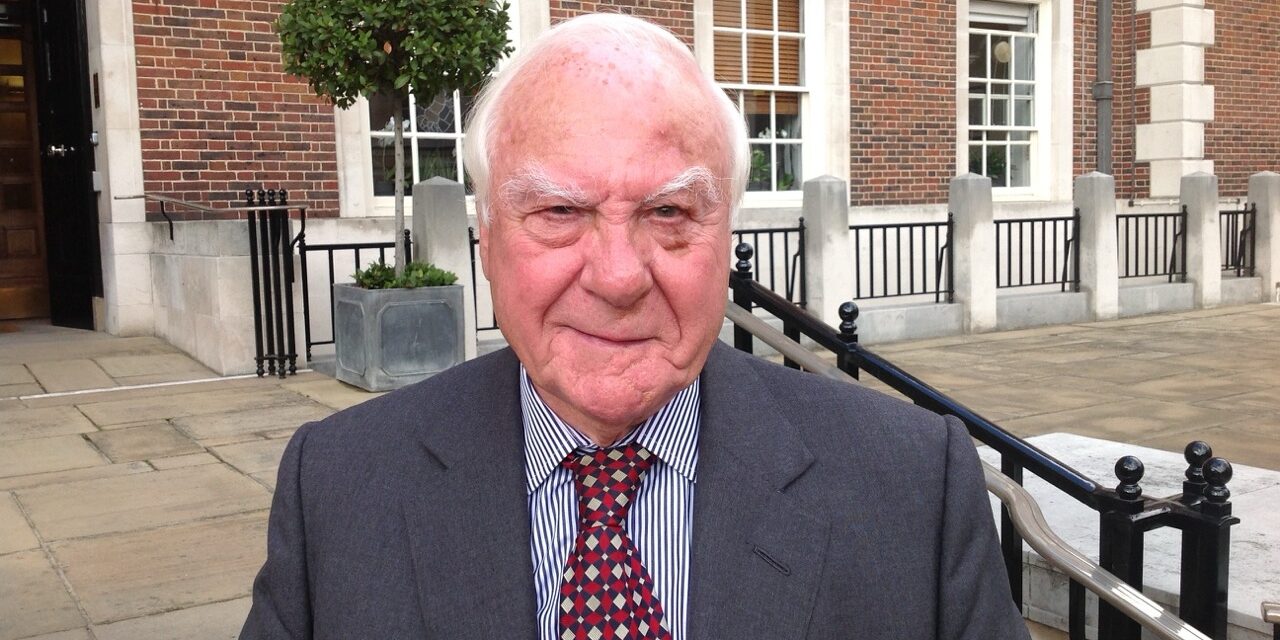

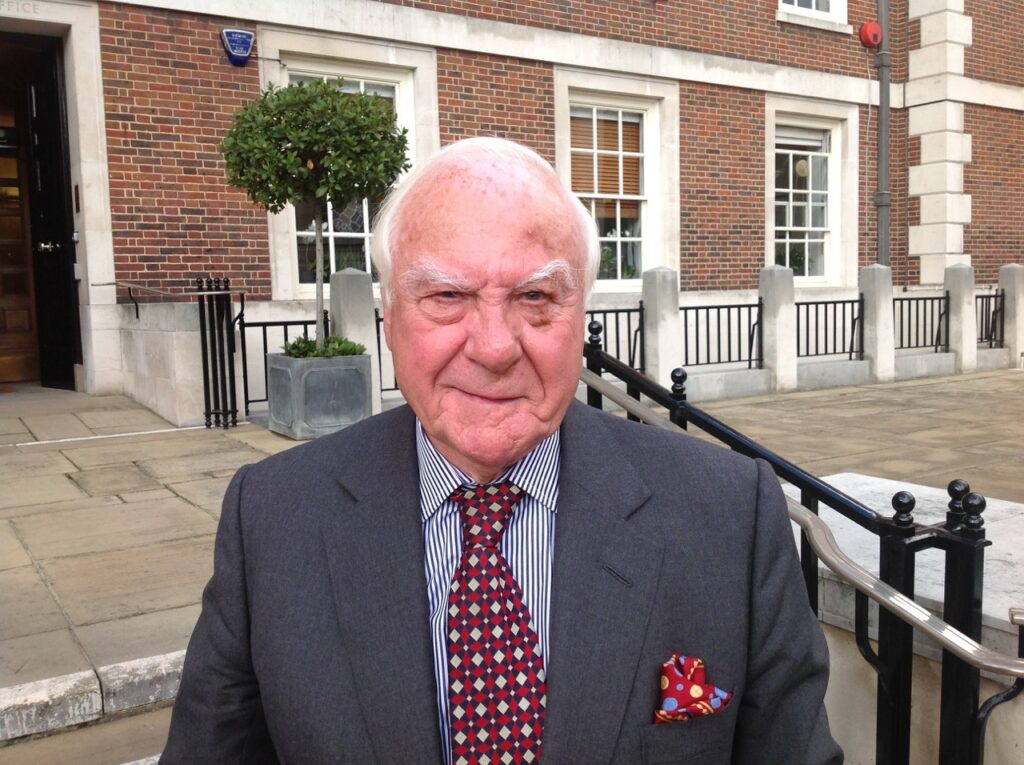

Christopher Benson might have played international rugby and had a naval career but for a serious car accident when he was 20. After a party he was driving two friends back to what is now RAF Lossiemouth near Elgin in Scotland when he rounded a bend at speed and slammed into a pile of rubble blocking the road.

The passengers were thrown clear, but the car landed on Benson. ‘I started crawling,’ he said. ‘I couldn’t walk. Everybody told me I was drunk, but I was not.’ He had multiple skull fractures, a collapsed lung, temporarily lost the sight of one eye and was deaf in one ear — and when he woke up in hospital, he realised that his face had been disfigured. His mother did not recognise him. He had two years of operations under Sir Harold Gillies, a leading plastic surgeon who made Benson watch the final procedure in a mirror. ‘It made me feel very humble,’ he said.

Instead of the navy he went into real estate and rescued MEPC, Britain’s second-largest property group, from the 1974 financial crash. He also chaired the London Docklands Development Corporation, launching Canary Wharf and Transport for London’s Elizabeth Line, expanding the Royal Opera House in Covent Garden and heading the Housing Corporation, the retailer Boots and the insurer Royal Sun Alliance. He worked 13-hour days, six or seven days a week, travelling the world to inspect far-flung projects. Another property entrepreneur, Trevor Osborne, said: ‘I sometimes thought he would have liked to be chairman of everything.’

Benson’s outward charm led some to mistake him for a soft touch, but he described himself as ‘not a very warm person, not very loveable’ and was not shy of making enemies. During a long feud over Crossrail he labelled Alistair Darling ‘secretary of state for indecision.’ Darling later sacked him. ‘I’m not patient with the people that matter and perhaps I’m over patient with people that matter less,’ Benson said. ‘I spend a long time listening to the problems of people I don’t love and then expect too much of the people I do love.’

The Egyptian businessman Mohamed Al Fayed invited him to lunch at his Park Lane office to offer him the chairmanship of Harrods, the Knightsbridge store that Al Fayed had recently bought. When his host made it clear that the waitresses were available for sexual services Benson said, ‘I think I’m in the wrong place,’ and promptly left.

Christopher John Benson was born in 1933 in Wheaton Aston, Staffordshire, north of Wolverhampton, the only son of Charles Benson, a dentist, and Catherine (née Bishton), a nurse. Under the red glow of wartime incendiary bombs falling on Birmingham, Christopher attended Hallow primary school and, after failing grammar school entrance exams, the King’s School Worcester. ‘I played rugby and truant,’ he said. ‘Looking back, I am cross with myself for not using the brain God had given me.’ Yet he played the bugle in the school band, became a county champion swimmer and excelled at boxing, diving and water polo. An ex-navy teacher pointed him towards the Royal Navy.

He failed entry to Dartmouth naval college and joined the Incorporated Thames Nautical Training College ship, HMS Worcester, at Greenhithe on the Thames, where he was beaten on his first day for walking instead of running. He went into the Merchant Navy at 16 and travelled the world on the Union Castle line’s Rochester Castle. After National Service — naturally, with the navy — he was posted to Lossiemouth, then a Fleet Air Arm base, where he played rugby for the Royal Navy Scotland and but for his accident was in line for an England trial.

Invalided out, his father found him a job as a trainee auctioneer. After one auction he was left with half a dozen unsold pigs, which he turned into a business with a 100-strong herd. He met a surveyor who recommended him to Arndale Developments, which built shopping centres.

At the 1957 Salisbury Fair he met the city councillor Jo Bundy and joined the local Young Conservatives to see more of her. They married in 1960 and lived in the house in which she was born. She became mayor of Salisbury and worked for several charities, mainly for cancer research and the elderly. ‘I was a bit frightened of her,’ Benson said. ‘She was “establishment” and I was not. It was quite a job to get her to marry me, but she has been the greatest influence in my life.’ Jo predeceased him in 2022. Their two sons, Charles and Julian, both barristers, survive him.

In 1969 Benson started his own firm, Dolphin Developments, and was so busy he obtained a pilot’s licence and bought his first plane in 1970, followed by a helicopter three years later. In 1973 he sold his company to Law Land and was hired by MEPC as development director. He and David Davies, a co-director, travelled the world persuading banks to back the company. After two years he became managing director.

As chairman of the Civic Trust, he championed high-quality architecture and raised the money to renovate Sir John Soane’s Museum in London. He also served as president of the National Deaf Children’s Society. He was knighted in 1988 for public service. In 2005 he was appointed an honorary citizen of Corfu, an island he loved.

‘If something needs to be done,’ he said, ‘I’ll try to do it. I am determined, but not in that sort of boorish, push-people-out-of-the-way sense. I don’t mind if everyone else comes with me, it’s quite fun if they do, but I am determined to get there whatever.’

Reproduced with kind permission from The Times.