The monarchy has long been a link for many Pākehā New Zealanders to their roots. The royals are part of a package of the most wholesome elements of a semi-nostalgic Anglophilia, alongside such things as thatched cottages, David Attenborough, workplace sarcasm, and Paddington Bear. Queen Elizabeth II’s close relationship with the last, suggested to us by reliable internet sources and inferred to be that of Privy Counsellor–Privy Counselee, all the more endeared her as the safe executor of the modern constitutional monarch’s role of governance through tact, consultation, encouragement and warning (the latter by hard stare or otherwise).

It quickly becomes complicated, though.

For some of those who can trace ancestors back to Britain, it is to people who had good reason to depart; sometimes involuntarily and via the island off our North-West coast, Australia. For many Māori New Zealanders, the Crown signifies colonisation and generations of hurt, but, at the same time, the Crown is the counterparty to, and guarantor of, the 1840 Treaty of Waitangi, by which the New Zealand state was formed and that shared responsibility for governance between the British and Māori. Te Tiriti is New Zealand’s most significant constitutional document, and the key reason why New Zealand is the second of the three countries without a single codified, written constitution. While the numbers may not be on our side, and notwithstanding the recent, belated arrival of Hamilton on these shores, little convinces us we’ve backed the wrong horse.

Rule by monarch sits uneasily with many modern conceptions of what New Zealand is. We like to think that we value principles of meritocracy and egalitarianism that are inconsistent with hereditary political office: that most would say inherited power is unfair because it is unearned.

We also now increasingly believe we have a long island story to tell of our own, on our own: much of which predated the British arrival. We accept we are a small nation, but not that we are a small people. We were the conquerors of Everest, after all. And we potentially invented the Flat White.

Finally, the Governor-General model has its flaws. It is the viceroy model: the Governor-General is the head of state as the King’s representative. The King appoints them on the recommendation of the Prime Minister. The Governor-General’s functions then include appointing the Ministers of Crown, including the Prime Minister, informed by the Parliament returned by public elections.

But, as the power to appoint or recommend appointment implies the power to dismiss or recommend recall, in the most serious category of constitutional crisis, such as when it is unclear if a prime minister still has a mandate to govern, the Governor-General and Prime Minister can each attempt resolution by firing the other. This vagary led Australia to the famous 1975 Kerr–Whitlam crisis, where Governor-General Kerr dismissed Prime Minister Whitlam purportedly to avert political and fiscal calamity (without warning Whitlam of this intention, lest Whitlam remove him first). Even today, the affair is still is seen as a Big Deal (although largely only in Australia, à la Marnus Labuschagne). The Canadians have their own, more lyrical, King–Byng affair of 1926.

That the head of state’s reserve powers to remove a prime minister (among other things) is guided by convention and precedent from which one derives ‘don’t miss’ and little more, is a problem. The justiciability of the exercise of such powers is also unclear.

All these considerations favour a full independence.

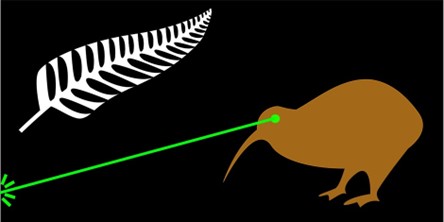

So, the view adhered to by many constitutional scholars in New Zealand was that at the end of the reign of Elizabeth II there would be some form of discussion about a possible New Zealand republic; perhaps, too, a codified constitution. Over the previous decade, some cautious steps were taken in anticipation. For one, the public generated a wealth of potential flags for that might replace the incumbent, most by the happy alchemy of Microsoft Paint and Cloudy Bay, in the course of a 2016 flag referendum. ‘Laser Kiwi flag’ (pictured) is the obvious frontrunner. For two, our foremost philosopher, Ms Yelich-O’Connor (also known as Lorde) , brought her campaign to be president directly to the public in her best known work, Royals, in 2013 (winning a Grammy on the way, incidentally. She most recently articulated the fundamentals of her environmental platform in Solar Power,in 2021).

Yet, in May 2023, New Zealanders’ focus on issues of succession attached far more to the Roy clan than to the Windsor. There has been little enthusiasm for any sort of republican discussion, notwithstanding the valiant efforts by some of our best constitutional scholars, who have been left to look on enviously at the surfeit of publication material that recent UK parliaments have served up to their colleagues overseas. That is the case even for a minimalist model: such as replacing the Governor-General with an analogous, but elected figure—and codifying their powers.

Perhaps it is still too early. You might also put this caution down to a commendable public instinct not to imperil what is now the King’s Birthday long weekend. Or, what a 2005 Select Committee examining constitutional arrangements characterised, forlornly, as New Zealanders’ instinct to ‘fix things when they need fixing, when they can fix them, without necessarily relating them to any grand philosophical scheme’. Given the national obsession with DIY renovation, it is no surprise our approach to constitutional change is the same approach we have to home repair.

And—perhaps unhelpfully—for all its flaws and ramshacklery, in practice, the constitutional model works well, and political crises are very few. And (I think) the monarchy contributes to that good functioning. For any participant in New Zealand government, the possibility of being the source of angst on the other side of the world, within the walls of an actual palace, where Netflix may have filmed The Crown, remains powerful persuasion to adhere to the conventions and reach the political compromises necessary to keep government running as it should. The view of the journalist Walter Bagehot—who in the 19th Century gave us the aforementioned tenets of royal governance by consultation, encouragement and warning—that the ‘dignified’ or pageant parts of the British government had soft but important constitutional power seems to resonate some 150 years later on the other side of the world. The fact that an explanatory attendance before the monarch in person requires 24 hours of flight time and risks layover at LAX must focus the mind as well.

Which is to say, for the meantime, and presuming Paddington keeps his Privy Council appointment, Charles III’s position as sovereign in right of Aotearoa seems secure.

William is a partner at the New Zealand law firm of Meredith Connell specialising in litigation, investigation, and regulatory work. He was Called to the English Bar in 2017.