Since 2006, when I was first employed by the Inn, I have been accumulating photographs of signatures, bookplates, notes and other signs of previous ownership in the Library’s rare book and manuscript collection. As such, when we were forced to close the Library to visitors in March 2020, I decided to make use of these photographs to set up regular blog posts that would highlight queries surrounding the unidentified marks of provenance found in some of these works. These posts can be viewed at:https://middletemplelibrary.wordpress.com/category/provenance-mysteries/.

I was inspired to create this blog feature by the Folger Shakespeare Library’s monthly blog posts, ‘What manner o’thing is your crocodile’, which present a ‘crocodile mystery’ and ask readers to identify the mystery image. I was hoping, albeit with a smaller audience than that of the Folger, to harness the power of the internet and crowd source answers to our provenance mysteries. Provenance research is a growing field and many early printed book researchers, librarians and archivists are recording and investigating provenance information.

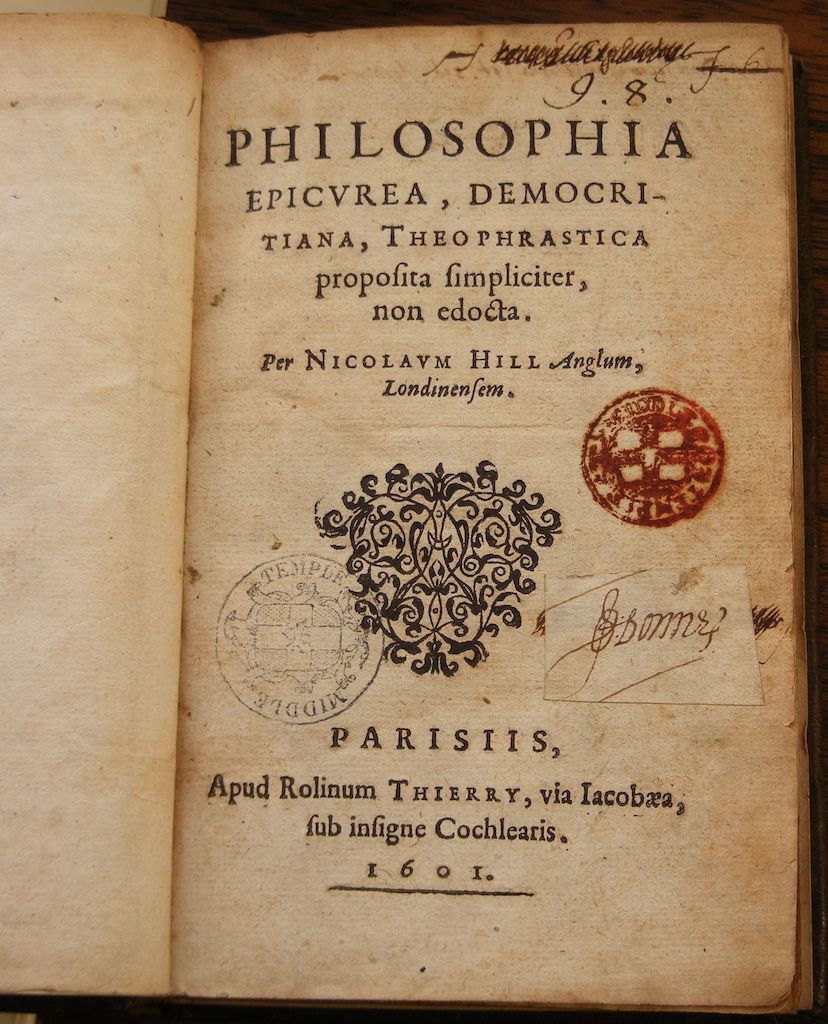

Provenance research involves using clues in books and manuscripts to trace the ownership of a volume. Often, provenance marks are very easy to spot and decipher, such as bookplates and book stamps, identifiable signatures and/or mottoes, and identifiable annotation styles. John Dee, for example, had a unique manner of annotating his books, and Middle Temple Library has four books that once belonged to him. John Donne’s signature and motto are very recognisable and the Library has 80 books that once belonged to him, all of which bear his signature and many his motto. The Library has at least six works that belonged to Ben Jonson and four retain his motto, ‘Tanquam explorator’ (five if we count one obscured version). One of the Jonson books, Nicolaus Hill’s Philosophia epicurea (Paris, 1601) also belonged to John Donne, who pasted a label with his signature on the title page, obscuring that of Jonson and scored through Jonson’s motto.

So far, 17 blog posts have been written, featuring items such as Flavius Josephus’ Opera, ad multorum codicum Latinorum, eorundem[que] uetustissimorum fidem recognita & castigate (Cologne, 1524); Nicolaus Copernicus’ De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (Basel, 1566); Thomas Hood’s The making and use of the geometricall instrument, called a sector (London, 1598); Tuba belli sacri Apocalypseos beati Iohannis adversus magnum illum antichristum, pontificem Romanum (s.l., 1622); among other works.

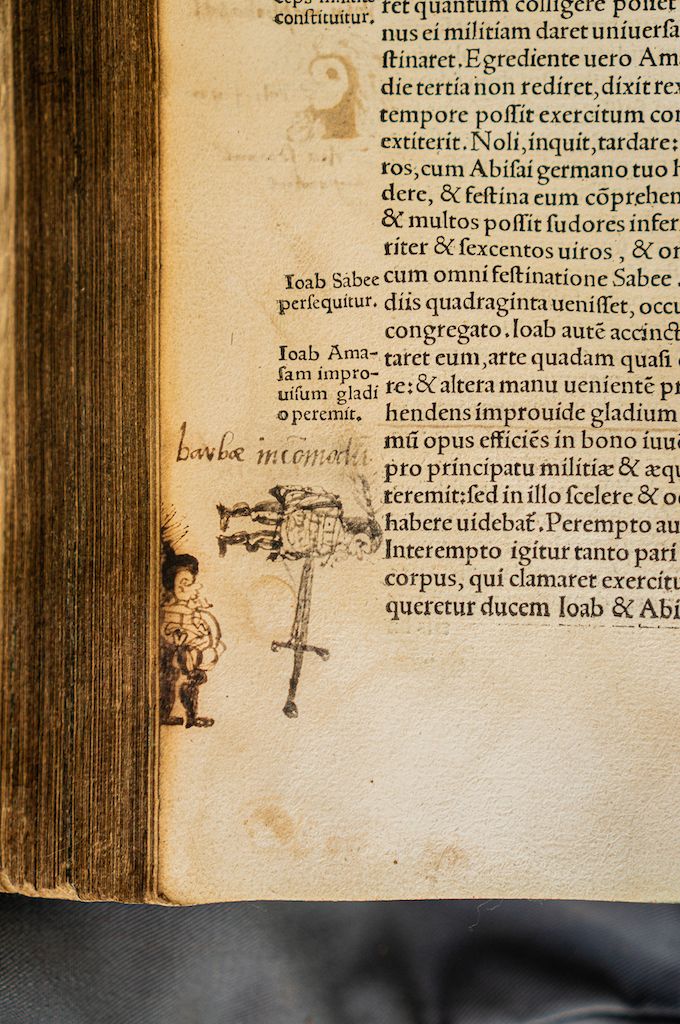

Flavius Josephus’ Opera shows a multitude of doodles and notes in the margins. One of the doodles features a man who was stabbed after being grabbed by the beard, that is to say, injury or death by beard. Another doodle depicts the funeral of Herod the Great. The Biblical story behind the first doodle was identified and explained by Jennifer Nelson, Reference Librarian at the Robbins Collection, University of California Berkeley School of Law, but the provenance remains a mystery, as it is very difficult to ascribe a doodle to any one book owner.

Despite Arthur Koestler’s 1959 suggestion that no one has ever actually read Copernicus’s De revolutionibus, Owen Gingerich’s work, The book nobody read, Middle Temple Library’s copy would beg to differ. A Renaissance reader has obviously read this copy, judging by the marginal annotations which have highlighted the principal points of the work (‘prima probatio’; ‘obiectio’; ‘solutio’, etc.). In fact, this book shows evidence of two different marginal hands, neither of which is Robert Ashley’s (1565-1641), the founder of the Library.

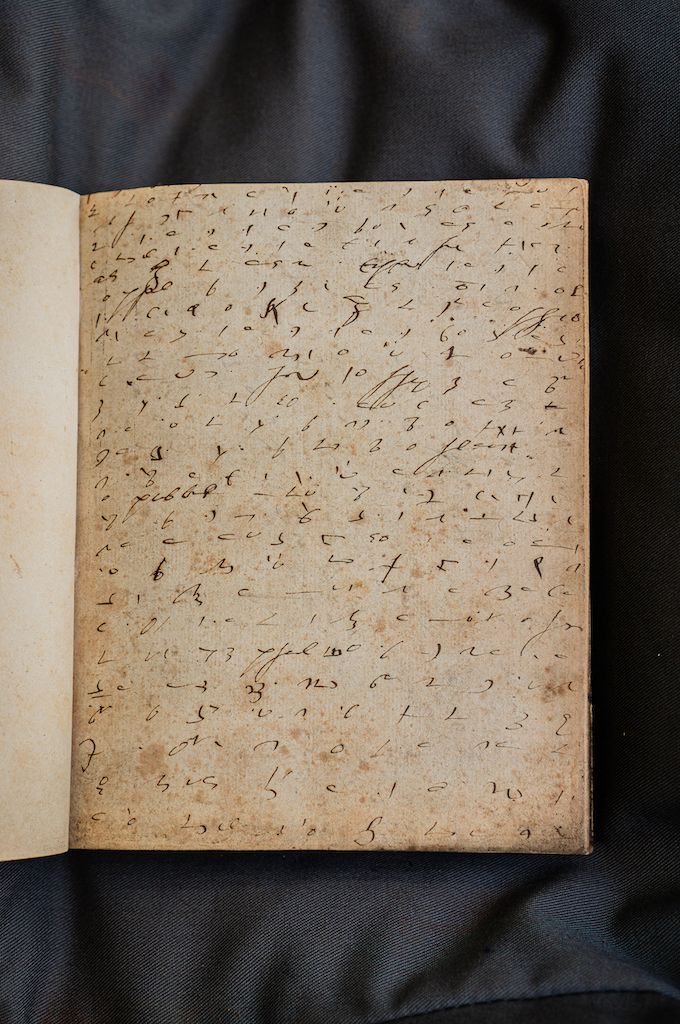

The Tuba belli sacri Apocalypseos beati Iohannis adversus magnum illum antichristum, pontificem Romanumis a commentary on Revelations and a controversial work on the Catholic Church and the Pope. As was customary at the time, it is bound with other titles: De praedestinatione compendium, by Giulio Serina (1580), Excercitatio scholastica de norma et normato, by Andreas Libavius (1628), and Dissertatio de autoritate ecclesiae by Johann Georg Dorsche (1628). Binding short works together into one sammelband volume was a common practice in the early modern period as it saved on binding costs. The work was published anonymously, but three different authors have variously been attributed: Eewout Teelinck, Willem Stephani or David Calderwood. The provenance mystery associated with the Middle Temple copy concerns the extensive notes on the book’s end-leaves, which are in shorthand. Timothy Underhill pointed out that this was shorthand and that it was common for such notes to be used as binder’s waste, that is, extraneous pieces of paper that the binder used as end-leaves, and which have nothing to do with the book itself. The person responsible for the notes remains unidentified.

Thomas Hood’s The making and use of the geometricall instrument, called a sector presented me with the most ambiguous provenance mystery. The sector was a calculating instrument in use from the 16th to the 21st Century and is often referred to as a proportional compass. Hood’s invention was contemporary to Galileo’s version and scholars disagree as to who first invented it. Thomas Hood was a lecturer in mathematics for the City of London. In his inaugural address of 1558, he declared: ‘the Lawyer thinketh him selfe cunning enough to handle his case, and therefore would laugh, if he should heere, that he standeth in need of our profession [i.e., mathematicians], yet have I knowne his sentence re-claimed by one of my coate’. The copy at Middle Temple contains four pages of extensive contemporary notes signed with the initials ‘D.G.’ at the end. The notes are headed: ‘In all eight lined tryangles the proportion of one syde to an other is such as the sine of of the angle, representing the one syde, hath to the sine of the angle each pertinge the other syde’. The notes then go on to discuss this theorem. But who was ‘D.G.’, and why have they gone to the trouble of writing out very comprehensive notes on this theorem, including illustrating the notes with quite beautiful diagrams? Was it a fellow mathematician? A contemporary of Hood? An instrument maker? Unfortunately, there is simply not enough information in the book to give us any further clues and our blog post has not resulted in anyone coming forward with an identification.

Some of the books featured in the blog posts need conservation and can be sponsored through a donation to the rare book sponsorship fund. These include the Tuba belli discussed above (estimated cost of repair is £450), as well as Laurent Joubert’s Medicinæ practicæ priores libri tres (Lyon, 1577). David Pearson, who was Director of Culture, Heritage and Libraries at the City of London Corporation and Director of the University of London Research Library Services prior to his retirement, wrote about this work for the blog. David has written and taught extensively on provenance research. We were unable to identify the owner of this book, who marked his or her initials, JD on the title page. This book is about medicine, plague and fever, and has an estimated cost of repair of £425. Dr Alex Samson of University College London wrote a blog post about our copy of Lucio Marineo’s De las cosas memorables de España (Alcala de Henares, 1539). This folio volume, about the history of Spain, unfortunately has extensive damage to it and would cost approximately £650 to repair, due to the paper repairs required. The copy at Middle Temple shows annotations in two distinct hands throughout.

If you would like to sponsor one of these books, or another book in the rare book and manuscript collection, please contact me via [email protected] to discuss further.

Renae Satterley completed her BA (Hons) in Social Anthropology at Concordia University and her MLIS at McGill University, both in Montreal, before moving to England in 2004. She joined the the Inn as Rare Books Librarian in 2006, before progressing to Senior Librarian in 2010 and Deputy Librarian in 2014, before being appointed Librarian in 2016.