Address given by The Reverend Mark Hatcher,

Reader of the Temple

November is the month of memory, of remembrance. Beginning with All Saints’ Day, followed by All Souls’ Day and now Remembrance Sunday. We come together to stand with those who, down the generations, have been told of the death of a loved one. We remember those who today, and in years long past, have made the ultimate sacrifice, not least in the two great wars of the last century. They gave their lives for liberty, that we might enjoy the fruits of peace, justice and stability.

More than 880,000 British soldiers – 6% of the male population – were killed in the Great War of 1914-1918 and almost 2 million wounded returned home to find that little provision had been made for them. In 1921, Earl Haig founded the British Legion to support returning veterans and their families and Britain’s first Poppy Day (as it was known) was organised for Friday 11 November of that year. It was a huge success. Nine million poppies produced sold out. Poppy Day became an annual event, as did a remembrance ceremony at the Cenotaph and the two minute silence in Whitehall.

However, in the 1960s and 1970s as memories of wartime began to fade and survivors died. It seemed as if poppy fatigue would set in, and ceremonies of remembrance might wither. Yet when, after the Falklands conflict, Britain went to war again – first in Afghanistan in 2001 and then in Iraq in 2003 – the poppy gained a new lease of life. Over the last 20 years or so, this symbol of remembrance has become increasingly ubiquitous and with it, the solemnity of remembering, with gratitude those who have died in action has often been at odds with the proliferation of poppy-related merchandise and the satisfaction of emotional self-indulgence.

It is not our emotional needs but gratitude to those who sacrificed themselves which should lie at the heart of this weekend’s sad observances. It is by remembering and retelling a story, which is part of any culture and not always easy, whereby the horror of war and the tensions in war between inhumanity and humanity are revealed.

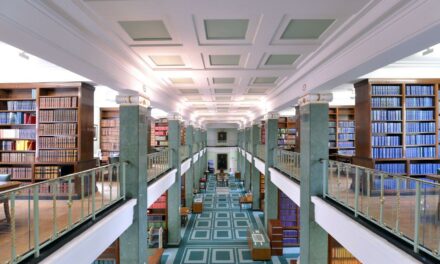

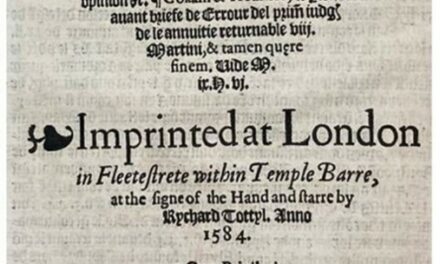

It is hard to imagine that this beautiful and ancient Church, consecrated over 800 years ago where the terms of Magna Carta had been negotiated, was desecrated during the Blitz on the night of Saturday 10 and Sunday 11 May 1941. High explosive and incendiary bombs rained down on the City of London, Westminster and the Temple, melting the lead on the roof of the Church and reducing the fabric and contents to rubble. It was the fate of so many of the buildings in the Temple that night including the Master of the Temple’s House, built by Wren in 1667 and with it the heirlooms of the House: Richard Hooker’s table and chair, portraits of former Masters and so many books.

The buildings of the Temple were decimated, buildings rich in their associations with the great men who had wrought and fought for liberty, who laid the foundations of our law and produced works of great literature. It was in Brick Court in Middle Temple, for example, where Oliver Goldsmith lived and entertained Dr Johnson. It was here that Blackstone wrote his commentaries and Thackeray had his chambers. They were all destroyed. The beautiful staircases up which generations of solicitors, attorneys and clients would have climbed for conferences and consultations were burnt to a cinder.

That night the air had been filled with the awful whining of falling bombs like rushing express trains. The following morning a thick fog of brick dust hung like a pall over everything to join the smouldering ruins for days after. True it was reported that sundials were easier to read, because so many buildings were down but this was small consolation with the wreckage that had been left. At the beginning of the War in 1939 there were 285 sets of chambers; by the end 112 were completely destroyed.

Today we recall in particular the members of the Inner and Middle Temple, whose names are inscribed in the Round and appear in the Order of Service. We also recall members of the Temple Church choir who were killed and whose names are listed in the Choir Vestry, and we recall the names of members of the Inns of Court Mission who are listed in the Triforium.

It may seem invidious to mention individuals in this context when there are so many in the Temple community, men and women, who gave their lives in the two wars. But even this tiny retelling, these vignettes, is part of our remembering.

Members of the Temple were some of the first to fall in battle in 1914. For example, Lieutenant James Gilkison, a member of the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, was Called to the Bar by Inner Temple in 1906. He was one of the first to be sent out to France and was killed on Wednesday 26 August 1914 at the Battle of Le Cateau. His brother was killed barely a month later.

Raymond Asquith, the eldest son of the Prime Minister, was Called to the Bar by Inner Temple in 1904. He had achieved a glittering career at Oxford and become a fellow of All Souls. He began to build a prominent practice at the Bar. He joined the Grenadier Guards at the outbreak of the war. His unit was present at the Battle of the Somme which began on Saturday 1 July 1916. 20,000 British soldiers died on the first day, and a further 37,000 were injured. It was the heaviest ever loss for the British Army on a single day of battle. Raymond Asquith was shot through the chest on Friday 15 September. He lit a cigarette after he fell to conceal from his men the seriousness of his injury. He died before reaching a forward dressing station. His friend Winston Churchill wrote: ‘…These gallant charming figures that flash and gleam amid the carnage – always so superior to it, disdainful of death and suffering – are an inspiration and example to all. And he was one of the very best.’

It was not just the barristers and students of the Inns who contributed to the war effort but also the Inns’ staff. Charles Hunt, for example, joined the staff of Middle Temple in 1908 as a plateman and wine waiter in Hall. He was extremely well thought of at the Inn and was being groomed to succeed the Inn’s Butler on the latter’s retirement. He joined the reserves in 1915 and was called up a year later. He was killed by a stray sniper bullet on Wednesday 4 September 1918. The Inn’s Archives contain voluminous correspondence about his career in the Army, his death and the Inn’s later support for the education of his two sons.

We remember the dead. We remember young lives cut short and we remember some very young lives cut short.

15 members of the ‘Templars Union’, an association of serving and former members of the Choir and choristers, which had been established by Dr Walford Davies, were killed during the First World War. A memorial book, published by the Temple Church in 1923, contains biographies of these young men, like Harry Dixon (known as ‘Squib’), the fourth of six brothers, in the choir who was killed in action on Sunday 2 May 1915 at the battle of Ypres. ‘Waddy’ Waddams was another choirman. He seized a live grenade, saving a colleague, but he was so severely wounded by its explosion that he died the following day. What shines through the sepia photographs of these young men and their biographies is their selfless character, their courage, helpfulness and their sense of humour. One of them was awarded the DSO, a month before his death, aged 20. Another was awarded the Military Cross for having, single-handedly, captured an enemy machine gun and taken two prisoners.

We remember today and retell the stories of those who have fought, as a mark of respect, and to give profound thanks for their selfless sacrifice, because by retelling their stories we can hope for a more peaceful future. So let us remember the sacrifice that has been made. Let us remember both the courage and determination but let us also recall and lament the terrible evils of war. Let us not shy away from struggling with the dilemmas that war brings. And let us not stop asking questions of God – for this we must do if we hope for a world of peace.

We come together this Remembrance Sunday as we recall God’s purpose for us, revealed in the person of Jesus Christ, who came as the Prince of Peace. It is in the person of Jesus Christ that God’s purpose is revealed to us. That is a purpose above all that we should live as one which is not to rule out the possibility of discord or even war.

The distinctiveness of a Christian response might be known in the risk which is taken by seeking peace against the odds. The intentional, peaceful search for peace enables the peacemaker to be reflective of the very nature of God, which is both distinctive and transformative. Distinctive because Christian discipleship constantly seeks to proclaim the good news of Jesus Christ; transformative because that is the hallmark of the kingdom of heaven: everything is changed.

On All Saints’ Day 1922 there was a service of dedication here of the War Memorials of the Inner and Middle Temple. Cosmo Gordon Lang, then Archbishop of York (who incidentally began his career as a barrister of Inner Temple),gave the Address at the Service of Dedication. He said it was fitting that a memorial of the members of these two honourable societies who died in war should be placed here in the Temple Church. For centuries, through all the changes in the life of the nation, this Church had borne its unchanging witness to the things unseen and eternal, as it continues to do today.

‘It is fitting’ the Archbishop said, ‘that the names of these young knights of the Bar should be inscribed beside the figures of the old knights of the Temple.’ Today we add to the memories, recollections and traditions of which this Church is full, the memories of those brave men and women who gave their lives in two World Wars for freedom and justice, for you and me.

Every one of us, I think, has sufficient reason why, at the going down of the sun, and in the morning, we should remember them.

*****

(I am very grateful to the Archivists of the Inner and Middle Temple, Celia Pilkington and Barnaby Bryan respectively for their help with identifying various sources on which this Address was based. The Inns’ Archives help to keep alive the recollections of those who fell during the two Great Wars we remember today.)

Master Mark Hatcher is The Reader of the Temple at the Temple Church.