One of the more significant cases that Simon Brown heard as a High Court judge concerned ‘marital rape’. The defendant, a Yorkshireman, faced several charges at Sheffield crown court, including raping his wife. This presented legal difficulties because for 300 years common law had been understood to allow a husband the absolute right to sex with his wife.

Brown described being handed a large bundle of paperwork before being addressed by three leading barristers. ‘The court rose late and I undertook to give my ruling the following morning,’ he recalled. A dinner party at his lodgings that evening meant it was 11pm before he could start work. ‘I slept little. But by breakfast I had written my judgment, setting aside the assumptions of centuries past and seeking to justify this radical development in our law,’ he added. The higher courts agreed, albeit in a different case, and spousal rape eventually became a criminal offence in the Sexual Offences Act 2003.

Yet he was not so brave in 1995 when, sitting in the Divisional Court, he rejected a judicial review challenging the Ministry of Defence’s block on gay people serving in the military. Despite doing so ‘with hesitation and regret’, he suspected that the ban’s days were numbered and his judgment began: ‘Lawrence of Arabia would not be welcome in today’s armed forces.’ He received more than 100 letters on the subject, recalling: ‘They were about evenly divided between those who said, “How dare you traduce the memory of a great servant of the British Empire”. The other half said “Too true . . . we don’t want poofters like him around”.’

As a barrister he protected Paddington Bear from trademark infringements; in the High Court he heard Arthur Scargill’s civil battle with the police and Robert Maxwell’s 1985 libel action against Private Eye; as a Court of Appeal judge he overturned a jury’s verdict that The Sun newspaper’s allegations of match fixing against the goalkeeper Bruce Grobbelaar were libellous; and in the Supreme Court he was one of the justices who dismissed Julian Assange’s 2012 challenge to the order for his extradition to Sweden.

Brown’s first substantial appointment, as first junior Treasury counsel (known informally as Treasury Devil), came in 1979 and he recalled how each day ’at breakfast I would note the various stories in The Times upon which I would expect government lawyers to be consulting me later that day after court’. The workload was relentless and included on one occasion prosecuting Harriet Harman, then legal officer for the National Council for Civil Liberties, over allegations that she had handed confidential documents to the press.

After five years he was promoted to High Court Judge. In one case involving Arab terrorism, the prosecution suggested that any Jewish potential jurors might think it right to disqualify themselves. ‘Naturally, I agreed,’ he wrote. ‘But then I thought, goodness, what about me?’ He said nothing in court, but at lunchtime sought reassurance from Harry Woolf, later to be Master of the Rolls.

In 1992, Brown became a lord justice of appeal and from 1995 to 2000 was president of the Intelligence Services Tribunal, helping to investigate complaints against the intelligence services and GCHQ. However, he found that 99% of complaints were unfounded, writing that ‘paranoia is surprisingly widespread’.

Having been named a law lord in 2004, he chose as his territorial designation Eaton-under-Heywood to reflect the Shropshire parish close to his wife’s family seat. However, that was rejected by the Garter King of Arms who argued that it was not in his gazetteer. ’Starting to get desperate, I suggested he might care to telephone South Shropshire district council. This, somewhat grudgingly, he then did, happily with success,’ recalled Brown, whose voice was recalled as ’booming’ and ‘plummy’ by Shami Chakrabati in her book Of Women (2017).

He was well known both inside and beyond the legal profession for his entertaining anecdotes, telling with glee of the occasion that George Carman QC was due to appear before him at the usual starting time of 10:30am but needed to sober up after a night spent drinking and gambling. ‘My lord,’ Carman said, when he finally appeared. ‘I am so sorry; I had understood your lordship to have said yesterday that we would not be sitting until 11:15am today.’

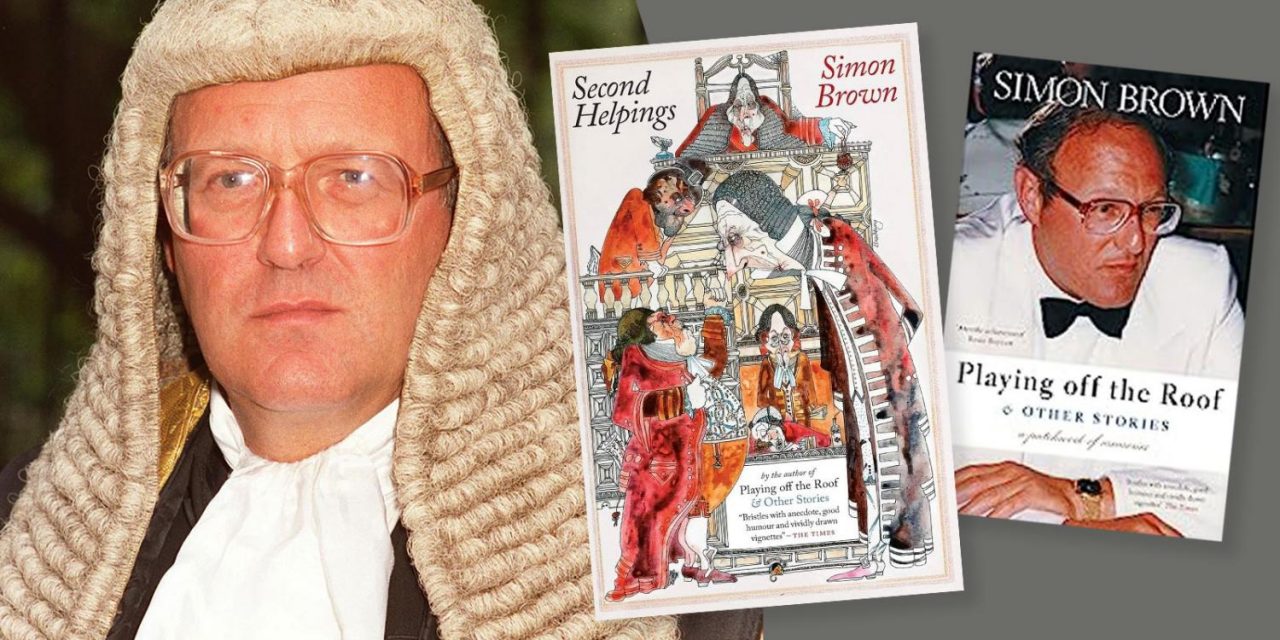

Brown’s first volume of memoirs, Playing off the Roof and Other Stories (2020), took its title from the occasion that his golfing partner, Nigel Wilkinson QC, played an errant shot that landed on the roof of the clubhouse. Brown went up a ladder and chipped the ball on to the green below, but the story reached the press with headlines such as: ‘Judge gets out of a hole by putting from the roof.’

Simon Denis Brown was born in Sheffield in 1937, the younger of two sons of Denis Brown, a jeweller, and his wife Elizabeth (née Abrahams); during the war his father served in Burma, so Brown had little memory of him until he was eight, when he returned.

The family left Sheffield when he was one and spent the war years at a large Victorian house in Nottinghamshire. They often took holidays at Scarborough, and he recalled one character-forming occasion on the south beach when he dropped his sandwich in the sand while showing off but was denied a replacement and instead required to eat the grit-laden bread.

At Stowe School he took a shine to history and won the school history prize. He was awarded a place to read history at Worcester College, Oxford, but first came National Service with the Royal Artillery. During one lengthy pub crawl, Brown drove his car off the road and into a ploughed field, where it came to rest on its side, mercifully with no injuries to his fellow officers. They were picked up by another car and returned to barracks where they drank two more bottles of champagne. ‘Many a driver 30 years later I was to sentence to lengthy prison terms for less,’ he recalled soberly.

He was posted to Malta, but en route his regiment was diverted to Cyprus for the Suez crisis, though they instead became involved in policing the Cypriot conflict. His duties involved censoring his men’s mail, but rather than finding military secrets being leaked he learnt ‘more about the anatomical possibilities of the sexual act than I had previously dreamt of’. Back in Britain he was an extra for Leslie Norman’s film Dunkirk (1958) starring John Mills and Richard Attenborough, lying on Camber Sands in East Sussex as explosives went off all around.

After a long summer holiday in New York stacking shelves in the basement of a 5th Avenue department store he went up to Oxford. He soon switched to law, in part because he had neglected a lengthy reading list but also to present his father with a ‘coherent alternative’ to taking over the family jewellery business. Before graduating he hitchhiked around postwar Europe, swam the Bosphorus from Asia to Europe and worked as a tour guide for wealthy American tourists.

Called to the Bar by Middle Temple in 1961, Brown did his pupillage in chambers in Crown Office Row, recalling that Owen Stable, his pupil master, was a ‘delightfully old-fashioned figure’ who still wore spats. His first brief was a driving case marked five guineas. ‘Here we are, sir. Our first five-guinea brief,’ said his clerk, handing over the file. ‘Now don’t you go asking any seven-guinea questions.’ After moving chambers a couple of times, he settled in Garden Court, sharing a room with William Macpherson, who later chaired the Stephen Lawrence inquiry. His workload was a mixed bag of cases. On one occasion he was defending a small supermarket chain on a charge of selling a mouldy steak-and-kidney pie when the trading standards officer inadvertently took the oath on the offending pie rather than the Bible. On the day President Kennedy was shot he was proofreading law reports in a small office at The Times next to the obituary section, ‘where that night, unsurprisingly, chaos reigned’.

At Oxford he had met Jennifer Buddicom, who later worked for the publisher Victor Gollancz. They were married in 1963 and had a daughter, Abigail, who was leader of the London Schools Symphony Orchestra and appeared as an actress in Grange Hill, and two sons, Daniel, a book designer, and Benedict, a playwright. 50 years ago, he and Jenny built a chalet in the Swiss Alps for skiing, though they also found it enjoyable in the summer.

A second volume of anecdotes, Second Helpings (2021) — updated as Second Helpings & Last Scrapings (2023) — was as amusing as the first. Among Brown’s many tales, his accounts of lawyers falling asleep in court are perhaps the most fun. He recalled how in later life Lord Denning nodded off for a few minutes on the dot of 3:00pm, though added: ‘He’d wake sharper than ever.’

However, his strongest memory of audible snores in court was personal: ‘Regrettably these emanated from my elderly father on the single occasion he came to witness his son’s forensic brilliance.’

Lord Brown of Eaton-under-Heywood, Supreme Court justice, 2009-12, was born on April 9, 1937. He died on July 7, 2023, aged 86.

Reproduced with kind permission from The Times