From Psalm 89

Let thy hand be strengthened, and thy right hand be exalted;

Let justice and judgement be the preparation of thy seat, and mercy and truth go before thy face.

Psalm 89 was the opening anthem at the coronation of King Edgar in Bath, on 11 May 973, by Dunstan, Archbishop of Canterbury.

Dunstan, in his years of exile, had encountered the coronation rituals of continental Europe. He himself had the largest part in drafting Edgar’s service. It was an imperial rite. It remains the basis for the Coronation Service to the present day.

During the service Dunstan, in time-honoured fashion, would put the ring on Edgar’s finger, gird the sword at his side, raise the crown of England and lay it on his head, give the rod and sceptre into his hands. But one part of this inheritance Dunstan changed dramatically: Earlier rites for coronation had concluded with the king’s mandate: the precepts for the new reign, pronounced by the king – already crowned – and endorsed by the people with Amen. Edgar, by contrast, must make promises to his people, and before the coronation went ahead. Right at the start of the service the king declared:

These three things to the Christian people subject unto me do I promise in the name of Christ: First, that the Church of God and all Christian people under my dominion in all time shall keep true peace; Second, that acts of greed, violence and all iniquities in all ranks and classes I will forbid; Third, that in all judgments I will declare justice and mercy; so to me and to you may God, gracious and merciful, yield his mercy, who lives and reigns for ever and ever.

Historians have found in this sequence a significance and effect far more than merely symbolic. In the covenant between sovereign and people, the sovereign must first acknowledge their own duty to do justice before any subject must offer them homage; and so the sovereign must observe that promise, in order to retain their right to that which follows on from it. The sovereign’s promise is the foundation of the coronation, not an annex to it. Such has the principle – and such, in some measure, through the centuries has been the practice – of England’s polity.

***

There are 65 international Bar leaders from more than 35 jurisdictions here today. Welcome, to you all! To London, to this Opening of the Legal Year, to this unforgettable service. There are hundreds of people gathered here who have dedicated their lives to the service of the law; and fewer than 100 who are the simple beneficiaries of your dedication. Above all, then, this morning should surely be a time of thanks. Thanks from us, the legal laity, on behalf of the millions upon millions of citizens all round the world who depend on you for our rights and liberties.

Our various traditions and practices have diverged, of course. The common law world has continued to revere the evolution of law from the Great Charter onwards; but most such jurisdictions have felt the need, as we here have not, for a written constitution. The American Founding Fathers admired our restraints upon the Executive; but feared the tyranny of the Legislature. The American Constitution followed. So too in most common law countries. And beyond: continental, civilian Europe prizes a fundamental Grundgesetz, or Diritti e Doveri dei Cittadini, the list goes on.

On the other hand, when our own law courts were at last in the 1880s moved from here in Westminster, the seat of Government, to the Strand, now our Royal Courts of Justice, the building was designed as an enormous continental Palais de Justice from a cheerful assortment of medieval centuries, the fantastical skyline inspired by manuscript illuminations, the Great Hall by the Salle des Pas Perdus in Paris. We are all of us, wherever we serve, cords in the same rope, forever interwoven, drawing our strength from each other and lending our own strength to each other in times of need.

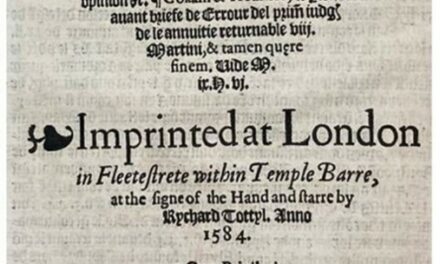

(The Law Courts were built on the site of the Knights Templars’ jousting-ground, Fittescroft. Rather a fitting ancestry.)

And we do still of course have our distinctive coronation.

Through many succeeding centuries after Edgar, the work of justice and of mercy indeed lay personally with the sovereign. The king had enormous legislative, executive and judicial power, not least in his almost untrammelled power of patronage.

But the king no longer has this power. The promises that His Majesty made here, this summer in his own name, he does not have the power in his own person to discharge. That is for his agents. You, the judges and silks of this country, serve in the king’s name; the king took his promises in yours. The weight of those wonderful robes and ancient regalia rests on his shoulders; the discharge of his oath to maintain justice and mercy, on yours.

And for it, we – all of us – owe you enduring, heartfelt gratitude.

And in particular, here in London, on this whole morning of Thanksgiving we have two special thanks to give. For six years Lord Burnett has served as our Lord Chief Justice. Turbulent times, all navigated with imperturbable good grace: the endless need for greater resources, yes; but most dramatically in 2020, at the first lockdown, Lord Burnett led our whole court system online within days. On all sides it is said, Lord Burnett, that we all owe you more than we will ever know for your work with government and with jurists all over the world. And perhaps most important of all, you are – as was said at your Valedictory – ‘admired, respected, perhaps loved would be a better word’. Thank you, from us all, for the last six years.

This morning Lord Burnett’s successor, Lady Chief Justice Carr, took her oath. The first woman to hold this great office. Lady Carr is well known to many of us, hugely admired by all. Lady Carr, we give thanks for your appointment, for all the work that will follow. Whatever our own traditions, we pray, Lady Carr, for God’s wisdom upon you; and we pledge ourselves, all of us, to support you through the years to come as we know that you will, year after year, support us all, in this country and beyond, in the rule and practice of the law that we hold dear.

Let thy hand be strengthened, and thy right hand be exalted;

Let justice and judgement be the preparation of thy seat, and mercy and truth go before thy face.

***

On Saturday 6 May this year, His Majesty King Charles III processed into Westminster Abbey for his Coronation. Here, in the theatrum of medieval coronations, stood two thrones. Both faced the altar, the place of God himself, the source of the King’s office and authority. To the east, the ancient Coronation Chair. Slightly to its west, and right under the crossing, the central stage realised at the great coronation cathedral of Reims and then here: the Throne of Homage.

But at his entry His Majesty sat in neither: Their Majesties must first sit to one side, on the Chairs of Estate, across the sacrarium.

For before His Majesty could receive his regalia, his crown, the anointing oil, his place as king, he must make his oath. As 1,050 years ago – almost to the day – in Bath, and at every Coronation since, the sovereign must first make his great promise to his people. The king laid his right hand on the Bible.

Archbishop of Canterbury: Will you solemnly promise and swear to govern the Peoples of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, your other Realms and the Territories to any of them belonging or pertaining, according to their respective laws and customs?

The King: I solemnly promise so to do.

Archbishop: Will you to your power cause Law and Justice, in Mercy, to be executed in all your judgements?

The King: I will.

Master Robin Griffith-Jones has been the Reverend and Valiant Master of the Temple since 1999. He has co-authored and co-edited two books on the history and significance of the Temple Church in collaboration with The Courtauld Institute of Art: The Temple Church: History, Architecture, Art (Boydell, 2012) and Tomb & Temple: Re-presenting the Sacred Buildings of Jerusalem (Boydell, 2018). He is also Reader in New Testament Studies at King’s College London.