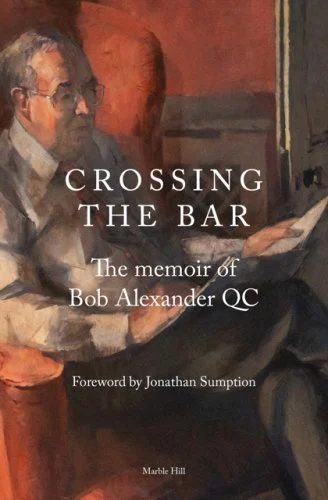

As a young Bar student whose one ‘lead’ for getting a pupillage had gone cold, I wrote to Master Bob Alexander. Within a short time, I was fixed up with someone in his chambers — someone who in the succeeding months taught me everything an aspiring barrister ought to know. 27 years later, when Bob was Treasurer of the Inn, I was the last new Bencher he Called. The chapter setting out his thoughts on the Iraq War of 2003 was left unfinished and is not included in this volume, but I had the privilege of hearing him set out his concerns about the legality of the war at a meeting of JUSTICE, one of the bodies he happened to chair. I thus approached this book not simply as someone who owed him debts of gratitude but who had been lucky enough to know him and to have witnessed the sense of humanity which infused his career.

One can see Bob’s name on the list of Treasurers: 2001. The summary of that year only takes up a few pages in the memoir, but it adds up to what he did to modernise the Inn, both in terms of our customs and of the fabric, and to make it a more open and educative place for students. His Grand Day may be remembered for its success in managing to entertain both Margaret Thatcher and John Major dining at the same [High] table. New Benchers are obliged to give a short talk once they are Called. Previously, this took place in the Parliament Chamber amongst the people who had elected them. It was Bob who moved this into Hall so that everyone could be introduced to them.

As one reads the memoir one steadily becomes aware of the breadth of Bob’s CV: Chairman of the Bar (when he founded Counsel magazine), Chairman of the Take Over Panel, Chairman of National Westminster Bank, President and Chairman of the Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC), Chairman of the Royal Shakespeare Company, Chairman of JUSTICE, Chancellor of Exeter University and an active life peer.

Barristers will want to read about Bob’s leading cases, but it is important to note as well the chapters about family and education. The latter was not in law but in English. He was an undergraduate at King’s College, Cambridge at a time when he was taught by legendary dons including CS Lewis, George (Dadie) Rylands and FR Leavis. In particular he saw a lot of EM Forster, although ‘for him conversations included silence’. Rejecting the careers to which an English degree might lead, he eventually chose the law, the Bar, and Middle Temple who granted him a scholarship of £300 a year for three years, ‘a priceless bridge to the profession’.

What every barrister reader will remember is how Bob described his own aptitude for the profession. ‘Success at the Bar called for a good, incisive mind and skilled and sensitive advocacy. I had not managed to get a first-class degree and I had not seen myself as a serious player in the top intellectual league. I had lacked the bottle, through a combination of diffidence and a feeling of intimidation from the talents around me, to speak in the Cambridge Union. I was sometimes diffident and still had slight asthma. But strangely I had always felt that I ought to be able to perform well in the structured environment of a courtroom.’ And so, it turned out to be.

What distinguishes the eight chapters about Bob’s cases is the measured way in which he describes them. He sets the scene, he brings in his own role and contribution, he explains why things turned out the way they did, and then he allows himself to pass comment on the merits. There is no bragging.

To give some examples:

He represented the government in the House of Lords in the appeal against the government’s decision to ban unions at GCHQ. It was the one case that year which took place in the House of Lords Chamber itself, with the advocates at the bar, with nowhere to put papers or books, while the Law Lords themselves sat on the benches a bit too far away to hear them easily. Bob includes the fact that the judge at first instance found against the government but that did nothing to prevent Mr Justice Glidewell being promoted to the Court of Appeal: Mrs Thatcher as a barrister had a scrupulous respect for the division between the executive and the judiciary… she never criticised judicial decisions publicly,’ a custom now abandoned by her successors. Bob won on the ‘narrow ground’ of national security, but it taught him of the need for consultation when people’s rights are affected. Two years later, as Chairman of the Bar, he successfully judicially reviewed the then Lord Chancellor who had failed properly to consult the Bar over criminal legal aid fees.

There is the ‘Fares Fair’ case brought against the then Greater London Council then led by Ken Livingstone. ‘Of all the cases I argued at the highest appellant level, this is the one in which to my mind, the reasoning of the court was most doubtful’. ‘To my mind, the function of public services enables wider socio-economic considerations to be taken into account’.

Bob did two cases in Singapore, one representing the Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew, who was suing a political opponent for libel, and years later, one representing a solicitor detained without trial on grounds of national security. After the first case, Bob was invited to a large dinner to entertain the legal team. Lee asked him whether he still dined with his opponent on Circuit, and when he was told that Bob did, he offered this advice, ’when you dine with an opponent, you should drink white wine and give him red wine. Red wine is bad for the voice, and you will have the advantage in court the following day’. After the second case, and despite having been on the ‘other side’ to the governing party, Bob was invited round regardless by the Prime Minister and the two men had an amiable conversation, while avoiding the facts of the case.

The most detailed chapters in the book deal with Bob’s career after the Bar, with the National Westminster Bank and later as Chairman of the Royal Shakespeare Company. Both act as lessons in the challenges of entering worlds which operate very differently from the Bar. ‘NatWest: Culture Shock’ is the apt title of the chapter which sets out the sudden offer and his decision to take on the job while the bank was in crisis. When he arrived for his first pre-board lunch, one director assured him, ‘I always like a couple of good glasses of Chateau Latour 1970 before a board meeting’. The problems became a good deal more complex. The chapter describing his life after leaving the bank is entitled ‘Freedom’.

Cricket was one of Bob’s passions, and his ten years of close involvement with the MCC during which time women were finally allowed to join, was a happy one. More mixed was his experience with the Royal Shakespeare Company (RSC). Shakespeare unsurprisingly had been ‘the deepest influence in my study of literature’. But as with banking, and unlike the Bar where cases come and go, the challenges the RSC rolled on. The artistic director, Adrian Noble, left; the company had decided to give up the London home which had been designed for it at the Barbican Theatre but without a viable alternative, and there was a difficult relationship with his vice chairman. Here, as with the bank, the personalities of the people he dealt with were more significant than those of his opponents in court, and he deals with this quite openly.

This is much more than a former barrister’s memoirs of life in court. Cambridge, the Bar, the Inn, the outside world—they are all there, described with brilliance and subtlety. The careful reader will also, by reading between the lines, learn about a man whom we lost far too soon.

Master David Wurtzel was Called to the Bar by Middle Temple in 1974 and was elected a Bencher in 2001. He practiced in common law chambers for 27 years, before concluding his career by delivering legal training. From 2009-15 he was consultant editor of Counsel magazine.