The year 2022 marks the centenary of the first Call to the Bar of women at the Inns of Court, and the achievements of female pioneers in the legal profession have been widely celebrated. However, prior to the admission of women into the profession, they were still a part of the life and culture of the Middle Temple, though with far less visibility. As a result of the dominance of men in the administration of the Inn until the 20th Century, there are very few archival records relating to women prior to this time, and when they exist, they are usually written from the perspective of men. Despite the limitations of the records, it is still worth examining the role of women at the Inn and attitudes held by the administration and members towards them.

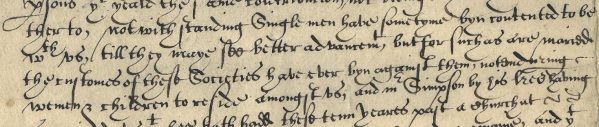

In 1903, when considering the application of Miss Bertha Cave to be admitted as a student to Gray’s Inn, the Lord Chancellor stated that ‘nobody ever dreamt that a lady would ask to be admitted to the Inn, or there might have been rules on the subject’. The concept of women entering the profession was so outrageous, that restrictions on their admission were never explicitly created, but there were other restrictions placed on the presence of women at the Inn over the centuries. The first example of this can be found in a letter to King James I, written by the Treasurers of the Middle Temple and the Inner Temple on Monday 13 May 1613, regarding the recommendation by the King of Alexander Simpson for appointment to the position of Lecturer. In it they state that ‘…single men have some time been contented to be with us till they may see better advancement, but for such as are married the customs of these Societies have ever been against them, not enduring women and children to reside amongst us’.

Until around 1650 there is no evidence that gentlemen flouted the custom that forbade the residence of women and children in chambers. From Tuesday 24 May 1650, however, orders start to appear in the Minutes of Parliament demanding the removal of families. One instance of this can be found in a minute dated Tuesday 2 June 1654, which orders that ‘all women and families shall remove by Thursday 8 June’. It is clear that this order was ineffective, as another was issued on Wednesday 24 June 1654 stating that ‘Any one permitting a woman to lodge in his chamber after Michaelmas, shall forfeit it ipso facto’. By November of that year, the Benchers were obviously getting frustrated by the refusal of members to abide by their restrictions, as they issued another order stating that ‘All persons. . . who shall not remove their wives women and families before St. Thomas’ day, shall be expelled, and the chambers be forfeited’. Despite the seriousness of the penalties, members persisted in keeping wives and families in their chambers and orders continued to be issued prohibiting them until around the 1730s.

On Monday 15 April 1737, a comprehensive survey was commissioned by Parliament to establish the number of family members of tenants that were living in chambers of the Inn. The resulting data reveals that there were 72 family members living in chambers, 20 of which were children. It appears that this survey may have heralded a turning point in the Inn’s attitude to women and children. By Monday 23 November 1744, a Porter was allowed to keep his wife in his rooms in Pump Court, contrary to an order of Thursday 1 May 1727 that ‘no officer of the House shall keep a family in any Chamber in the House’. By the early 19th Century this change in attitude was fairly explicit. An order of Parliament of Friday 23 January 1807 relates to two gentlemen with large families lodging in their chambers. The chief complaint of the Society was that they were throwing large quantities of filth and soil from the windows, rather than objecting to their presence in general – they would be allowed to remain if they ceased causing a nuisance.

The Society’s dislike of women residents did not preclude them employing them in menial roles. A comprehensive report produced regarding the Middle Temple during the reign of King Henry VIII indicates that at this time the Inn employed a laundress as its sole female servant, and that the duties of the laundress were washing the clothes of the house. The employment of women at the Inn expanded to include a female dishwasher in the 1660s. Laundresses continued to be responsible for cleaning the table linens throughout the 17th Century until the name of the role changed to ‘washerwoman’ in the 18th Century. At this time, a distinction opened between the role of ‘washerwoman’ and the role of ’laundress’, which evolved to encompass the job of a cleaner – in 1738 the Inn began to employ a separate woman, Elisabeth Martin, for cleaning the Library and Parliament Chamber under the job title ‘laundress’.

The Inn directly employed a few women, but more found employment from tenants within the Temple precinct. Laundresses were employed to clean chambers and complaints against them were often brought before Parliament. A recurring problem, brought to the attention of Parliament in one instance on Monday 31 May 1717, was that laundresses ‘…throw out of the window, filth, and empty slops, stools, and other nastiness in the several courts of this Society’. They were also in the habit of creating fire hazards by carrying coal ashes down from chambers and leaving them in lower corridors and cellars. On one memorable occasion in 1720, many of them had managed to obtain keys to the garden to gain access to the water pipe there, and were accused of breaking the pipe and cock, which caused the garden to flood. After this incident, access to the keys was restricted to the gardener.

The Middle Temple welcomed the respectable employment of laundresses and washerwomen, but there was one class of women that was completely unwelcome – so called ‘lewd women’, or prostitutes. The primary method that the Inn used to discourage them was by restricting the entry of women after a certain hour. To prevent the discrete transportation of such women in and out of chambers, a ban on Hackney coaches within the gates of the Temples after 11 o’clock at night was proposed in 1714. Restrictions put in place did not prevent members from attempting to flout the rules, and this led to violence on several occasions. A complaint submitted to Parliament by the Chief Porter in 1717 states that he attempted to refuse entry after 12 o’clock at night to a Mr Mark Hill and an accompanying woman. As a result, he was insulted and beaten by the gentleman. He made the same complaint against two other gentlemen a couple of weeks later.

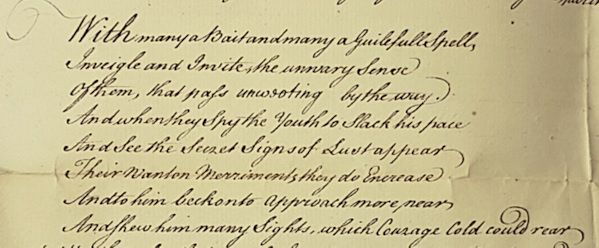

Despite the violent actions of some members, a large proportion of the membership officially declared such women an unpleasant temptation. A petition was submitted to Parliament in the late 18th Century by barristers and students requesting that an additional watchman be appointed to attend all night at the wicket of Devereaux Court to save the barristers from the place where ‘Circe her nocturnal revels keeps administering her poisoned cup… her votaries those evil things that walk by night in trim disguise, fair in appearance only foul within, empty of every good, yet blythe and gay’. The petition begged the Benchers to ‘remove us from these objects that with shame we must confess have sometimes created pleasure, but oftener pain’ and stated that the additional watchman would help them ‘turn away from the hitherto unavoidable Road of Impurity and Disease’. This wording implies that although these young barristers protested their distaste of prostitutes, it is probable that they regularly availed themselves of their services.

For much of the history of the Middle Temple, the presence of women was discouraged. The Inn allowed their employment in menial and traditionally feminine professions. Until the 18th Century, there were heavy restrictions against even traditionally respectable wives lodging within chambers of the Inn and prostitutes were seen as objects of temptation leading otherwise respectable men astray. There was very limited progress towards equality between the 16th-18th centuries, with women eventually being allowed to lodge in chambers, but it was still a long road before they would become an accepted presence within the legal profession.

Victoria Hildreth first joined the Inn as Projects Archivist in 2017, before becoming Assistant Archivist in 2019. She brought experience in the management of historic collections from her previous position at the V&A Museum Archive of Art and Design and has volunteered as a Historical Interpreter for various organisations since 2010.