‘The grand Saracenic arch of this structure is still in being. It has suffered little. The figures are very perfect, and it would be almost a proof of deficiency in sight, to say that they are impaired by time.’– Reuben d’Moundt, 1783 (abbreviated)

The Temple Church is one of the loveliest of London’s medieval monuments. Successive generations have reworked its internal decoration, but its structure and architectural details have remained unchanged since 1240. Even after the damage inflicted in the war, a mass of prints and photographs of the Church animated Walter Godfrey’s superlative restoration.

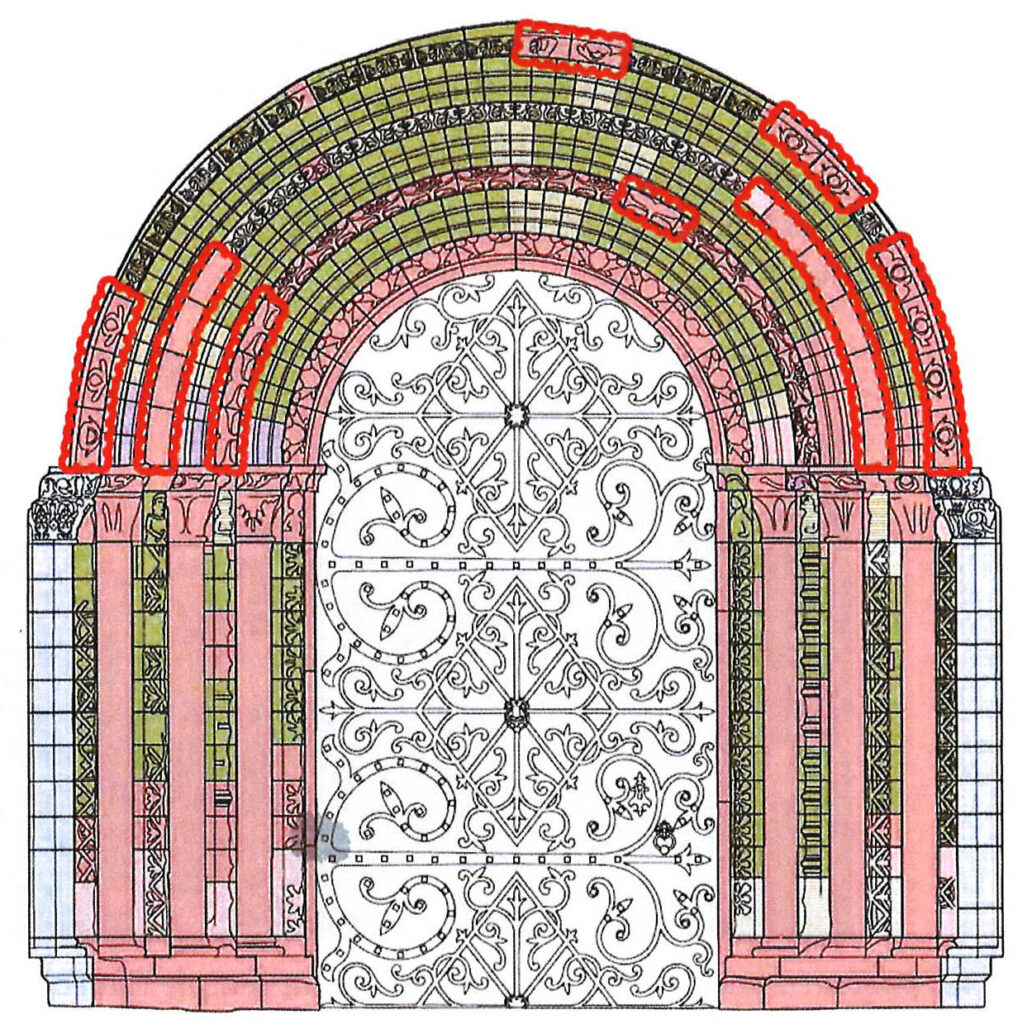

Just one element defied even Godfrey’s skill; and it is the most important single element of all. When you are next passing the Church’s West Porch to or from Fleet Street, take a moment to look over the railings at the carved West Doorway above and around the (magnificent!) arched door. Better still, find time to come through the iron gates and to take stock of this extraordinary artefact of the 12th Century. The seven-order archivolt, the capitals and demi-figures, and beneath them the clustered colonnettes. Here are various and rich carvings of vegetation, pinecones and semi-human heads, of latticework, rosettes, chevrons and beading. It must once have been a majestic doorway, giving onto a spectacular view through the Round and along the length of the Church.

It is now also a wreck. Gone to ruin are the lovely figures praised by d’Moundt. Photographs from the early 20th Century still show crisp, clear carving at every point of the doorway. London’s pollution and one chemical intervention after another – every one of them intended to stop the stone’s decay – have wrought havoc with the carvings. It has long been assumed that the most badly degraded stonework is from the 12th Century, the still-lovely carving from the 19th. But quite the opposite: in the last ten years, study of the doorway’s stone-cutting, joints and mortar (wholly different in the 12th and the 19th Centuries) has shown that all the beautiful, crisp stones are from the 12th Century, all the decayed stones from the 1840s. The illustrations to this article make the point far more clearly than could any description!

It is rightly impermissible to tamper with medieval stonework, however badly worn away; but there are no such constraints in revisiting a failed restoration of the 1840s. The doorway can be returned to a completeness and beauty unseen for over 100 years; and this time the result will last for centuries. We are still in touch with the Statutory Consultees over the details of the work that we can and will now undertake, and it will be some time before our planning application is finalised; but only a few years will pass before the doorway is again one of the glories of the Temple and of London.

It is thanks to the generous support of the two Inns that we can launch this programme of repair. (The Letters Patent granting the land of the Temple to the two Inns, 1608, specified among the Inns’ duties: ‘that they will well and sufficiently maintain and keep up the aforesaid Church, the chancel and the belfry of the same, and all other things in any way appurtenant to the said Church, in all respects and for all time to come, at their own expense, for the celebration there in perpetuity of divine service, the sacraments and sacramentals, and all other ecclesiastical offices, ministries and rites whatsoever in so far as it is befitting and has until now been used.)’ Once we turn to the whole envelope of structures to the west and north of the Church’s medieval interior, further needs and opportunities become clear.

The west doorway can at the moment rarely be used except in high summer – and for the bride’s entrance at weddings! – if the temperature inside is to be kept steady. But if we were to get planning permission for some careful temperature-control, the west door could become again the principal and spectacular entrance, for most of the year, that it was designed to be. For this we must make the doorway genuinely accessible to all visitors, with a ramp in the north-west churchyard; and the paving must be levelled. At this point the whole emphasis in access to the Church becomes the west porch and west doorway, appropriately lit to invite people to the glorious space within. We can re-imagine as the focal point, for anyone approaching the Church, its original, axial and re-beautified entrance.

Then comes the pressing need for far better facilities within our vestries, to prepare us for the most welcome arrival of girl-choristers from September 2024, for our many visitors and their retail-requirements, and for our rising concert – and audience -numbers. We need to ensure accessibility for everyone, safe provision for all the children, more space for our merchandise and for the preparation of refreshments, a smooth-flowing route for visitors in, through and out of the Church – and simply (far) more loos within the Church’s own compound. The back-stage facilities that have hardly been touched since Walter Godfrey finished his work here after the war can at last be re-equipped for the 21st Century, for our rising profile in London and beyond and for commercial uses to which we have never been able to plan before.

Again, the Inns are supporting the project with a very large grant. (The Disability Discrimination Act and safeguarding regulations clearly impose more appropriate but heavier responsibilities now than they did in decades gone by.) The Inns are rightly requiring that the result will enable us to add more to our annual income than the new provision will add to our annual costs. We have already benefited hugely from the support of the Julia and Hans Rausing Trust and of the Corporation of the City of London’s Community Infrastructure Levy Neighbourhood Fund. Furthermore, very generous help has been offered by two charities already well known to us here. And we are turning our minds to the substantial fundraising that undoubtedly lies ahead.

This is a major project. It is high on the list of governance and management tasks that we are undertaking as we transition into the Temple Church Trust. For the project we will continue to be grateful for the extraordinary expertise of Ian Garwood, Middle Temple’s Director of Estates, who has known the Church for 40 years and more. It is now a delight to welcome Paul Cutts as the Trust’s CEO, once more through the care and support of the Inns, for all that he will contribute to our work and, in this context, particularly to every aspect of the project. The project needs the construction of a formidably expert and interlocking team, to run and oversee it; and Paul’s arrival puts in place the keystone to the arch.

Ten years ago, we were able to refurbish the Church’s organ entirely through the generosity of the Inns themselves and of their members. It was a delight – and rather moving – that over 400 benefactors from within the Inns made possible the work that will last for half a century. This time we necessarily have in view a higher target for the work and a far longer timescale for its results. The stones that have lasted so well since the 1160s will be partnered with newly carved stones with a further 850 years of beauty in them.

We greatly look forward to introducing members of the Inns to the project and all that it will offer for our future. Please look out for the opportunities we will be offering, for guided tours of its hoped-for works and results. And if you see me in the West Porch, peering Holmes-like at the carvings with old photographs in hand, do request an instant summary of the transformation to come. Exciting, and commercially vital, times lie ahead.

We know that the Round Church is a small version of the Rotunda in the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem; the internal diameter of the Round (17 meters) is an almost precise and clearly deliberate one-half of the diameter of the Sepulchre’s Rotunda. And then again: at the centre of Jerusalem’s Rotunda is the aedicule, the tiny chapel built around Christ’s burial place itself. In the Middle Ages the aedicule had a porch. We should think of the Round not just as a reduced Rotunda but also as a vastly enlarged aedicule, a Tardis that had so briefly contained within its symmetrically perfect microcosm of creation the Christ by and for whom all things were created, by whom all things consist, the firstborn from the dead, in whom all Fulness dwells (Colossians 1.16-19).

In the V&A are four carved stones from the west doorway, removed in the restoration of 1840-42. They have therefore been spared both the worst of London’s pollution and all the chemical interventions of the last 180 years. They are in beautiful condition. (They have just been exhibited in Paris, as examples of 12th Century carving.) Thanks to modern imaging and 3D printing, we can create perfect models of these three voussoirs and one abacus, for the use of our sculptors in their renewal of the archivolt and jambs.

Master Robin Griffith-Jones has been the Reverend and Valiant Master of the Temple since 1999. He has co-authored and co-edited two books on the history and significance of the Temple Church in collaboration with The Courtauld Institute of Art: The Temple Church: History, Architecture, Art (Boydell, 2012) and Tomb & Temple: Re-presenting the Sacred Buildings of Jerusalem (Boydell, 2018). He is also Reader in New Testament Studies at King’s College London.