While the Great Plague of 1665-66 is the most well-known outbreak of yersinia pestis to have ravaged London since the Black Death in 1348, the disease was endemic in the city throughout the 16th and 17th Centuries, breaking out into epidemics every 20 years or so. Such outbreaks saw the Middle Temple authorities forced to take measures which resembled, in many ways, a modern-day lockdown; these periods saw events such as the Reader’s Feast being cancelled, the Inn vacated by its members and Benchers, a skeleton staff left behind to keep things running and even a dose of scepticism and resistance to the measures put in place. These early modern lockdowns were often followed by a discernible sense of determination to return to social and cultural normality.

The population of London in 1600 was around 200,000, and over the following century this more than doubled, as men and women relocated from the surrounding countryside for work and waves of migrants fleeing religious persecution in Europe arrived, increasing pressure on space. Houses became increasingly overcrowded, partitioned into tenements for multiple families and well-meaning attempts to combat plague by demolishing the houses of the dead and curtailing the construction of new buildings only served to exacerbate the problem.

The earliest recorded Middle Temple lockdown was in 1592, when the bubonic plague reached London in August, rapidly spreading through the city’s crowded suburban parishes. Activity at the Middle Temple swiftly shut down and a note in the minutes of the Inn’s Parliament records that, ‘no commons were kept in the House from the 7th day of August, 1592, to the 20th day of January following, by reason of the sickness’. The next two Readings were cancelled, and when the Inn’s Parliament did meet, it did so at St Alban’s. This meeting included two Calls to the Bar – which may give the occasion the honour of being the Inn’s first ‘remote’ Call ceremony.

The first decades of the 17th Century saw a long period of intermittent plague in London. The death of Queen Elizabeth I in March 1603 and the accession of James I to the throne coincided with a particularly deadly outbreak, disrupting James’ formal entry into the City of London. One of his first actions as monarch was to issue a Book of Orders, aimed at controlling the spread of disease through measures such as confinement of the sick, burning of infected property and monitoring of infections; financial support for those confined to their homes and unable to work was also to be provided. The book also included a range of recommended medical mitigations, which included the perfuming of clothes with juniper, eating sorrel sauce and – the centrepiece of early modern medicine – bloodletting.

On 8 July 1603, as the outbreak grew worse, the Inn’s Parliament ordered that, ‘All gentlemen of this House, clerks and serving men, shall depart and not be suffered until such time that it shall please God to cease the sickness’. As part of a general evacuation of the capital, the courts of law moved to Winchester and the Inn’s Parliament met there on 23 November. Earlier that month, the trial of Sir Walter Raleigh had taken place in the Great Hall of Winchester Castle; he had been sentenced to death by his fellow Middle Templar, Sir John Popham.

Rules and regulations imposed to mitigate the spread of infection, much as today, were not always met with universal cooperation: one occasion illuminates well this early modern lockdown-scepticism. In the summer of 1630, the Inn had been evacuated due to rising levels of infection and when Parliament convened in November, the Benchers ordered that no commons would be held over Christmas, ‘in consequence of the danger of infection from the resort of all people to the House, in respect of play there, contrary to the ancient course’. Commons were broken up until 15 January, with certain officers appointed to guard the Inn.

The minutes of Parliament from the following January record that, ‘Divers young gentlemen of the House then in commons opposed the order for breaking up commons, on pretence of their liberties (as they termed it) being infringed, whereas no liberty in the House may exempt them at any time from being governed by the orders of the Masters of the Bench’. It emerged that these young men had, having broken into Hall, set up their own Parliament and put the Inn’s Steward in the stocks for refusing to serve them commons. After the ringleaders were fined, they marched into Hall, hurling both abuse and pots at the Benchers at High Table during dinner.

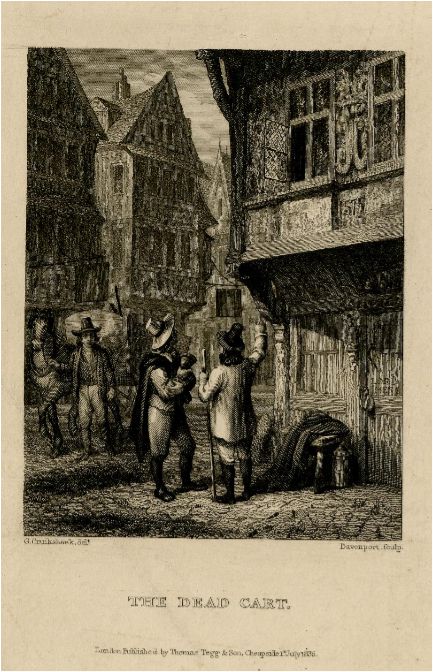

By the mid-1660s, the overcrowding, congested streets and filthy conditions in London had reached critical levels, leaving it acutely vulnerable when the Great Plague arrived from the continent, possibly on Dutch trading vessels. In the face of rising death rates in the suburbs and dockland areas in the Spring of 1665, the government introduced preventative measures and household quarantine – from the Italian quarantina, meaning ‘forty days’ – which condemned households containing plague victims to be boarded up for that period, a red cross painted on their door.

The Inn reacted quickly, and on Tuesday 13 June 1665, Parliament cancelled the Summer Reading and dissolved commons. They ordered that the gates and passages ‘between the Houses’ be made up – essentially sealing the Middle Temple off from the Inner Temple. The Benchers evidently joined much of the London elite in fleeing London, the minutes recording that ‘their Masterships take it kindly that the Under Treasurer has offered to stay in town in this dangerous time, and have therefore left all things to his care’.

The Inn’s Parliament did not meet again until the following February, when the royal court returned to London. The Benchers awarded the stalwart Under Treasurer, James Buck, a chamber as a reward for his service to the Inn throughout the time of the plague, as well as £10 to the Porter. Evidently not all members had been able to escape London – at least one unfortunate Middle Templar, Thomas Goodhand, had contracted the plague and died in his chambers in the intervening months, his ‘infected goods’ being removed and quarantined. While the plague subsided somewhat in the spring of 1666, infections continued to spike, the Summer Reading once again being cancelled and commons broken up throughout July and August.

One can discern, in the records from the weeks and months immediately after these periods of epidemic and disruption, a sense of determined return to normality. Educational, social and cultural activities were reinstated as soon as was considered safe, and sometimes with renewed energy. After an outbreak in the mid-1630s, at the All Hallows’ Feast, a play was performed in the Inn by Queen Henrietta’s Men. This was one of the premier companies of the period, itself having been formed following the plague of 1625. The company had broken up during the most recent epidemic, but was reconstituted in October 1637, based at Salisbury Court. The name of the play was not recorded, but may well have been The English Moor, or the Mock Marriage. The Great Plague, which had subsided by autumn 1666, was followed by a particularly sumptuous Grand Day feast for All Hallows. The Inn’s financial records indicate a greater sum than usual being laid out on food and wine for feasting; on staffs, wands and truncheons for revelry; and for music performed in Hall by John Beardwell, a London musician and member of the Musicians’ Company. After such a traumatic period of dislocation, uncertainty and danger – no doubt compounded by the Great Fire of London less than two months earlier, and the ongoing Second Anglo-Dutch War – one can only imagine the sense of relief.

Barnaby Bryan read Philosophy at King’s College, Cambridge, and later qualified as an Archivist at University College London. He has undertaken archival work at various institutions, including Unilever’s corporate archive in Port Sunlight. He joined the Middle Temple as a Project Archivist in 2015, progressing to Assistant Archivist in 2016 before being appointed as the Inn’s Archivist in 2019.