In the Old Library of Trinity Hall, Cambridge, there is a manuscript entitled Directions for beginning the study of the Law dating from the 18th Century, intended for the formation of ‘a sound common lawyer’. The author of these instructions was Sir Thomas Reeve, a former Lord Chief Justice who was Treasurer of Middle Temple in 1728. It is thought Sir Thomas directed his advice at his nephew, Edward Place who was admitted to Middle Temple in 1730-31. The Directions, which were subsequently published by Francis Hargrave in 1792, provide an opportunity for reflection both on the place of the advice in the wider setting of legal education and its literature historically and on the possible relevance of the advice for the modern study of law.

Today, law students have access to an abundance of literature on how to study law. A landmark was the publication in 1945 of the book Learning the Law, by Glanville Williams (1911-97). Now in its 17th edition by A.T.H. (Tony) Smith and published in 2020, the book has introduced generations of new and prospective law students to basic skills needed to study English law. Typical of the genre today is Sharon Hanson’s Legal Method, Skills and Reasoning (3rdedition, 2010).

The 18th Century materials attributed to Sir Thomas Reeve attest to the historical fact of the persistence of the market among students for advice about how to study law. The principal focus by Reeve is on English law – the common law and statute – training in which had for centuries taken place at the Inns of Court. The text does not focus on the Roman civil law, the historical diet for law degrees at Oxford and Cambridge, although by the second half of the 18th Century, legal study at those universities also included elements of English law.

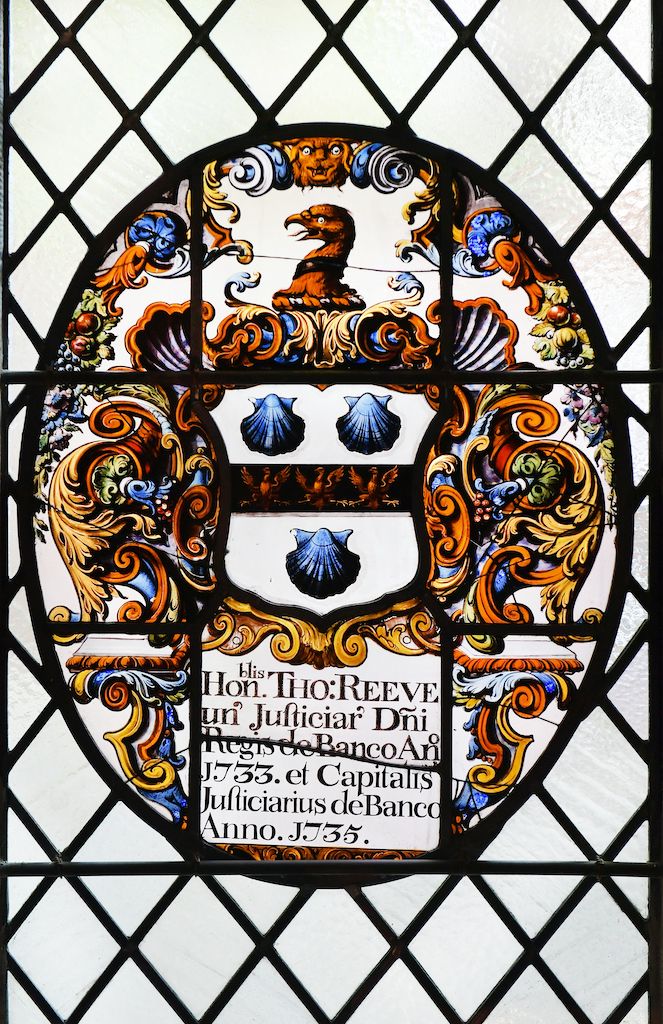

What do we know about the author of the Directions? Sir Thomas Reeve (1672/3-1737) was admitted to Trinity College, Oxford in 1688 and became a member of Inner Temple in 1690. He was called to the Bar in 1698. In 1713 Reeve migrated to the Middle Temple. In 1717 he was appointed King’s Counsel and in 1722 became Attorney General of the Duchy of Lancaster. He was elected a Bencher of Middle Temple in 1720 and in 1728 he became Treasurer. His arms are in Window 8 (North Transept) of Middle Temple Hall.

As the distinguished legal historian, Sir John Baker points out, Reeve had a busy practice in the Court of King’s Bench. An analysis of the crown-side business there in 1720 shows him engaged in more cases than any other barrister. On his appointment as a puisne judge of the Common Pleas in 1733, Reeve was made a Serjeant-at-Law (an order of attorneys with the exclusive privilege of appearing before the Court of Common Pleas and from which were drawn the judges of Common Pleas and King’s Bench). In 1736, Reeve succeeded Sir Robert Eyre (who died in 1735) as Chief Justice of Common Pleas and was knighted. However, his tenure was short-lived: he died on Saturday 19 January 1737 at his chambers in Pump Court, Middle Temple, and was buried in the Temple Church.

Reeve had been a patron of the literary arts, with several verses published in his honour. He married Annabella (or Arabella) Topham: there were no children. She was a widow who had been married to Samuel Foot(e), whose son (Topham) died aged 23; her brother, Richard, was an MP and Keeper of the Records in the Tower of London. Sir Thomas resided at Eton and at Gey’s House, Maidenhead. From a study of his will we know that Reeve kept a legal commonplace book. However, Reeve’s will states: ‘I have prepared nothing fit for the press and strictly charge and command my executors that no paper or manuscript book of mine be printed’; in a codicil he adds: ‘it is my will and desire that my executors and trustees do as soon as conveniently may be after my decease burn my Commonplace Book of the Law consisting of two large volumes’.

Reeve’s instructions concerning the study of the law, addressed to his nephew, were printed in 1792 by Francis Hargrave (1740/41-1821), a barrister of Lincoln’s Inn. Hargrave had successfully appeared for the escaped slave, James Somerset upon his application for habeas corpus and persuaded Lord Mansfield that no one could be a slave in England. Hargrave also practised at the Chancery Bar, served as parliamentary counsel to the Treasury from 1781-89, published his own opinions in Juridical Arguments (1797–9) and Jurisconsult Exercitations (1811–13), and pioneered editing legal manuscripts, such as Collectanea Juridica: Consisting of Tracts Relative to the Law and Constitution of England.

It was in the latter that Reeve’s advice on the study of law appears. Hargrave gives it the title Instructions and states that his edition was ‘now first published from a MS in the possession of the Editor’. The Trinity Hall and Hargrave texts differ somewhat: for example, as well as styling it ‘Instructions’, Hargrave inserts two footnotes, adds punctuation, italicises authors and works cited, and omits Hawkins’ Pleas of the Crown (1716). Hargrave does not say whether the manuscript he used was the one at Trinity Hall. There is, however, another copy of the Reeve advice at the National Library of Wales entitled ‘Directions’ and dated May 1744.

Neither the Trinity Hall nor Hargrave texts tell us when Reeve wrote his ‘Directions’ or ‘Instructions’. Needless to say, if Reeve wrote the advice during his tenure as Lord Chief Justice, as the title of the manuscript suggests, then we can date it to 1736-37. If he did not, and his judicial office which appears in the title of the manuscript was a later addition, from the works Reeve cites, it was written some time in or after 1732 (the date of Bohun’s Insitutio Legalis, cited in both the Trinity Hall and the Hargrave texts) and before Reeve’s death (in 1737). William Blackstone (1723-80), whose Commentaries on the Laws of England began life as a series of lectures on English law given by Blackstone at Oxford in 1753, claimed that Reeve’s instructions were an inspiration to him and formed the basis for Blackstone’s own campaign to master the common law.

The identity of the nephew for whom Reeve wrote his ‘Directions’ is not given in the manuscript at Trinity Hall, nor in the Hargrave ‘instructions’. However, in his will Reeve leaves property to ‘my Nephew Edward Place’, whom he enjoins ‘to lead a Studious, Virtuous and Religious Life’. Reeve also left him ‘all the Printed Books that are in the house where I dwell at Windsor and at my Chambers in the Temple’. The gift of books was revoked by codicil. An Edward Place was admitted to Middle Temple on 5 March 1730-31. He is described in the admissions register as ‘grandson by the sister of Thomas Reeve, Esq., a Master of the Bench’ and he was Called to the Bar on 11 February 1736-37. This would make him a great-nephew of Sir Thomas Reeve. Moreover, Sir Thomas also leaves property to Thomas Reeve, ‘the only son of my cousin John Reeve late of Birmingham, Attorney at Law’. This is the Thomas Reeve admitted to the Middle Temple on Tuesday 9 February 1740, who is registered as: ‘Thomas Reeve, relative and heir of the Right Hon. Thomas R, knight, late Chief Justice of the Bench, decd’. An examination of the students’ ledger at the Middle Temple, which starts in 1747, shows Thomas Reeve was not an active member of the Inn by that date.

Reeve’s advice on studying law is not untypical of his day; according to one scholar, ‘The eighteenth-century tradition of legal educational advice abandoned mnemonic pointers, retained commonplacing, and subdivisions without the philosophical accoutrements of Elizabethan and Jacobean Method, and was concerned above all with providing reading lists.’ Examples of these include: Roger North, Discourses on the Study of the Law (1700-30, published 1824); Thomas Wood, Some thoughts concerning the study of the Laws of England in the Two Universities (1708); Lord Ashburton’s Letter to a Gentleman of the Inner Temple, with Directions for the Study of the Law (1779); and Joseph Simpson, Reflections on the Natural and Acquired Endowments for the Study of the Law (1764) – Reeve is listed with them.

Reeve is typical in exhorting the student to keep a commonplace book, and in giving a reading list, but he seems less typical in writing about memory (and the use of general headings in notetaking) and about philosophy (the nature of law). The Directions contain propositions about how to study law and how they may be articulated in the form of principles. They may be summarised as follows (in the order they appear in the manuscript text):

(1) understand the general divisions of the law;

(2) form precise ideas for such terms as the law books do not explain;

(3) do not rely blindly on secondary literature as authority for legal propositions;

(4) observe the latitude or restrictions implicit in legal terms;

(5) draw on the experience of practitioners;

(6) use the latest editions of law books;

(7) apply the mind with ‘hearty attention’ to become a ‘sound common lawyer’;

(8) outline (or abridge) texts read and make a good note in a ‘common place’ (book);

(9) be attentive to detail, ‘sentence by sentence’, reading a text more than once;

(10) with additions and corrections make the notes ‘your own’;

(11) digest the heads of the law for use and memory;

(12) use statutes and cases for the proof of an opinion which alone is not authority;

(13) ensure commentators used ‘quote very fair’;

(14) for later study, use many books for variety;

(15) by experience you will be able to advise yourself;

(16) learn the general reasons on which the law is founded;

(17) collect leading points of the law in their natural order and as ‘generals’;

(18) always consider law as (a) a rule of action and (b) the art of procuring redress;

(19) regulate your study of the law; and

(20) render things noted easy for the memory.

The reading list Reeve recommends comprises sixteen works that straddle a range of broad periods, subjects, and genres – and they are written by jurists well-known to modern legal history.

As to periods, one is medieval (Littleton), two from the Reformation period (St. German, Rastell), three leading up to the civil war (Coke, Finch, Noy), three are from the Restoration period (Rolle, Hale, Hawkins), and seven are Georgian (Hawkins, Wood, Jacob (two), Bohun, Salkeld, Curson).

As to subjects, three are on the divisions of and general law (Coke, Wood, Bohun), three on legal terms, words, and maxims (Rastell, Jacob, Noy), one is on attorneys (Jacob), one on land law (Littleton), one on Coke (Hawkins), two on judicial decisions (Salkeld, Rolle), two are on the nature of law (St. German, Finch), one on executors of wills (Curson), one on legal history (Hale), and one is on the pleas of the crown (Hawkins).

In terms of genres: three provide detailed introductions to the whole field of law (Wood, Coke, Bohun), two are lexiconic (Rastell, Jacob), two are abridgements (Hawkins, Rolle), four are practitioner works par excellence (Jacob on attorneys, Salkeld’s reports, Hawkins on pleas of the crown, Curson on executors), and five are jurisprudential or historical (Littleton, St. German, Finch, Noy, and Hale). Needless to say, these 16 works may also be classified in other standard ways.

It was not only Hargrave who considered Reeve’s instructions valuable, in England and overseas. They were also employed by others in the 18th Century, notably by Joshua Quincy (1744-75), celebrated American lawyer and patriot, and spokesman for the Sons of Liberty in Boston prior to the American Revolution. Quincy copied Reeve’s ‘Directions’ into his own Law Commonplace (1763). He and his colleagues also encouraged their use by others.

What of Reeve today? Many of the Reeve directions would no doubt echo the advice teachers of law would give their students today: ‘provide authority for propositions of law and make sure you reference cases and statutes, rather than the textbook.’ Today’s students should also learn which texts to read ‘carefully and repeatedly, and which texts to skim read, picking out only one or two key points.’ The Reeve instructions are also notable for what they omit. Students today are expected ‘to adopt a critical distance from the law as it stands and evaluate those aspects of the law which might be described as deficient, in some way’. The modern student would benefit from further advice as to how best to sharpen one’s critical skills to this end.

Commenting on Reeve, his predecessor, Lord Thomas of Cwmgiedd, former Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales (2013-17) offered the following observations in a personal communication to Professor Doe:

I doubt whether any Chief Justice these days would give such detailed guidance, but the general tenor of the advice would be broadly similar. If such guidance were to be given today I would stress: (1) the acquisition of an overall understanding of law; (2) the necessity of getting a sound knowledge of black letter law in the basic subjects (particularly criminal law, family law, private obligations (contract, tort etc) and constitutional and administrative law); (3) finding the time to read and read again important passages in seminal texts and cases; and (4) never relying blindly on secondary sources. I was surprised that there was nothing [in Reeve] specifically about procedure, but that was then understood as essential; today it should be, but generally is not in the UK.

However, as to differences between today and Reeve’s time, Lord Thomas commented:

The differences would be: (1) adopting a critical approach to established law and opinions on that law; (2) studying other contemporary systems of law and the law in its broadest sense that is applied by other bodies (such as ombudsmen or through the lex sportiva); (3) understanding the digital revolution, its effect on the law and the way in which existing principles of black letter law can be developed to underpin it (in a way similar to the development of commercial law in the eighteenth century, but at a vastly greater pace); (4) experiencing the practical operation of the law in its social context; and (5) a grounding in the application of the rule of law and in ethics.

Books about how to study law have become a well-established feature of modern legal educational literature. They are not new. Sir Thomas Reeve’s Directions, which he wrote probably in the last five years of his life and addressed to his nephew, a student of Middle Temple, were greatly valued by his 18th Century contemporaries, including Sir William Blackstone and by the American lawyer, Joshua Quincy. Reeve’s detailed advice, articulated in the form of numerous principles, remains of contemporary relevance for students. Although the reading list Reeve recommended will be of interest mainly to legal historians, the principles on which it is based are still worthy of consideration, as much as they are capable of refinement or extension, by students who are engaged in the study of law today.

For a longer printed version of this piece for use in Trinity Hall Library, see: https://www.trinhall.cam.ac.uk/library/lessons-in-law-from-the-18th-century-to-today/

Norman Doe, LLD (Cambridge), is Professor of Law at Cardiff University where he is also Director of the Centre for Law and Religion.

Master Mark Hatcher is Reader of the Temple and currently studying for an LLM in Canon Law at Cardiff.