The Inn’s long history is interwoven with rich and varied royal associations, having played host to visits from countless monarchs, celebrated royal jubilees, and often been subjected to scrutiny from royal authorities and occasionally from monarchs themselves.

These connections, in fact, pre-date the Inn itself. The Temple, as the London headquarters of the Knights Templar, played an important role in the crisis of 1213-1215. During this period, King John based himself here, and it was the setting for many of the negotiations that led eventually to the Magna Carta, as well as a treasury for much of the King’s wealth.

Later, several monarchical decisions led to the establishment of the Middle Temple. The King of France, envious of the wealth of the Templars, persuaded the Pope to abolish their Order in 1312, and those in London were dispersed into other orders. King Edward II, who took control of the Temple Lands, eventually passed it to the Knights Hospitaller, who, already based at Clerkenwell, had no need for the land themselves. Not much later, the royal court moved permanently to London, thus leading to an influx of lawyers in need of a convenient base in the capital – and the vacant chambers, cloisters and Halls of the Temple fitted the bill perfectly.

The Inn’s earliest records date from 1501, and the Minutes of Parliament during the Tudor period illuminate how much royal attention was paid to the Middle Temple, which by this point had swelled in social, cultural, and political prestige and importance. Our associations with Elizabeth I are well-known, their most notable reminder today being her reputed gift of the High Table. The Queen is known to have visited the Inn shortly after the completion of the new Hall in the 1570s, a construction project overseen by Edmund Plowden, himself a royal favourite, despite his staunch Roman Catholicism.

Despite this warm relationship, the religious tensions of the age were nonetheless acutely felt. Agents of the crown cast their suspicious gaze over the Inn, fearful that sanctuary and even support were being offered for Catholic subversion. Surveys were undertaken reporting on religious affiliation within the Inns, allegations were made that the Middle Temple was ‘pestr’d with papists’, and the Catholic Under Treasurer, Thomas Pagitt, was eyed with suspicion.

The Stuart monarchs were no less assiduous in their scrutiny. In 1614, King James issued a set of ‘Orders for the reformation and better government for the Houses of Court’, which covered a diverse array of matters including ‘harbouring ill subjects or dangerous persons’, disorders at Christmastime (a perennial concern), the wearing of cloaks, boots and spurs in Hall, and the showing of ‘due reverence and respect’ to the Benchers by the younger members of the Inn.

James’ son, King Charles I, was similarly preoccupied. Four letters from Charles to the Inn’s Benchers survive in our archive which illustrate well the concerns of the age, and certainly those of the King himself. One of these notes that, as ‘these times are full of action and danger, true religion being now assalted in all parts of Christendome’, the King wishes all his subjects to be well-prepared by exercise of arms to defend the Kingdom. He commends the members of the Inns to turn their hand to the exercise of archery, arms, and horsemanship – though he is careful to note that he does not wish that ‘the students of our lawes should by this occasion neglect their studies’.

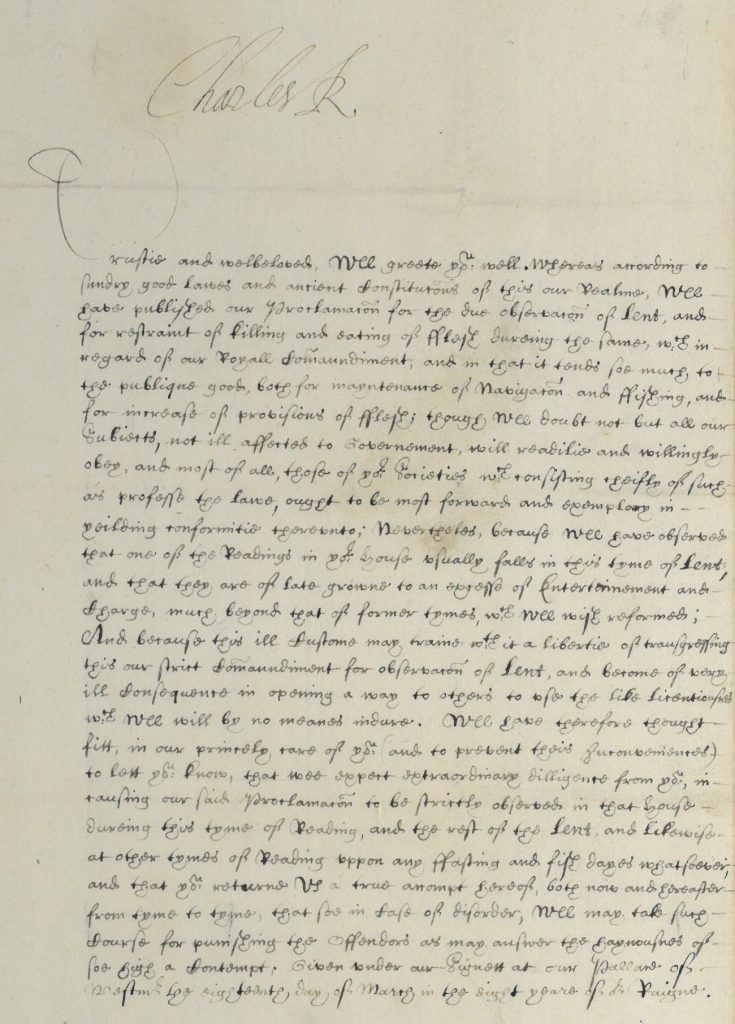

The Lent Reading, then a more extended period of educational feasting than it is today, grew to such a pitch of revelry that it drew the opprobrium of the King. He wrote to the Benchers in 1631, reminding them of a recent proclamation for the observation of Lent and the abstinence from meat during the period, and noting that the Reading which fell in this period of fasting had ‘of late growne to an excesse of entertainment and charge, much beyond that of former tymes’. He expressed his wish that the Benchers ensure observance of his proclamation.

However, it wasn’t all religious strife and micro-management. The Inn was involved in the staging of two notable masques (a form of courtly entertainment encompassing music, singing, and dancing, and the performance of allegorical and exotic narratives by a mix of professional actors and courtiers) for the Royal Family in the first half of the 17th Century. The first, in 1613, was put on by Middle Temple and Lincoln’s Inn to celebrate the marriage of King James I’s daughter, and featured scenery and decorations designed by the leading contemporary architect, Inigo Jones.

Some years later, to celebrate the birth of King Charles I’s second son, the future King James II, another masque was staged, by all four Inns, entitled ‘The Triumph of Peace’. This was funded by members, and surviving orders of payment paint a fascinating picture of the event, particularly of the masquers’ costumes. Purchases included Florentine satin, white taffeta, priests’ habits, plumes, roses, ‘buskins’ (boots), feathers, ‘vizards’ (masks) and silk stockings. Props included truncheons, chariots and (with evident lack of regard for fire safety) over one thousand torches, and one Thomas Basset was paid 200 shillings for ‘playing the bagpipes and Jewish harp and making bird songs’. It must have been quite the spectacle, and the King was so impressed that he invited 120 Innsmen to enjoy his own upcoming masque.

At the outbreak of the English Civil War in 1642, the Inn was divided between the Royalist and Parliamentarian camps, and several notable Royalist Middle Templars fled London to join the King at Oxford. These included Sir Richard Lane, who entrusted his library and possessions at the Inn to Bulstrode Whitelocke, a Parliamentarian. In 1643, many Royalists (including Lane) found their property confiscated by Parliament – a total of 102 members of the Middle Temple and the Inner Temple had their chambers seized in this way.

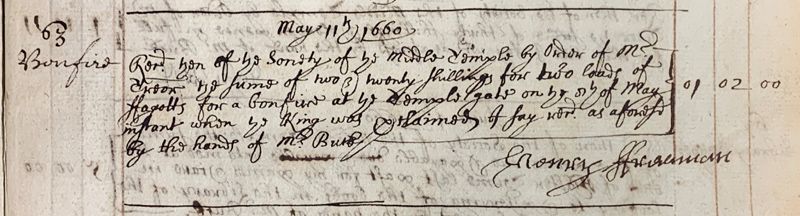

While the Inn spent much of the interregnum in Parliamentarian hands, with many traditional activities and entertainments curtailed and even outlawed, an abrupt change in mood is apparent at the Restoration of the Monarchy in 1660. The first sign of this is a receipt from Tuesday 8 May 1660 ‘for a bonfire at the Temple gate … when the King was proclaimed’: Parliament had that morning issued a proclamation, read at Temple Bar, that Charles II was King. This was just the start – on Charles II’s arrival into London and procession through the city, a wooden scaffold or stand, hung with banners and tapestries, was erected at the Temple Gate from which members could spectate. Similar celebrations marked the coronation the following year, and the Inn also commissioned a marble bust of the King.

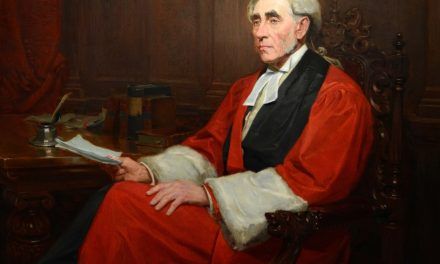

Not many years later, three royal portraits were acquired and hung as a centrepiece above High Table in Hall. The painting of King Charles I was painted after an original by Anthony van Dyck in the Royal Collection, and was acquired, along with the portrait of James Duke of York, for £30 in 1684. The portrait of Charles II entered the collection around the same time, and the portraits of King William III, Queen Anne, and King George I were all commissioned by the Inn during those monarchs’ reigns.

The Georgian Kings did not pay such close attention to the Middle Temple – although George III is known for his dislike of lawyers, once describing the Inns of Court Volunteer regiment as ‘The Devil’s Own’. Queen Victoria’s accession to the throne and coronation are not mentioned in the Inn’s records, but a letter from an anonymous member to the Benchers in advance of her marriage to Prince Albert expresses the hope that they would not repeat their ‘discreditable “doings” at the time of the Coronation’ – the Inn, presumably, having failed adequately to mark the occasion. Things had evidently improved by 1897, when Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee was marked with a grand dinner in Hall, and the planting of four mulberry trees around the fountain in Fountain Court, two of which survive today.

The Inn maintained a close relationship with Victoria’s eldest son, Albert Edward. As Prince of Wales, he was made the Inn’s first Royal Bencher 1861, on the same day opening the newly built Library. He kept up his connection with the Inn, dining many times in Hall, still attending Grand Day dinners as King, and serving as Treasurer in 1866. Two portraits of him are on display in the Inn: one of him in his Bencher’s Gown on the Library staircase, and one on loan from the Royal Collection which hangs in the Parliament Chamber.

One of the prizes of the Inn’s silver collection is the ‘Year of the Three Kings Mazer’, a bowl produced by the master silversmith Omar Ramsden and given to the Middle Temple by Lord Rothermere in the late 1930s. Made in 1937, it bears the heads of George V, Edward VIII and George VI, all of whom were King of England in 1936, as well as those of Queen Mary, wife of George V, Queen Elizabeth, wife of George VI, and the latter couple’s daughters, Princess Elizabeth and Princess Margaret.

Queen Elizabeth, later the Queen Mother, was Called as a Royal Bencher in 1944, in the still bombed-out Middle Temple Hall. She served as Treasurer in 1949, presiding with her husband the King (Treasurer of Inner Temple in that year) over a Joint Bench Dinner to celebrate the post-war restoration of Hall. The Queen Mother – who described herself as ‘First Daughter of Domus’ – was a familiar face at the Inn, regularly attending events such as Grand Day and the Family Dinner, as well as performances and ceremonies. Her last visit to the Inn was in December 2001, just a few months before her death.

More recently, Diana, Princess of Wales, was made a Royal Bencher in 1988, and her visits included a Special Mixed Dining Night in 1990, when she dined with student members of the Inn. The Duke of Cambridge was made a Royal Bencher in 2009, and the Smoking Room in the Bench Apartments was renamed the Prince’s Room in his honour. He and the Duchess of Cambridge have visited the Inn on several occasions since, including in 2017 when he met Duke & Duchess of Cambridge Scholars and introduced the Moot Final.

The Middle Temple’s long-standing royal associations have taken many forms over the centuries. This year we celebrate our warm relationship over many years with Her Majesty the Queen, as she marks her Platinum Jubilee.

Barnaby Bryan read Philosophy at King’s College, Cambridge, and later qualified as an Archivist at University College London. He has undertaken archival work at various institutions, including Unilever’s corporate archive in Port Sunlight. He joined the Middle Temple as a Project Archivist in 2015, progressing to Assistant Archivist in 2016 before being appointed as the Inn’s Archivist in 2019.