With the Hall and Bench Apartments free of engagements earlier this year, it was a good opportunity to conserve some items from the Inn’s collections that could not easily be moved or repaired in-situ. The bust of Edmund Plowden in Hall seemed like the perfect candidate, the bust and plinth being extremely heavy and difficult to move and both in need of attention. Edmund Plowden is commemorated here because he masterminded and oversaw the construction of the Hall when he was Treasurer for several years in the 1560s. The bust however was created over 300 years later in 1868, by a notable sculptor of his time, Morton Andrew Edwards.

The bust and plinth were in good condition generally but needed cleaning as the layer of protective wax which had been applied historically had accumulated dirt and grime, causing the white marble of the bust and the stone of the socle (the thin block under the bust serving to support it) and plinth to appear grey. There were some small losses and scratches to the stone, possibly from lifting and moving the object in the past. The paint in the coat of arms on the socle was abraded from handling and cleaning with the stone showing through on the high points.

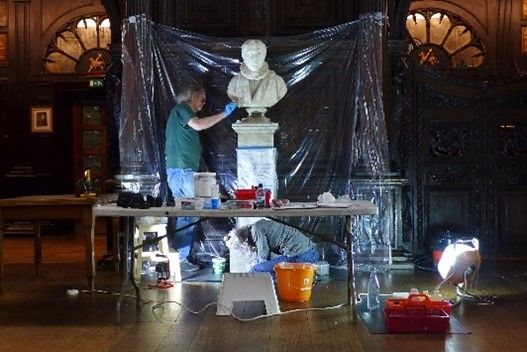

The expert conservators, Greg Howarth and Alexandra Kosinova, selected to carry out the task are accredited members of Icon (the Institute of Conservation). They can be seen here working in Hall and over a period of days removed all the wax with a mixture of white spirits and water emulsified with Triton X 100 and cotton swabs. The difference is visible in the picture below. The treated areas were rinsed with white spirits, and a new layer of wax was applied before being brushed off after 90 minutes, then the areas were polished with a cotton cloth.

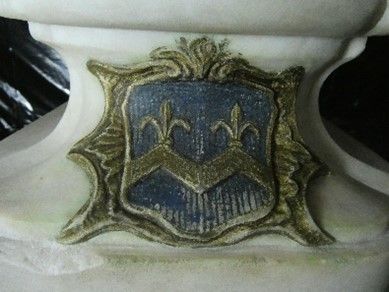

Before the wax was applied, the losses were filled with polyester resins that were pigmented to ensure the colour matched the stone. The coat of arms in the socle was treated differently – there was no wax removed, only discoloured varnish and abraded paint was retouched with artist’s acrylic paint and gold paint, then varnished with a resin. The pictures below show how subtle but effective retouching can be and how it can really improve things visually. What the eye can’t see of course is the preparatory work underneath, the layers applied before any retouching or infilling is done ensuring that all the work is completely reversible and never in direct contact with the original stone, marble or paint.

Though each problem area may have been treated differently with a variety of materials and techniques used, the result is uniform and even throughout the bust and plinth. There are no heavily worked areas in comparison to undertreated ones; evidence of the work of conservators who have spent years acquiring experience, knowledge and confidence to get it just right!

Uniformity was also the key priority for conservation work that was being carried out in the Parliament Chamber corridor around the same time. On the south wall there, many of the early to mid-20th Century panels are displayed and are generally in good condition, but several them visually present minor disparities that distract the eye, rather than allowing it to appreciate the panels as an inter-related group. Things like chipped paint, paint spatters, scratches and scuffed coating on the frames which showed the bright gold underneath were the main problems. We brought our specialist panel conservator, also an accredited member of Icon, in to work on the group in-situ to re-establish the visual homogeny originally exhibited, by treating each panel individually but mindful of the bigger picture, so to speak! Over several days, Mary Bustin worked on the panels either in the corridor or in the Parliament Chamber where a temporary studio was set up for the more complex work, equipped with microscope, easel, lights and all the necessary conservation tools and materials, as seen in the picture below.

The panels were surface cleaned, flaking paint was consolidated and small losses were filled in and retouched.

In addition to stabilising the panels and improving their appearance, our conservator also had to deal with the tricky issue of constantly shifting light levels in the corridor, which is lit both by natural light shining through the glass roof panels and the corridor lights which can be switched on or off several times during the day as circumstances necessitate. Retouched areas in the panels and frames, especially the gilded sections, may be invisible in certain light conditions but more apparent if, for example, the sun is shining and the lights are on, a phenomenon known as illuminant metamerism! Fortunately, this was avoided as our conservator only used modern substitutes with similar spectral reflectance curves to the original pigments.

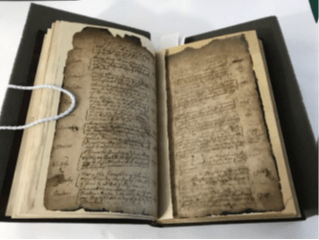

One object that was sent off-site for conservation was one of three Temple Church Registers that were deposited in the Inns Archival store by the Master of the Temple in 2000. These registers contain records of the marriages, baptisms and burials that took place in the church from the 1600s to the 1940s. They were stored at Temple Church but were severely damaged by fire and water during the Blitz on the night of Saturday 10 May 1941. Thankfully, they were saved and sent to the Public Record Office (PRO) in Chancery Lane for restoration. The pages were badly burnt at the edges with many pages having lost them completely, the ink had bled and the book covers were in such bad condition that they were beyond repair. At the PRO the registers were given cutting-edge treatment for the time, with archival paper and silk gauze used to repair and support the pages of manuscript. The registers were re-bound in leather and on completion were sent back to Temple Church for posterity. Fast-forwarding to 2019 though, it was apparent that the registers were again in trouble, even though they were now being kept in environmentally controlled conditions. It was difficult to open the volume fully, the pages were brown and brittle – the paper was breaking along the repair and lined edges and the text was corroded in places, as seen in these pictures:

It was not known at the time that the silk and animal glue would degrade and become brittle, causing the paper to become brittle and crumble too. The binding was too tight, and the repair paper was too heavy, causing cracking along the edges of the damaged paper. To complicate things further, iron gall ink used to write in the register was continuing to corrode the paper (high humidity causes the ink to react with the paper and destroy the cellulose that the paper is made from) as this corrosion hadn’t been mitigated originally. Using the register in this condition would have caused more damage, and it was sent off for several months for full conservation treatment in the Sussex Conservation Consortium book and paper conservation studio in the South Downs, run by Ruth Stevens and Ian Watson, both accredited members of Icon.

Because the register had numerous complex issues, the conservators created a timeline treatment document for us, dividing the project into smaller and more manageable segments and liaised with us during and at the end of each stage, sending photographs and written updates. An excellent video was made to record the different stages and it can be seen here

Each page was washed to remove impurities and acidity, to reduce the discolouration and soften the adhesive of the original repairs. The suction table was used to hold the wet paper in position whilst the old repairs were removed – the paper was so fragile that it could have easily come away with the repairs otherwise. The phytate treatment ensured the active part of the iron gall ink was washed away, slowing down the corrosion rate considerably. An alkaline buffer was added and gelatine size brushed on to complete the stabilisation treatment, leaving the pages flexible and strong again. The pages were then repaired and rebound into a flexible binding.

A lot of materials and techniques used in western paper conservation come from the Japanese conservation tradition, which itself was founded on traditional mounting techniques used to produce hand scrolls, sliding doors and folding screens, the oldest dating from the 8th Century. The repair paper, adhesive and brushes seen in the video are all Japanese as are the techniques used when brushing, repairing and infilling. Japanese repair paper, or washi, is structurally very strong, clean, and is made in a multitude of different weights, textures and colours. Japanese brushes are used for wetting paper, pasting, pressing papers and linings together and their bristles are often goat, deer, horsehair, or from palm trees. The secret is to be able to match the right paper with the right brush, using the correct technique!

Having been rebound in a more sympathetic binding the book is now back in the archives, fully accessible and much healthier, thanks to the expert work of the conservators… now only two more to go!

Written by

Siobhan Prendergast

Middle Temple Conservator