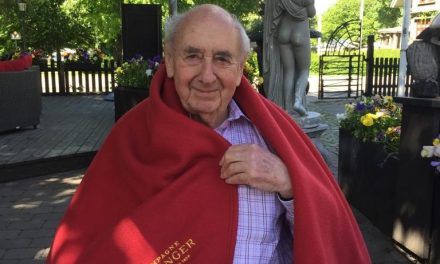

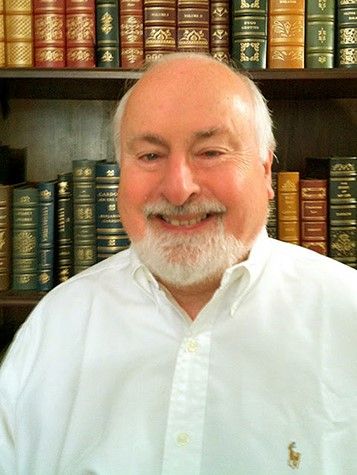

Peter Murphy, who died on Friday 29 July 2022 at the age of 76, was a writer and a lawyer who had a varied career spread over three countries.

He was born on 10 February 1946 into a largely Welsh family. Both his parents were born in Wales, although his father’s family were immigrants to South Wales from Cork. These circumstances, and the later circumstance of being a contemporary at Cambridge of the legendary Irish centre Mike Gibson, were to become the foundation of his loyalties in the world of international rugby, which were: Wales, Ireland, and whoever is playing England, in that order. But his club loyalty was with Harlequins, whose dedication to playing attractive rugby was something he much admired.

His father William ‘Bill’ Murphy was a chemical engineer, whose work for the government during the Second World War resulted in frequent moves. His mother, Rhiannon, née Rees, was a schoolteacher, but became and remained a homemaker once the War ended. After the War, Bill’s career took him to Lancashire, where Peter grew up, first in Widnes (now, sadly, in Cheshire) but more significantly in Blackburn, where he was educated at Queen Elizabeth’s Grammar School. At school he excelled in modern languages, and always retained a fondness for studying them. He was fluent in both written and spoken French, and later in life acquired some German, Spanish, Italian, Dutch and Portuguese. He was also a keen chess player, winning the British under-15 championship at Aberystwyth in 1961.

Peter went up to Downing College, Cambridge, in 1963 and graduated in 1966, but under the influence of his tutor, John Hopkins, stayed on to take his LL.B. in international law in 1967, a decision which was to prove valuable during his later career. He was Called to the Bar by Middle Temple in 1968 and undertook pupillage with Gilbert Rodway in the chambers of Joseph Jackson QC, the leading set for divorce and family law at the time. But Peter’s real interest was in criminal law, and he soon joined chambers being set up by Jeffrey Thomas, then not only a well-known defence barrister, but also a rising star in the Labour Party, as the MP for Abertillery and later shadow Solicitor-General. Peter was Thomas’ first junior when he took Silk not long after starting his chambers. The case was a long fraud trial at the Old Bailey, which Peter handled almost single-handedly while his leader was under a three-line whip in the House of Commons, for which he was rewarded with his red bag.

His practice began to take off. But these were hard times for barristers, with inflation running at a very high level and fees routinely paid late. In 1968 Peter had married Shirley Henderson, and they had a son, Christopher. But the marriage was dissolved in 1973, by which time Peter was living with Hilary Pearson, a barrister practising in the field of intellectual property. They married in 1973. Discouraged by economic conditions, Peter left the Bar and became a teacher at the Inns of Court School of Law, where he taught many future judges and legal luminaries. Among them was a Californian lawyer, Eric Bettelheim, son of the distinguished child psychologist Bruno Bettelheim. Eric suggested the idea that Peter and Hilary should try their luck in California, and after much soul-searching they interviewed for, and with Eric’s help, obtained legal positions in San Francisco. They emigrated in 1980.

While teaching at the Inns of Court School of Law, Peter had made his first foray into writing, and just before he emigrated, he published A Practical Approach to Evidence, later, as from the fifth edition, renamed Murphy on Evidence. The book’s novel style of combining academic treatment of the subject with a practical courtroom approach to the rules of evidence was instantly attractive to students. At the time of his death, the book continues to enjoy new editions, though Peter handed over his writing to Richard Glover when he was appointed a judge in 2007. Peter was always very proud that the guru of English evidence law, Professor Sir Rupert Cross, whom he had come to know through the Inns of Court School, gave the book his strong support and recommendation.

Peter and Hilary moved from San Francisco to Houston, Texas, in 1984. This was Hilary’s move, to a prestigious intellectual property firm. Peter followed, and with some reluctance accepted a professorship at South Texas College of Law, to teach evidence and trial advocacy. Although he started out with misgivings, intending to ‘give it a year and see’, it was a move that was to change his life in every way. He would remain a member of the faculty for more than 20 years. He relished the American trial process, and for ten years ran the South Texas trial advocacy competition teams, winning, as coach, two out of the three national championships for student advocates.

During the same period, his publishers, Blackstone Press, invited him to become the first editor-in-chief of Blackstone’s Criminal Practice, an extraordinarily daring move to compete in the practitioner’s market with the iconic Archbold, which had held pride of place since 1822. Peter oversaw the preparation of this huge work between 1986 and its first publication in 1991 and continued as editor-in-chief of successive annual editions. He relinquished the role on becoming a judge in 2007. Blackstone continues to flourish alongside Archbold and is now often described as the leading practitioner’s work on criminal law.

In 1983, Peter received a letter from Chief Justice Warren Burger, inviting him to serve on the ad hoc committee of the Judicial Conference, tasked with establishing the American Inns of Court Foundation. As Chief Justice, Burger was an Honorary Bencher of Middle Temple and invited Peter as a fellow member of his Inn. Peter had also come to the attention of Judge A. Sherman Christensen, who had overseen the creation of the first ever American Inn in Utah in 1980, and who was to chair the ad hoc committee. Peter served on the committee for its allotted two years, and when the Foundation was established in 1985, became a founding trustee, serving on the board continuously until 1999, when he was appointed an emeritus trustee. The American Inns of court are groups of judges, lawyers and law students dedicated to excellence in the practice of law. Burger said publicly that it was the legacy of which he was most proud, and Peter worked closely with him for a number of years. When the ad hoc committee started work there were six American Inns, not all of which were working well. By the time Peter left the board there were well over 300. He and fellow board members such as Professor Sherman Cohn, Ralph Dewsnup, Mike Coffield, Jim George and Tony Cotter work tirelessly to create new Inns and to encourage existing Inns.

The strain of the move to Houston was to spell the end of the marriage to Hilary. But in 1992, Peter met Christine ‘Chris’ Pulliam. They were both taking a class on astrology as an antidote to their demanding professional work – Chris designed pipeline installations for oil companies. They fell in love quickly and married. They celebrated their 25th anniversary in 2017 and Chris survives him. They had a happy and adventurous life together.

In 1998, Peter’s former student Cynthia Sinatra, married to Frank Sinatra, Jr, asked him to work with her on a case she had taken at the International Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) based in The Hague, the Netherlands. After this initial case, Peter practiced at the ICTY until 2007, and he and Chris lived in The Hague for much of that time. Peter remained on the South Texas faculty. His Dean was content as long he provided openings at the ICTY for student interns and cultivated a strong relationship with the law faculty at Leiden University, both of which he did. He taught on Leiden’s LL.M. programme in international criminal law. By this time, Chris had left the pipeline business and gladly learned to be a case manager for Peter’s defence teams at the ICTY. She brought her organisational skills to bear on the thousands of documents involved, managing the student interns at the same time, with such aplomb that the lawyers sent her to handle the regular status conferences required by the judges, working with her opposite number in the Office of the Prosecutor. They were probably the only two people who knew how many documents there were, and how many still needed translation.

In 2007, Peter was asked to return to England as a Circuit Judge and finally resigned from the South Texas faculty. He sat initially in London; at Wood Green, Woolwich, and Blackfriars Crown Courts, but eventually gravitated out to Peterborough, where he became Resident Judge and Honorary Recorder of the city. While at Blackfriars, he gave a leading judgment in the case of R v D (R) regarding the circumstances in which a female defendant is entitled to wear a face covering in the Crown Court as an expression of her religious faith. It was a subject of great public interest and one which had frightened away both politicians and more senior judges. At the time of Peter’s death, his judgment remained the only definitive statement of the law on this point in English law. At Middle Temple, he was elected a Bencher in 2013, and served as Reader for the Autumn term of 2018. In 2020 he was appointed Master of the Library.

After his appointment to the Bench, Peter also served for more than a decade as a visiting teacher for L’École nationale de la magistrature in Paris and Bordeaux, helping to teach French judges and prosecutors the basic principles of the Common Law, and improving their command of English.

Peter had long had an interest in writing fiction, and in 2011 his first novel, Removal, a political thriller about the American Presidency, was published by No Exit Press. It was swiftly followed by a sequel, Test of Resolve. After his retirement from the Bench in 2015, the pace of his writing increased greatly. He created the Ben Schroeder series of legal thrillers, featuring a barrister in practice in London in the 1960s-1980s. He also created the Walden of Bermondsey series, a collection of humorous short stories, based in part on his own experience as a judge.

He is survived by his wife Chris, his son Christopher, a grandson Tyler, two granddaughters, Josie and Bella, and by a younger brother, Paul.

Peter Murphy, writer and lawyer, died on Friday 29 July 2022.