In 1888 Chester and Florence returned to live in New Orleans. His mother, Jane, who had developed a thriving catering business after the death of TMC’s father lived in Harrisburg and it was at her home that at the age of fifty-eight TMC died on the Friday 30 September 1892 apparently after a heart attack. He was buried in a segregated cemetery of Harrisburg. When Jane died in 1894, a newspaper recorded that she was the mother of TMC who was ‘one of the most accomplished colored men of his period.’ Florence lived until 1944 having spent almost fifty years as a teacher and school principal. Morris died in 1949, 124 years after his grandmother, whom he had known as a child, had been a slave.

It would be unfortunate if Chester were to be remembered only as the first African American to become be Called to the English Bar. Such labels, as Professor Olivette Otele has warned, can generate a misleading sense that the subjects of life stories such as his are exceptional characters whose lives were transformed by encounters with Europeans:

In such accounts the notion of exceptionalism is used as a plausible reason for their fame. Some of their stories are believed to have survived because of the extraordinary nature of their contribution to European societies. …Little however has been published about further aspects of their lives such as the close connection they may have had with other people of African descent. Some histories have been forgotten or their importance underestimated.

Chester’s membership of one of the Inns was discovered almost by accident rather than by directed archival research many years after his death when in the late 1980s Professor RJM Blackett was preparing his Civil War dispatches for publication. In this, he was not unique. Edward Haynes is another example. Born in Barbados of parents descended from slaves he was admitted to the Middle Temple in 1847 although he was never Called and left the Inn to study divinity at Trinity College Cambridge before being ordained a priest in the Church of England becoming the vicar of a Yorkshire parish. His legal background only became known in 2000 through research by the Africans in Yorkshire project and was not mentioned by Peter Fryer seminal Staying Power: The History of Black People in Britain written in 1984. Nor was Chester unique in being the first barrister of African descent. One of his student contemporaries at the Middle Temple, Samuel Lewis, was born in Freetown of parents rescued from a slave ship, and after his Call returned to Sierra Leone where he was appointed acting Chief Justice in 1886 and later knighted.

Chester’s life story shares other features common to nineteenth and early twentieth century law students or barristers of direct or indirect African heritage who have so far been identified. They were transients who came to London for education and to qualify before returning to their countries of origin to practise. For many, becoming a lawyer was only part of their identity and they were often active in politics and pan-African affairs. And it was often through these other activities that they have been identified as members of the Inns of Court. And so, the label of being ‘the first’ also distorts a rounded view of their lives. Although Chester may have self-identified as a lawyer, his life story shows that he was much more: an activist, educator, politician and journalist who twice served as a member of the military although as such never seeing active service. His story is one of adventure and complexity, lived at times of great change. Homer’s description of Odysseus, which TMC may have read as a classics student seems an appropriate epitaph:

This was a man of wide-ranging spirit who had wandered long and far. Many were those whose cities he viewed and whose minds he came to know; many the troubles that vexed his heart as he sailed the seas, labouring to save himself and his comrades

NOTE

Professor RJM Blackett’s biographical introduction to Chester’s War dispatches is an indispensable source for any life of TMC and I have drawn on it extensively especially as many of his sources are in the United States. However, he gives less than one page of the essay’s ninety-one to TMC’s time at the Middle Temple. Having the advantage of easier access to the Inn’s archives I have tried to remedy this as well as providing a background to incidents in TMC’s life which may be unfamiliar to readers.

Inevitably this essay is incomplete in part because of the difficulties of carrying out research in a time of COVID and more research is required into both primary and secondary sources.

Further Reading

RJM Blackett Thomas Morris Chester: Civil War Correspondent (1991)

Raymond Cocks The Middle Temple in the 19th Century in History of the Middle Temple (2011) ed Richard Havery Chapter 4

Eric Foner A Short History of Reconstruction (1990)

Peter Fryer Staying Power: The history of black people in Britain (1984) Chapters 8 and 9

John Mitchell Thomas Morris Chester: Activist, Advocate and Middle Templar (2020).

Olivette Otele African Europeans: An Untold History (2020) Introduction and Epilogue.

Master John Mitchell was Called in 1972 and made a Bencher in 2012. He was appointed a District Judge in 1999 and a Circuit Judge in November 2006, sitting in both the County Court and the Family Court in London. He retired in 2017. He was Chairman of the Middle Temple Historical Society and was Lent Reader in 2021. Master Mitchell passed away on Saturday 27 March 2021.