with promptings by William Shakespeare.

Excerpt of a talk given to the Historical Society in December 2019.

Master Igor Judge was Called to the Bar in 1963. He was made a Bencher in 1987. He was President of the Queen’s Bench Division and then Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales 2008-13. In 2013 he became a Distinguished Fellow and Visiting Professor at the Dickson Poon School of Law at King’s College London. Between 2015 and 2017 he was Chief Surveillance Commissioner. Since 2017 he has been Commissary of Cambridge University. From 2007-2013 he was President of the Selden Society. He was Treasurer in 2014.

I really cannot quite remember when I became interested in collecting documents. To begin with, however, we could not afford to buy them. I remember the seal of Ranulph de Blundeville, Earl of Chester, who graciously made way for William Marshal to be elected as Regent for the boy king, Henry II, when King John died; another that got away was a letter from one merchant to another on his way to the Council of Constance in 1415 setting out the details of a great victory by King Henry V at a village called Agincourt. The fatality details given by him pretty well coincided with Shakespeare and would not have supported President Macron’s recently expressed analysis of that battle. At that time, however, Judith, my wife, thought that our children needed carpets and curtains in their bedrooms rather more than they needed ancient documents.

Here we are today standing on land owned and occupied by the Knights Templar, the greatest crusading knights and probably the richest organisation in mediaeval Europe, other perhaps than the Church. Almost exactly 100 years after Magna Carta, in 1312, the Knights Templar were suppressed. Twenty, or even ten years earlier, the possibility that this great Order might disappear would have been laughable. But it did, for political reasons, on trumped charges. Nothing is ever certain; ‘what’s to come is still unsure’ is not merely one of Shakespeare’s greatest lines, but in giving those lines to the Court Jester or Fool, he is surely laughing at the human condition.

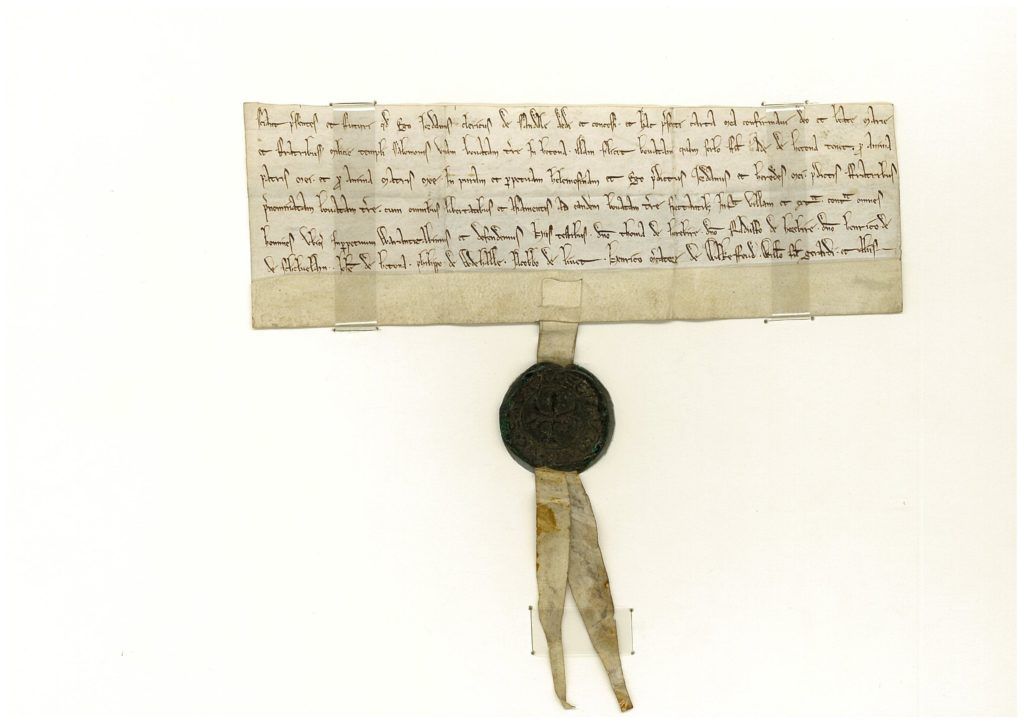

The land was then given to the Knights Hospitaller, the Order of St John, and the lawyers moved in, and quickly. They were certainly here by 1340 or thereabouts and they have never left. The Inns were invaded and all records then available were destroyed in 1381 in Wat Tyler’s rebellion. They were re-invaded by Jack Cade in 1450, when again, all our records were destroyed, thus giving Shakespeare, in all the blood and horrors of the three parts of Henry VI and Richard II, his only joke, ‘the first thing we do, let’s kill all the lawyers’. Laughing at the joke, audiences forget the wild destruction and the murders of the residents. One result is that at Middle Temple we have no domestic or administrative documents from before 1501. So I could not resist the earliest document in this collection, a donation to the Knights, no doubt for the benefit of his immortal soul, by a clerk in Yorkshire of a bovate of land, that is, as much as an ox could plough in a day. It provides a direct link between those far off, pre-lawyer, days at the Temple, and demonstrates how that Order was still flourishing just a few years before, when out of the blue, it was destroyed. I found that document in a very uninteresting job lot, and it was sold to me at a nominal price. Some years after I presented it to the Inn, the bestseller, The Da Vinci Code was written, and I understand that our insurers said that as anything to do with the Knights Templar had become fashionable and valuable, the original must be kept in the Archive, and that only a facsimile should be put on display. There it is, in the Prince’s Room.

This document, like all of them, reminds me, and us, that with any document we are in touch with the human beings who wrote them, or are described in them, and handled them, and their lives, and that we should pause to reflect on how and in what circumstances they were created and how delivered, by what means of transport, or retained, and where, and who read them, and acted on them, and were affected by them, and over the centuries kept them. When you hold an ancient document, when you are looking at it, you are living with history. Indeed documents do not have to be very ancient. The letters our parents wrote to each other when they were separated by war, even totally personal letters, would tell us their history. With documents you are always close to human beings, sometimes historical figures, but always human beings, each one a different character.

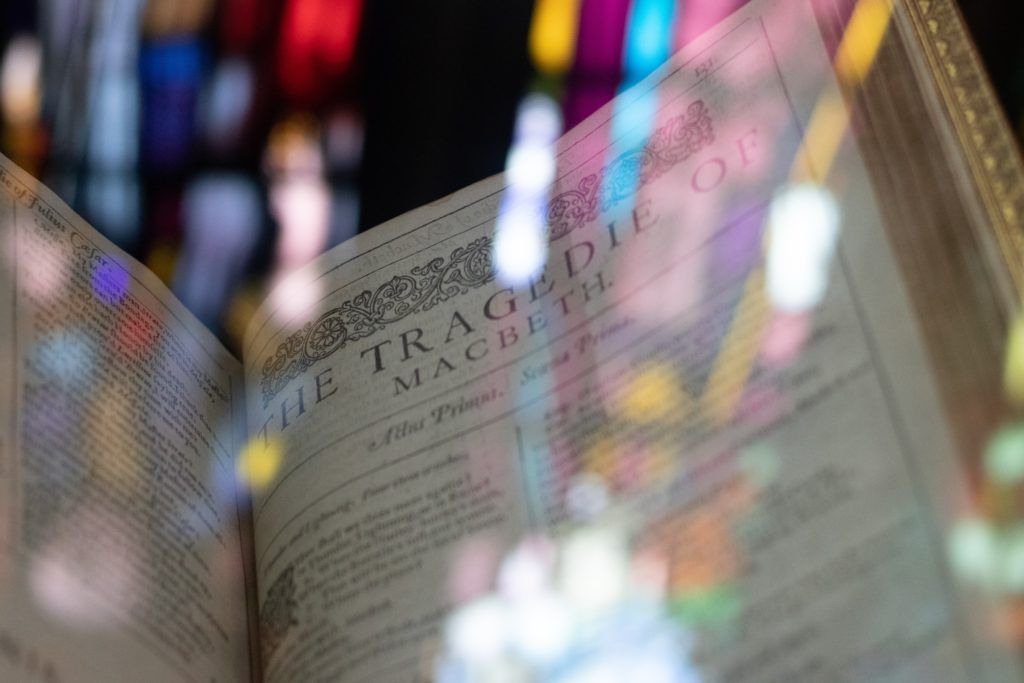

When I started collecting I realised I would have to be specific in my choice because, literally, every century could be covered, and I could not afford either the time or the money for that. So I settled for the 15th Century. When I was at school, and then at University, this century was regarded as, somehow, not very serious history. But I was attracted by the century because I loved and still love Shakespeare, and although his history plays are certainly not his greatest plays, they cover the 15th century in England in unbroken continuity until 1485. Beyond the battle of Agincourt, and one King ruling England and France, the loss of France, the Wars of the Roses, as we now call them, the endless battles at Northampton and St Albans, the Kings themselves, depressed, usurping Henry IV, martial and triumphant Henry V, feeble, saintly Henry VI, sexually incontinent Edward IV, the child victim, Edward V, murderous Richard III, secretive, suspicious but successful Henry VII, there was much and there remains much of interest. But in those days we rushed through until, hurray, here are the Tudors and Stuarts.

Plantagenet England was much more sophisticated then we imagine. Parliament was invited to decide succession to the Crown in 1450, and both Richard III and Henry VII sought Parliamentary confirmation of their right to it. The Paston Letters reveal a society in which, contrary to common belief, the woman played distinctive, positive parts, through the generations, offering valuable advice to their husbands, who followed it and treasured them. It is the century of the printing press, which among many other things, enabled us to ask questions about God and religion, the conscience and ultimately the freedom of the individual. And if you doubt the relevance of the plays themselves, read the very recently published, weighty, albeit short, book by Stephen Greenblatt, Tyrant: Shakespeare on Power. It suggests that the question which the plays seek to answer is simple: ‘how is it possible for a whole country to fall into the hands of a tyrant?’. That is a question which cannot be ignored in any century, least of all our own; think Hitler, Stalin, Franco, the chilling roll call in Europe alone. It is not even a question for history. The process still continues to this day.

I never did find another document about the battle of Agincourt itself, but the collection does include an order by the Duke of Orleans. Remember his impatience, the certainty of victory on the night before the battle. ‘Will it never be morning’: and then ‘it is now 2 o’clock. Let me see by ten we shall each have 100 English men’: and then, ‘the sun doth gild my armour, Up my Lords’. After the battle he was found, just alive, beneath a pile of corpses, and from there taken to London where he remained a prisoner of war for 25 long years. This letter confirms that he is indeed a prisoner, trying to sort out his affairs at home. He never gave up plotting and planning for his release, but he also founded his own library and wrote a large number of lyric poems, and they show us that although in 1415 the French were not very good at battles, they were well ahead of us as writers of sonnets. It was 100 years or so later before Henry Howard, in forlorn and unrequited love, was able to take solace with the last lines of a powerful sonnet: ‘Hers will I be, but only with this thought,/ Content myself though my hopes be nought’. The English side of the battle is represented by Sir John Fastolf, with the Great Seal of Henry IV attached. Incidentally Henry IV, Henry V, and Henry VI had identical seals, perhaps to create a sense of continuity for a rather vulnerable dynasty. Fastolf served in the campaigns of Henry V at Harfleur, where no doubt he heard and was inspired by ‘Once more unto the breach, dear friends, once more..’, and he was there at Agincourt itself. In truth he was a brave and, perhaps important to emphasise, sober soldier. But this document reminds us that nothing changes. Someone had to be blamed for the significant English defeat in France at the Battle of Patay in 1429. Scapegoats are not a modern creation and he, poor chap, took the blame. So Shakespeare has him saying ‘…Away./ To save myself by flight/ We are like to have the overthrow’. So he ran away and a few scenes later we see the Garter torn from his leg and the King’s insulting description of him as a ‘stain to thy country’.

The document reminds us of another constant facet of human life. Be careful who you tangle with. When Shakespeare first wrote the Henry IV plays, the name given to the dissolute, disreputable friend of Prince Hal was Oldcastle. No harm in that, he was a Lollard, a heretic, and a traitor. He suffered a most terrible death, burnt alive in a deliberately prolonged burning. So this was not a bad name to choose, except that Shakespeare overlooked that, at the very time he was writing, the company he wrote for and acted in was the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, and that the Lord Chamberlain, Lord Cobham, was a descendant of Oldcastle. Imagine the panic when it was realised what a dangerous howler Shakespeare had perpetrated. ‘For God’s sake, Will!’ who immediately appreciated that the name he was looking for was certainly not Oldcastle, but Falstaff. What a wise choice.

The steady decline of English fortunes in France is represented by documents in the name of John, Duke of Belford, as ‘Regent of the Kingdom of France’, written in French, who was hardly a modern man when he rather dismissed Joan of Arc as ‘… A maid, and be so martial?’, And Richard, Duke of York, who succeeded him as Regent. Richard of course, represents the Yorkist side of the Roses. The Temple itself is the dramatic, tense setting for the selection of roses, white for York and red for Lancaster. ‘From off this white briar pluck a white rose with me’, says York.

Spare a moment of sympathy for the unknown lawyer who happens to be around the Temple Gardens and is asked to give his opinion as this great row unfolds and who speaks against the red rose, but with this important legal precondition: ‘Unless my study and my books be false/ The argument you held was wrong in law’. Remarkable, isn’t it? How those last three words would have been spoken in courts up and down the land for centuries, probably every day this week, and every day this year. The government’s argument before the Supreme Court on prorogation was indeed held to be ‘wrong in law’.

This very modest and circumspect legal advice gave Warwick the excuse he wanted for supporting York. He foresees the consequences of this seemingly trivial moment. ‘And here I prophesy this brawl today/ Grown to this faction in the Temple Garden/ Shall send, between the red rose and the white,/ One thousand souls to death and deadly night’.

The documents include two protagonists on the opposite sides. One is a document with the personal signature of William Oldhall, a loyal Yorkist, probably present at Agincourt, certainly a veteran of the battles in France, and in 1450 the Speaker of the House of Commons when it was decided that York should succeed Henry VI. An interesting example of the 15th Century perception of the importance of Parliament. On the other side, a signed document by Robert Molyns, Lord Hungerford, and similarly loyal Lancastrian, finally executed after the Battle of Hexham in 1464. His real claim to fame, and I would add notoriety, features in the Paston Letters with his troops attacking the Paston home eventually being fought off by Mrs Paston, Agnes, I think she was. She wrote to her husband in London, in very modest terms, telling her husband of what must have been a bruising, indeed profoundly alarming encounter with armed men. In these letters the reality of the Civil War is very alive.

And the documents illustrate the ebb and flow of the tides of war.

Edward IV confirms the governorship of Calais on the Earl of Warwick the Kingmaker, and does a good little rewrite of history, by ensuring that it refers to ‘Henry VI in dede and not of right King of England’. Public relations mattered even then. And this is followed up by the betrayal by George, Duke of Clarence, of his brother Edward IV. The document in his name, with his seal, just a few years later in December 1470, is dated the ‘49th year of Henry VI’. You all know about ‘false, fleeting, perjured Clarence’, and his drowning in a barrel of malmsey. There is a legal subtext to this document, as the beneficiary was Mr Justice Littleton, the author of Littleton on Tenures, the first legal textbook to be printed and published in England, much praised by Sir Edward Coke, no doubt a little biased as he produced a new edition.

Chronologically this document is followed up soon afterwards by a document with the personal signature of Louis XI of France, instructing his Chancellor that the affairs of Queen Margaret were important to him, and that her pension must be paid. It should have been a scene in Shakespeare.

Shakespeare has Warwick going to France to persuade Louis XI that his sister should marry Edward IV. When he enters the court, Queen Margaret, ‘She Wolf of France’, a description perhaps unsurprisingly given to her by York before his death, greets him ‘And see where comes the breeder of my sorrow’. Warwick is doing very well with his mission until they get letters telling them of Edward’s marriage to Elizabeth Gray. Warwick now rails against Edward ‘For matching more for wanton lust than honour/ Than for the strength and safety of our country’ and so on, until ‘To repair my honour, lost for him/ I here renounce him and return to Henry’. Louis XI, the spider King, on whom some say Machiavelli based The Prince, naturally changes side too.

And so they sailed back to England, to the disasters at Barnet where Warwick was killed with Shakespeare giving him powerful dying words, ‘For who lived King, but I could dig his grave?/ And who durst smile when Warwick bent his brow’ and then on to Tewkesbury shortly afterwards where the boy Prince of Wales was killed.

Balancing the death of the Lancastrian heir to the throne, we have the murder of Edward’s sons, the Princes in the Tower. The document is a contract between James Tyrrell and Richard Wase, buying and selling the proceeds of any judgement in civil proceedings. The deal is that if Wase is successful in proceedings brought with the financial support of Tyrrell, Tyrell will be paid half the proceeds. In other words, champerty, made a crime by Henry VII, which was, I believe, still a crime and would certainly have been unenforceable when I started at the Bar. Nowadays, of course, we have conditional fee agreements.

Tyrrell you will remember was ‘A discounted gentleman whose humble means match not his haughty spirit’, who reported to Richard III that ‘The tyrannous and bloodied act is done – the most arch deed of piteous massacre/ Ever yet this land was guilty of’. Then he recounted how one of the murderers told him… ‘We smothered/ The most replenished sweet work of Nature/ That from the prime creation e’er she framed’. These lines can still move a modern audience to damp eyes.

I had to have a connection with Henry VII, the cynic who backdated the beginning of his reign to the day before Bosworth, so that all those who fought for Richard III, their anointed king, were guilty of treason, and there is one from the 15th Century. My real opportunity came three years outside my self-imposed century. This is a contemporary document from January 1503 giving the text of marriage vows exchanged between James IV of Scotland, represented by the Earl of Bothwell, and Margaret Tudor, then a child.

This led ultimately, of course, to the Stuart dynasty, James succeeding Elizabeth, and in 1608 conveying the lands which had been in the ownership of the Knights Hospitaller until their own dissolution in 1540, to the Middle and Inner Temple. And so, here we lawyers still are.

Beyond Shakespeare I was interested in documents with a legal connection. The Roll of the Abbess of Burnham tells the story of daily life between 1416 and 1418 when kings and nobles were battling over France. My favourite entry shows how in 1416 Harry was in mercy for having watered ale, but two years later he becomes the foreman of the jury adjudicating on whether someone else had watered the ale. Although it is completely irrelevant, I recently discovered that Shakespeare’s father, John, was for a time responsible for checking the quality of the ale in Stratford. Another document is a manumission granted by the Abbess of Shaftesbury in 1439, manumitting William Carter from villein status. Until I saw this document I had not appreciated that this lowly status formally continued until the middle of the 15th Century. A third document, or four documents together reflect a contract for the sale of land in Northamptonshire in 1443. What is unusual is that we have the vendor’s copy and the purchaser’s copy of identical provisions, with the cuts between each side which show that the documents fit perfectly together, thus proving that they are indeed the same contract, together with letters of attorney and conformation from both sides to the contract. So, long before there were proper roads, and certainly before telephone, they brought together individuals from as far apart as what is now Moss Side, Manchester, Leicester and Northamptonshire. We tend to be rather arrogant, well, certainly patronising, about our ancestors, unconsciously linking their lack of what we regard as modern facilities with some sort of incapacity. Yet human capacity does not change very much. We simply learn to use new tools, and so my most recent acquisition is a document from a legal textbook of Civil Law, in Latin, which I have not tried to translate or have translated. To me personally the significance of a printed document from before the end of this collection of 15th Century documents is that this one symbolises the vast societal and intellectual change consequent on the invention of printing.

And one final self-indulgence. Naughtily outside this particular century, a bond signed in 1536 by the then Lord Mayor of London, and John Fitz James, at that very time Chief Justice of the King’s Bench Division, who had earlier been the Treasurer of the Inn. Nowadays we deplore his subservience to Henry VIII, giving insufficient understanding of the times in which he lived. The report of a courageous observation at the trial of Thomas More, ‘if the Act of Parliament be lawful, then the Indictment is not insufficient’, raised a constitutional issue about the extent of Parliamentary sovereignty which has not yet quite gone away. And I do rather like this observation attributed to him in a 1523 manuscript (not, alas, in my collection) ‘two main principles guide human nature, conscience and law; by the former we are obliged in reference to another world, by the latter in relation to this’. That, too, might be the subject for discussion on another day.