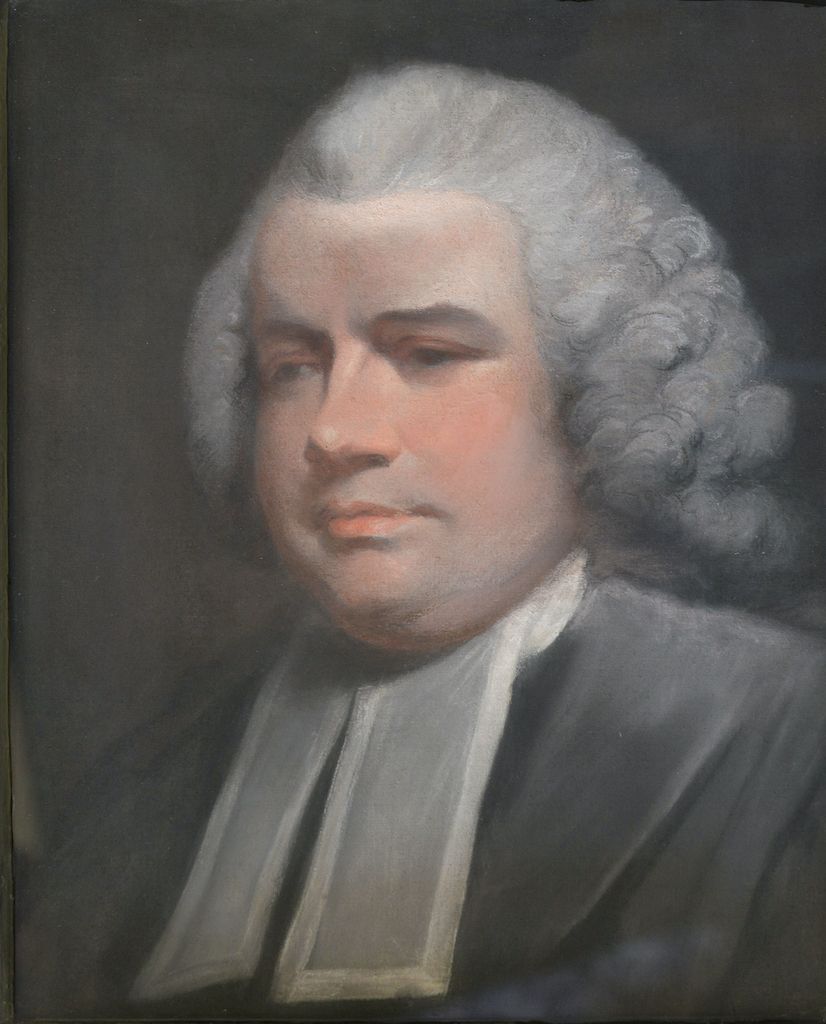

In our Parliament Chamber there hangs several portraits whose artists stood in the highest rank. One of them is that of Lloyd Kenyon, later 1st Baron Kenyon (1732-1802), the work of two of our finest portraitists of the late 18th and early 19th Centuries: George Romney (1734-1802) and Sir Martin Archer Shee P.R.A. (1769-1850).

Kenyon exemplified the able young person, an outsider to London, with no special educational, social or other advantages, whose life was transformed by joining an Inn of Court and the decision to pursue a career at the Bar. He was appointed Attorney General in three government administrations, before being appointed Master of the Rolls in 1784 and Lord Chief Justice in 1788, a post he held for the next 14 years until his death.

Born at Gredington in Flintshire on Friday 5 October 1832, Kenyon was educated at the local day school and Ruthin grammar school. His formal education ended at the age of 14, when he became articled to a solicitor in Nantwich, Cheshire. He became a student of the Inn on Saturday 7 November 1750 but lack of money, and his unsuccessful pursuit of a partnership in Nantwich, delayed his reading for the Bar until 1753. In London he lived frugally, in a single rented room in Bell Yard, and studied intensively. He was Called on Tuesday 10 February 1756 but, initially getting hardly any work, he continued his practice of attending Westminster Hall, and noting the cases he heard in the King’s Bench Courts – especially Lord Mansfield’s; his case notes were later published as Kenyon’s Reports.

From Lord Kenyon’s Summing-up in R v Rev. Gilbert Wakefield, tried and convicted for seditious libel in a pro-Revolutionary pamphlet:

I beg leave to say that I see no good in what has lately taken place in the affairs of another country. I see no good in the murder of an innocent monarch. I see no good in the massacre of tens of thousands of the subjects of that innocent monarch. I see no good in the abolition of Christianity. I see no good in the depredations made upon commercial property. I see no good in the overthrow and utter ruin of whole kingdoms, states and countries. I see no good in the destruction of the state of a noble, brave and virtuous people, that of Switzerland.

The general right to the liberty of the press is neither more nor less than this, that a man may publish any thing which twelve of his countrymen think is not blameable, but that he ought to be punished if he publishes that which is blameable. This in plain common sense is the substance of all that has been said on the subject.

If you think that it is possible to keep government together with such publications passing through the hands of the people, you will say so by your verdict, and pronounce that this is not a libel, but in my opinion that would be the way to shake all law, all morality, all order, and all religion in society.

His financial fortunes much improved in the mid-1760s, when he started to devil for two very able lawyers: John Dunning, later Lord Ashburton, whose portrait also adorns the Inn’s walls, and Edward Thurlow, later Thurlow LC (I.T., 1754). Kenyon’s legal knowledge and quick mind attracted the attention of solicitors.

His court practice was never large – his style being considered too blunt and over-technical to appeal to juries. He successfully defended Lord George Gordon against a treason charge, but it was his junior, Thomas Erskine, who won the plaudits. However, Kenyon developed an outstanding opinions-based practice, turning out correct opinions on all areas of the law with the greatest facility and speed: ‘much’, as his friend the reformer William Wilberforce described it, ‘as a man would crack walnuts after dinner’.

His practice steadily increased such that by the late 1770s his annual income approached £6,000. He declined offers of judgeships in the King’s Bench and the Common Pleas, but in 1780 success came on four fronts: he took Silk; he was appointed Chief Justice of Chester (a post outside London, which enabled him to continue in practice); he became MP for Hindon in Wiltshire; and he was elected a Bencher.

His earnings further increased: by 1782 his fees exceeded £11,000. Between 1782 and 1784, Kenyon was appointed Attorney-General in the successive (but politically diverse) administrations of the Earl of Shelburne (Whig), the Duke of Portland (Whig) and William Pitt (Tory). But it was in the law, not politics, where his future lay. In 1784, Pitt made him a baronet, and he was appointed Master of the Rolls, where he applied the law strictly, and impressed with his speedy decision-making and intolerance of professional delays. (He once struck out an entire List for the absence of Counsel and solicitors.)

In 1788, Kenyon was made Lord Chief Justice – an appointment delayed by Lord Mansfield’s opposition, clinging to office. There had also been some unease in the legal profession at Kenyon’s lack of any significant criminal practice at the Bar and at his blunt and boorish manners on the Bench. Even so, many agreed with James Boswell’s assessment of Kenyon as a hard-working ‘real lawyer’, who would be ‘a good fuller’s mill to thicken and consolidate the law’, this being ‘very necessary after the loose texture which Lord Mansfield had given it’.

In his 14 years as Lord Chief Justice, Kenyon belied expectations that he would prove to be any mere consolidator of the law. In an age of great political and social unrest, he interpreted and moulded the law expansively and in ways that reflected his views as to society’s needs for personal morality, commercial morality and the maintenance of public order. He came down especially hard on illegal gambling and adultery (then ‘criminal conversation’), for which he encouraged juries to award exemplary damages. He also railed against duelling – another fashionable pastime – stating as a ‘most clean’ proposition of law, ‘that if men will coolly go out on errands of this kind, and death ensues, beyond all controversy they are involved in the crime of murder’. Yet, Kenyon was generally reluctant to impose the death sentence and William Wilberforce commended him for advocating ‘a less sanguinary system’ of penal laws.

This was a turbulent age. Kenyon condemned the ‘horrid doctrines’ blown into the country from Revolutionary France and supported the Pitt Government’s wide interpretation of its new law of seditious libel, as his R v Wakefield summing-up illustrates. Pitt, Thurlow and King George the Third each consulted him extensively, the latter on constitutional issues such as the 1788 Regency question and Catholic emancipation in Ireland, and on private business matters concerning the King or the Queen.

Nor did he lack judicial boldness: in 1772, Parliament had swept away all statutory penalties for the marketing practices of ‘engrossing’ or ‘forestalling’ hops, practices which artificially raised market prices. But when in 1795-1796 and 1800-1801 wholesalers’ response to drastic food shortages and famines was to corner and hoard supplies and to raise prices, Kenyon’s response was that such conduct remained criminal offences at common law. He encouraged the successful prosecutions in R v Rusby (corn dealer) and R v Waddington (hops dealer), claiming after the guilty verdicts that the defendants were using market-rigging to profiteer, and had brought ‘a torrent of affliction to the poor’ by making the necessities of life unaffordable.

In Kenyon’s personal life, accounts describe his ‘sparing and abstemious’ living, his lack of refinement, his shabby dressing; his giving ‘no space whatever to dissipation’, and his parsimony bordering on avarice. They attest, too, to his generosity to his local poor, to his professional kindnesses to young Barristers and to his capacity for maintaining enduring friendships with lawyers and non-lawyers alike.

He enlarged his estate at Gredington and in 1797 became Lord Lieutenant of his county. In 1800, his distress at the death of his eldest son made him ill; but he continued to sit as Chief Justice until his own death, in 1802.

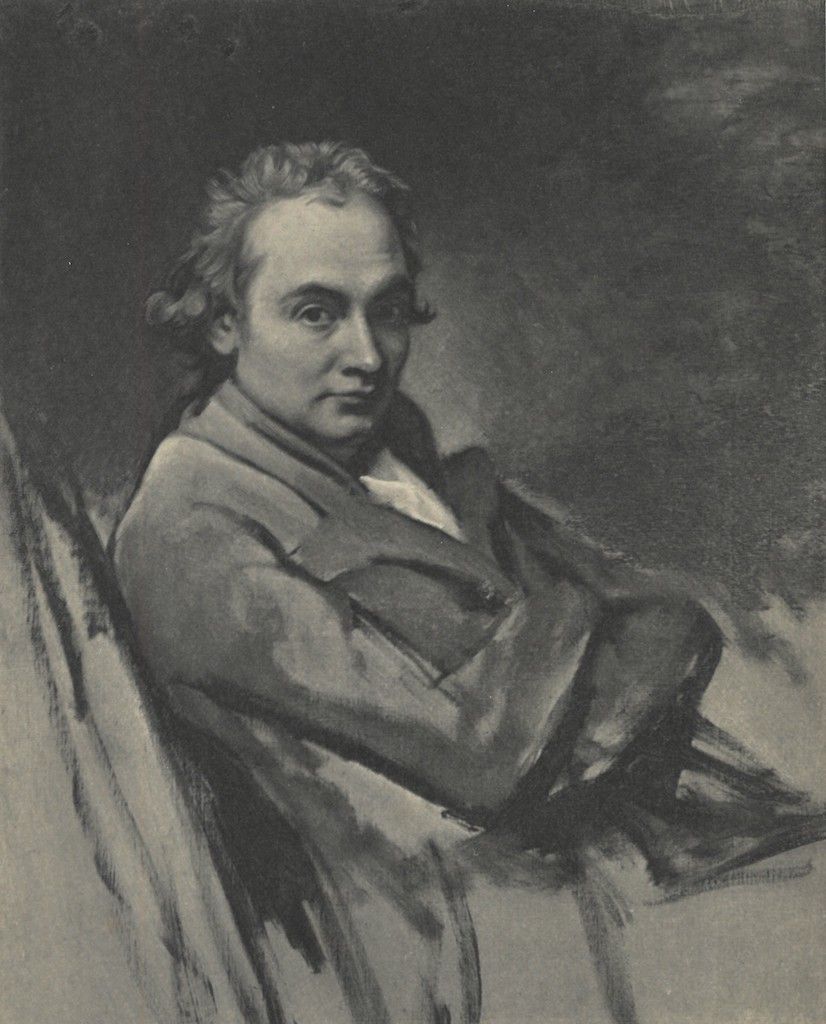

As for the portrait, Lord Thurlow LC may well have influenced the commissioning of George Romney. Thurlow had earlier pronounced ‘All the town is divided into two factions – the Reynolds and the Romney, and I am of the Romney’.

Romney had already painted several portraits of Thurlow – and one of his daughters – during the years before Kenyon attended Romney’s studio, on Wednesday 21 March 1792, for a session from 10:00 to 13:00.

That session would have sufficed for an artist of Romney’s speed and facility to render the head to near completion and to sketch the body and background, but not to produce a finished portrait. His ledger records that his price of 60 guineas was shared by him with Martin Archer Shee for his ‘finishing’ it.

The involvement of two of London’s finest portraitists was itself a compliment to Kenyon.

By that time, Reynolds having passed, Romney was without rival the leading portraitist, but over-burdened by commissions and prone to depression. Shee, however, was already receiving acclaim and, in 1798, would come to take over Romney’s studio in Cavendish Square. Still later Shee would become immortalised by Byron for his qualities both as artist and as poet: ‘And here let SHEE and Genius find a place, whose pen and pencil yield equal grace’. In 1830, he would succeed Sir Thomas Lawrence as President of the RA.

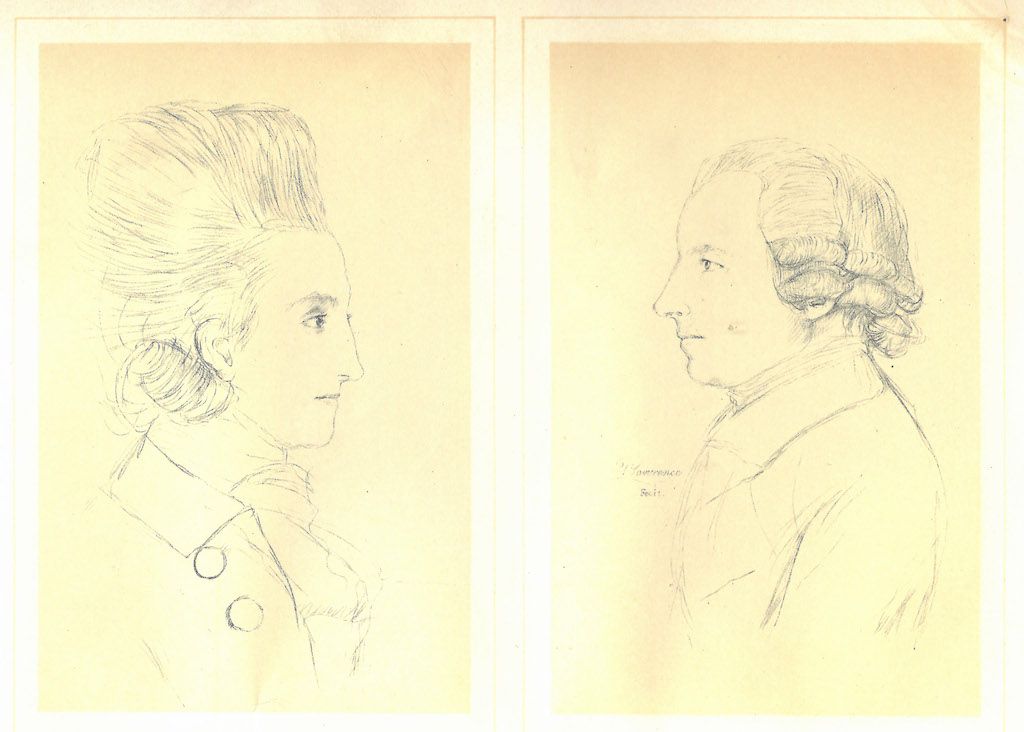

Not to be left out, Lawrence himself, at the age of 10, had sketched Kenyon and his wife, Mary, in two of his earliest surviving sketches– done at his father’s Inn, the Black Bear at Devizes, in 1779.

Thanks for acquiring this portrait of Kenyon are due to Master Richard Aikens, who in 1998 noted its availability for sale at Sotheby’s, and to Master Richard Hone for bidding for it.

We possess a further, smaller oil portrait of Kenyon presented by his second son, George Kenyon, 2nd Baron (1776-1855; Treasurer, 1822) in 1821, which is attributed to Shee.

Looking down at us today from these canvases, Kenyon would empathise with our efforts correctly to identify the artists who painted him. It was, after all, his judgment in Jendwine v Wade [1797] 2 Esp. 572 which held that the attribution in a catalogue of two pictures ‘the work of artists some centuries back’ to particular artists could not involve a warranty but a statement of opinion and one which left the determination of a painting’s authorship to the judgment of the buyer. That is a challenge to which the Inn has risen. Aided by a review of the Romney archive at the Fitzwilliam Museum Cambridge, it now appears clear that Romney painted and Shee finished the Inn’s larger portrait of Lloyd Kenyon, our foremost judge in the era of William Pitt, one of the greatest eras in our nation’s history.

Master Timothy Saloman was Called to the Bar in 1975 and educated in Classics and Law at Lincoln College, Oxford. A specialist practitioner in shipping law at 7KBW, he took Silk in 1993 and served many years as a Recorder of the Crown Court. He was made a Bencher in 2003 and, in 2020, Master of the House.