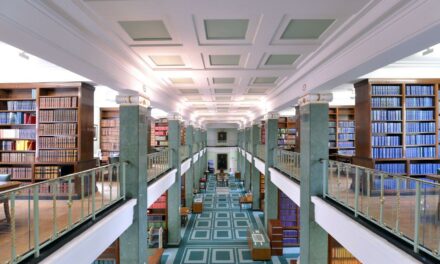

During February to April this year, the Library held an exhibition on the Evolution of the Law Report. At first glance the law report does not seem the basis for a very dynamic exhibition, but that may in part be due to our over exposure to this document – law reports are frequently requested items, and their everyday usage almost makes them disappear into the background. We have a tendency to forget how crucial a document the law report is. Not all cases set precedents, but when they do, the law report is what enshrines that legal change, making it a powerful document and worth a closer look.

Law reporting begins in the latter part of the 12th Century, one of many pivotal legal innovations of the period. It was during this time that somewhat of an overhaul happened in the legal world, with administration of justice moving away from local practice to centralised and systemised operations. This included official record-keeping of court decisions, allowing for the tracking of cases and establishing consistency in legal procedure, ultimately leading to the common law system as determined by judicial precedent.

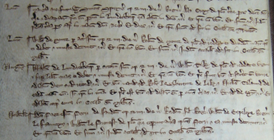

Early record-keeping took place within rolled-up sheets of parchment, or rotuli, which were sewn together in chronological order. The Plea Rolls collated all the pleas heard during a legal term and a new roll would be produced within each of the four legal terms. Unlike later law reports, the Plea Rolls did not record what was said in court, but rather the processes and outcomes.

Though the judgements were written in a standard format, there was ample room for improvement. Changes that appeared in the Plea Rolls were such things as the introduction of numbering of sheets and authorial attribution, which seem small, but imagine trying to locate information in a Plea Roll without a page number reference or the name of the clerk who recorded the case. They are a good example of necessity driving change.

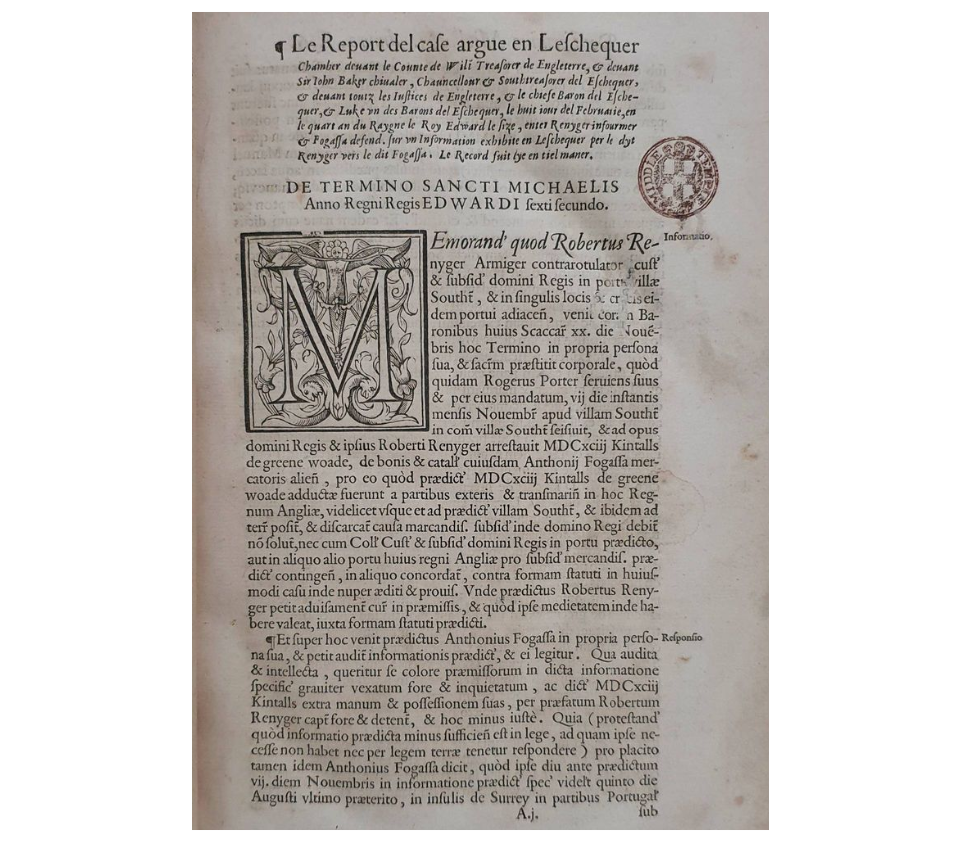

The Year Books, which were transcribed from the Plea Rolls, were written in Anglo-Norman French and contained anonymously written notes and judgements on cases from the Norman period to the Tudor age; you can find references to the original rolls in the margins of the printed volumes often notated as rot., short for rotuli, as well as the legal term for the particular roll.

Though not as sophisticated as modern law reports, the Year Books provide much insight into the most formative period of the common law. Some of these cases were deemed important enough that reporters would publish them under their own name. It is in these publications and subsequent reprints and translations that we can find the Year Books.

It is unclear why they were transcribed or who oversaw the effort, but consensus seems to be that it was the work of law teachers and students. The Year Books do not aim to offer precedent, rather their aim seems to be to offer instruction on how to argue a case, which certainly fits the theory that they were study aids.

One does wonder though if students may have been used to transcribe, not only in order to further their learning, but also to parse information in the rolls for anything of interest. Middle Temple Library often facilitates internships and some of the work of the interns is focused on the transcription of cases from manuscripts of private notes.

One such manuscript is featured in our exhibition, Notes of cases heard at the Old Bailey, 1765-1769 (you can read about the experience of our intern Jack Alphey in a blog post and consult the index produced as a result of his research). Our aim is to offer our interns a chance to work with rare materials and to contribute to the wider knowledge base of case law. We are certainly not pioneers in this respect.

Whatever the reason for the transcription of the Year Books, they would be the first to benefit from a piece of new technology invented in the 15th Century. William Caxton happened upon a printing press in 1473, while on a trip to Cologne. For him it was a solution to a personal problem; he had been translating a long poem on the Trojan wars, and the only way to share it with friends was to make copies by hand. Caxton would introduce the printing press to England as well as publish the very first printed book in English, Recuyell of the Historyes of Troye.

The legal world did not immediately warm to the idea of printing law reports. The Inns of Court had an established oral tradition of education, one that encouraged learning through observation, through the performance of mock trials, and discussion with peers. The latest case law was shared through circulating manuscripts, but access was locked down to select individuals. If you wanted to get past the paywall, you needed to be part of the right friendship group.

There was an anxiety around the value of knowledge as printed and available for all to see, versus something shared verbally and held within the confines of the mind. It would be a while before printing was accepted as an innovation for good, but in the meantime, between clerks wanting to make some money and an obvious gap in the market, manuscripts of cases found their way to the printing press.

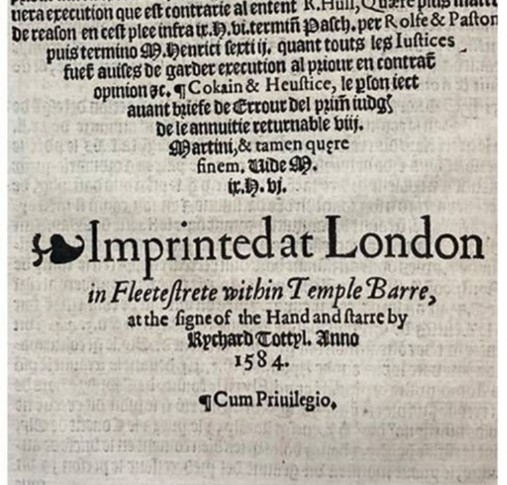

Early legal printing would be dominated by the publishing of Year Books, bringing to light the early development of the common law. Richard Tottel, whose works feature in our exhibition, was responsible for printing over two hundred issues of Year Books alone. We were quite keen on Tottel as he carried out his business from his shop at the Signe of the Hand and Starre on Fleet Street, near Temple Bar, only a stone’s throw from where we sit, providing us with another glimpse into the history of these environs.

Tottel was granted two seven-year patents, one after the other, the second by Elizabeth I, which essentially allowed him to be the sole publisher of common law legal works until his death in 1594. And he did not just print, he brought innovation through better citation and standardisation with such things as numbering of leaves in a book and numbering of cases, as well as the use of abbreviation for adding cross-references, contributing towards a more standardised document.

Strangely enough he would be better remembered for his printing of an anthology of poems, Songes and Sonettes, or Tottel’s Miscellany, published in 1557, an expensive venture which, luckily for Tottel, was a Tudor hit. His Miscellany may be the more memorable of his publications for its impact on Elizabethan verse, but he also undeniably leaves an indelible imprint on the history of law reporting.

A short period after Tottel’s death, the patent to print would be dissolved and anyone could print common law materials. The downside of this is immediately obvious, but it did mean the publication of a large and diverse body of work. Volumes of written manuscripts would continue to circulate, whilst the debate around the merits of printing and the printing itself continued. Lawyers began to get in on the action in what seems a somewhat embarrassed fashion (education at the Inns must have made them familiar with Socratic thought on the value of knowledge against mere inventions for remembering).

A good thing too, as this would see the emergence of the big law reporters, the real standard-bearers who would inspire expectations about what counted as reliable law reporting. After the Year Books, it was these reporters who would create the next shift with the production of what we now refer to as the nominate reports. The nominate reports are known by the names of the reporters who published them and hundreds of these reports would be published between the 16th Century and 1865. If you’ve been to the Library, you will have seen some on the open shelves.

Though there would be many reporters, the ones who would become synonymous with quality and reliable reporting were the likes of James Dyer, Edmund Plowden, and Edward Coke. Quality was certainly not restricted to these three men, but they are notable for their contribution towards a more reliable and authoritative form of document. Plowden’s reports especially raised the bar, commended for their accuracy. He also included transcriptions of cases with critical commentary on arguments, elevating the law report above mere record-keeping. This former Master Treasurer of Middle Temple was the first law reporter to have his reports published during his lifetime.

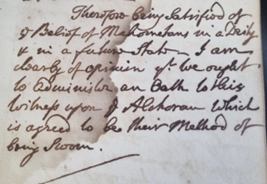

While structure and form were evolving, so was the language of the law. The Plea Rolls had been written almost entirely in a highly abbreviated form of Latin. Norman Conquest brought with it a French speaking court, which introduced more lingual influence. From this emerged Law-French, which can be found in early law reports, a strange mishmash of French, Latin and Anglo-Saxon, difficult to decipher even by fluent speakers of French. Though English wouldn’t become the official language for both pleading and writing in court until 1730, the odd report was still published in English before that, and 1641 saw the first law reports printed entirely in English, an early step in the direction of the language of the people and the language of the law finding alignment.

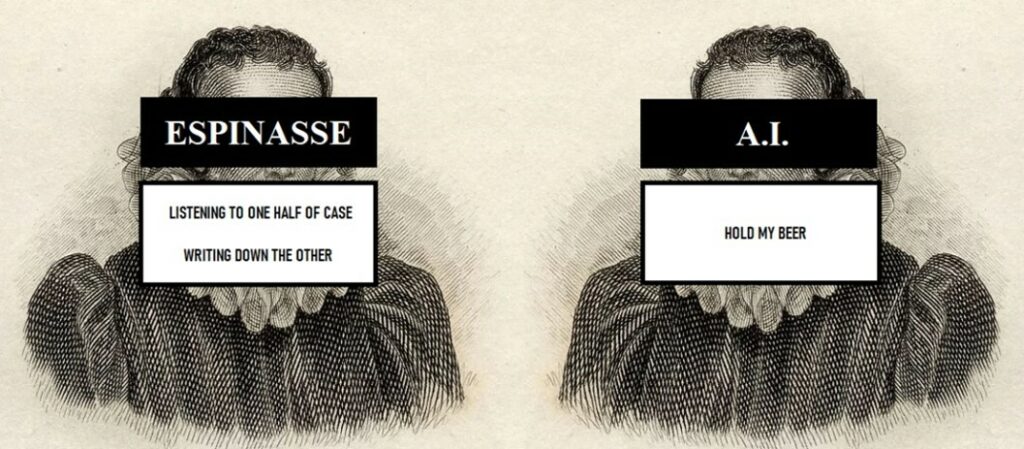

Between the efficiency of the printing press and the freedom to print without patent, the mid-seventeenth Century saw a surge in the publishing of law reports. But as quantity increased, so diminished quality. There was a lot of room for inaccuracy with reports being falsely attributed, published posthumously, anonymously, and years after they were adjudged – a big problem in a legal system that relies on precedent. Some reporters were known for being unreliable, with judges publicly criticising them and even forbidding the use of certain law reports in court. Isaac Espinasse was one reporter who received criticism for his reports. Pollock C.B. wrote about him that he ‘heard one half of a case and reported the other’ ((1938) 54 LQR 368).

Frustration with such lack of standards would come to a head in 1864 with a meeting of the Bar at Lincoln’s Inn. The result of this meeting was the founding of the Incorporated Council of Law Reporting (ICLR) in the following year. The ICLR would be composed of members of the Inns of Court and the Law Society. Law reporting was to be standardised and divided into just 11 different series, which later became six following the reorganisation of the courts. There would also be guidelines on what a law report should contain.

With the establishing of the ICLR and its standards for law reporting, 1865 can be considered the birth of the modern law report. The biggest changes since then really have been around modes of access, first with the age of the computer chip, and then with advent of the Internet. The computer age has allowed for the digitisation of law reports and wider access, but that access is limited to those who can afford the high prices. However, where there are paywalls, there are also initiatives that work to free up access to law, British and Irish Legal Information Institute (BAILII) being a good example (not to mention ICLR with their free WLR Daily Reports – do check out their lovely review of our exhibition).

Throughout this exhibition, we have understood the evolution of the law report to be comprised of changing form, structure, language and access, shaped by requirement, boosted by technology. The next evolution is hard to predict, but with artificial intelligence being lauded as the next big thing, we can assume the law report might also benefit (or suffer) as a result of this advancing technology. Already AI has delivered by not even waiting to transcribe cases and just going ahead and making them up from scratch, so who knows what wonders lie ahead in the realm of future law reporting.

Resources

Anglo-American Legal Tradition

British History Online: Court of Common Pleas

Imprinted at the Signe of the Hand and Starre: Richard Tottell and Sixteenth Century Legal Citation

National Archives at Kew: Records of the Court of Common Pleas and other courts

Using the Year Books to find Old Case Law

Emma Manktelow

Emma is one of three Assistant Librarians and oversees the management of the European collection. She has a background in university law libraries and previously worked in the collections development team at the House of Lords Library. She joined the Inn in 2022.

Harpreet K. Dhillon

Harpreet is the Deputy Librarian and oversees the cataloguing, classification and library management system. She is an English Literature graduate and previously worked at Guildhall as part of the City of London Libraries’ Bibliographical Support Section. She joined the Inn in 2016.