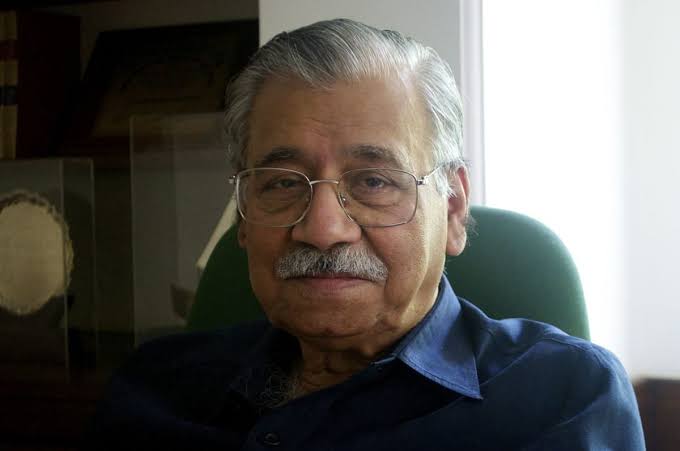

Chief Justice Aziz Mushabbar Ahmadi hailed from Gujarat and belonged to the Daudi Bohra Ismaili sect of Muslims. He had begun legal practice in Mumbai in1954, and a decade later had joined the lower judiciary in his state. In 1976, he was appointed a judge of the Gujarat High Court and was elevated to the Supreme Court in December 1988. After nearly six years he had assumed the mantle of Chief Justice — third Muslim Chief Justice of secular India after Mohammad Hidayatullah and Mirza Hameedullah Beg — and held the position until Monday 24 March 1997.

The celebrated case of SR Bommai v Union India decided by a nine-judge Bench in 1994 involved multiple issues including the secular character of the nation. Justice Ahmadi wrote a separate 37-page judgment ‘to indicate the areas of agreement and disagreement’ with the views expressed by his fellow judges on the Bench. Speaking of the ‘anxiety’ of Dr Ambedkar, chief architect of independent India’s Constitution, to ensure that the secular character of the nation ‘bequeathed by Mahatma Gandhi was not jeopardised’, he concluded that adequate provisions had been enshrined by him in the Constitution ‘to keep divisive forces in check so that interests of religious, linguistic and other groups were not prejudiced.’

The distinguished judge was on the Bench that decided the second Judges Appointment case in 1993 and gave birth to the collegium system for managing judicial appointments. He shared Justice SP Bharucha’s viewpoint in that case, and also endorsed his dissenting decision in Ismail Faruqui (1994) relating to the Ayodhya Land Acquisition Act and Presidential Reference about the alleged existence of a temple beneath the demolished mosque in the holy city. Writing the judgment in Padma Awards (1995), Ahmadi cautioned the powers that be to preserve the dignity and reverence of the awards by limiting their number and selectively choosing the awardees.

In Bhopal gas tragedy (1996) Ahmadi changed the charge of culpable homicide not amounting to murder against the accused to that of death by negligence, for which he faced the wrath of some human rights activists. The case was finally decided by the apex court, after his retirement, more or less in accordance with his ruling. In 2010 when the court rejected CBI’s curative petition seeking enhancement of punishments for the accused, Ahmadi’s point of view was vindicated.

In 1996, a few months after I took over the reins of the Minorities Commission, Ahmadi as CJI constituted a special 11-judge Bench of the court to have a fresh look at the interpretation of minorities’ educational rights under Article 30 of the Constitution of India. In an informal meeting at a social function, he told me how he wished the case to be decided before his retirement due early next year. I sought the Commission’s formal intervention in the case as amicus curiae, but due to government’s dilly-dallying in filing its response there was no progress until Ahmadi demitted office.

The Minorities Commission had been placed under an Act of Parliament in late 1992 and the first statutory Commission was constituted a year later. Justice Ahmadi was then in the last leg of his term as the CJI. In the fitness of things, the government of the day should have waited and offered him the Chair of the Commission, which in the past had been occupied by another former CJI, Hameedullah Beg, for seven years. The government in its wisdom, however, gave it to a former High Court judge.

In 1997 NHRC Chairman MN Venkatachaliah, Ahmadi’s predecessor as CJI, requested him to chair a committee constituted to suggest amendments in the Commission’s governing statute of 1993. He undertook the important assignment and submitted a significant report recommending some drastic measures, but no action was ever taken on it.

I demitted NCM chair towards the end of 1999. Sometime later former Prime Minister HD Deve Gowda — whose government had entrusted that onerous responsibility to me — asked me to suggest a ‘suitable Muslim VIP’ who could be the joint opposition candidate for the position of Vice-President of India, election for which was at hand. I confidentially obtained Justice Ahmadi’s consent and conveyed it to him. The former PM, perhaps on a careful assessment of the political situation of the day, eventually decided not to embarrass the highly dignified judge with the indignity of a possible defeat.

Later the same year the Aligarh Muslim University honoured itself by electing Justice Ahmadi as its Chancellor. In later years he initially accepted two important responsibilities but on a second thought gave up both. One of these was the presidency of a proposed body to be established by the name All India Muslim Education Board — and the other the chair of a government-appointed Working Group for negotiating peace in the troubled waters of Kashmir valley. In either case, he seemingly did not want to be the presiding deity of a noble mission which, he had soon realised, was destined to be an exercise in futility.

The Institute of Objective Studies, a centre for multidisciplinary research, conferred on Justice Ahmadi its Lifetime Achievement Award in 2007. The great judge, however, deserved a much greater honour. Juristic opinions about the value and veracity of some of his judicial decisions may vary, but those who knew him as a person from close quarters invariably found him a thorough gentleman — a dignified patriot through and through ever willing to serve the nation, but never to be dragged into unsavoury controversies and face indecencies.

Obituary reproduced with kind permission from the Muslim Mirror.