On Friday 1 May 1998, the United Kingdom construction industry had a dispute resolution process imposed upon them by Parliament, it was adjudication. Parliament had passed the Housing Grants, Construction and Regeneration Act in 1996 (ACT) but due to government and ministerial inaction The Scheme for Construction Contracts (England and Wales) Regulations took until Friday 6 March 1998 to be approved and was vital to support this new form of dispute resolution. Adjudication was a procedure designed to enable parties to resolve disputes relatively quickly and inexpensively. Under the Housing Grants, Construction and Regeneration Act 1996 (HGCRA 1996), parties to construction contracts have the right to commence adjudication at any time. In adjudication, parties refer their dispute to the adjudicator, who is an impartial decision maker. They will consider arguments from both parties and may also apply their own initiative and experience to the issues, before making a decision on how the dispute should be resolved. The adjudicator’s decision is legally binding, meaning that either party could obtain a judgment from a court, ordering the other party to comply with it and provisional, not final. This means the decision is binding unless and until the parties resolve the dispute in arbitration, litigation, or by agreement.

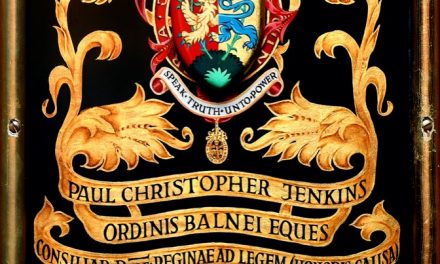

Many commentators commented that the ACT was poorly drafted and the first case that the court had to decide under the new Act was the case of Macob Civil Engineering Ltd v Morrison Construction Ltd [1999] CLC 739, BLR 93, 64 Con LR 1, 37 EG 173. The judge in the case was Master John Dyson, who was sitting as a judge in the Technology and Construction Court (TCC). The jurisprudence from this case alone has been significant and both ratio and obiter comments have been cited many times since it was heard. Master Stephen Furst was counsel for the unsuccessful defendant, whilst Master Michael Bowsher was counsel for the claimant.

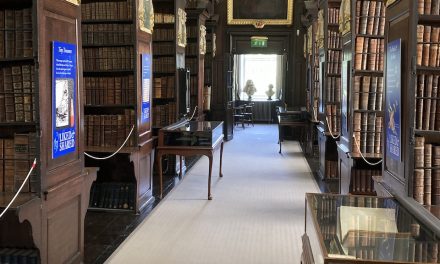

More importantly for adjudication, Master Dyson had been made judge in charge of the Official Referees court sometime before and had begun the process of modernising the court, which led to it being renamed the Technology and Construction Court on Friday 9 October 1998. The TCC and its judges would soon grasp what adjudication was, what did Parliament mean when it passed the Act and Scheme and how natural justice and insolvency defences would be decided in enforcement. The introduction in 1998 of the right to refer disputes in construction contracts to adjudication changed the landscape of litigation in the TCC. Lengthy trials of contractual disputes became a thing of the past, and the TCC faced the new challenge of devising speedy and appropriate procedures for enforcing adjudicator’s decisions when they are challenged. The TCC soon had a regular flow of enforcement cases from the ACT and created a swift process for summary enforcement of adjudicators awards.

Following Master Dyson moving on from the TCC, another Middle Temple Bencher became the judge in charge, Master Rupert Jackson. Just as Master Dyson, Master Jackson continued the courts support for adjudication by giving swift enforcement of decisions reached by adjudicators.

Throughout the evolution of adjudication, Middle Templars have played their part as counsel, advocates, adjudicators, expert witnesses and party representatives during the adjudication themselves, and then as counsel or judge during enforcement hearings. Some of the work has been undertaken by those holding practising certificates, some has not as adjudication does not fall into the regulated legal sector. Some of the cases have made it to the Court of Appeal and even the Supreme Court.

Notable cases in the Court of appeal have included:

- Abbey Healthcare (Mill Hill) Limited v Simply Construct (UK) LLP [2022] EWCA Civ 823

- John Doyle Construction Limited (in Liquidation) v Erith Contractors Ltd [2021] EWCA Civ 1452

- PBS Energo AS v Bester Generacion UK Ltd [2020] EWCA Civ 404

- Bennett (Construction) Ltd v CMC MBS Ltd [2019] EWCA Civ 1515, [2019] BLR 587, [2019] 4 WLR 155

- Gosvenor London Ltd v Aygun Aluminium UK Ltd [2018] EWCA Civ 2695

- Balfour Beatty Regional Construction Ltd v Grove Developments Ltd [2016) EWCA Civ 168

- PC Harrington Contractors Ltd v Systech international Ltd [2012) EWCA 1371, [2013] BLR 1

- Carillion Construction Ltd v Devonport Royal Dockyard Ltd [2005) EWCA Civ 1358, [2006) BLR 15

- RJT Consulting Engineers Ltd v OM Engineering (N.I.) Ltd [2002) EWCA Civ 270, [2002) 1 WLR 2344. 2346

Cases heard in the House of Lords and Supreme Court include:

- Bresco Electrical Services Ltd (In Liquidation) (Appellant/Cross-Respondent) v Michael J Lonsdale (Electrical) Ltd (Respondent/Cross Appellant) [2020] UKSC 25

- Aspect Contracts (Asbestos) Limited (Respondent) v Higgins Construction Plc (Appellant) [2015] UKSC 38

- Melville Dundas Ltd (in receivership) v George Wimpey UK Ltd [2007] UKHL 18, [2007] BLR 257

Various reports and studies into adjudication indicate that there are between 2,000 and 3,000 adjudications per year. Around 2,000 of the adjudications use an adjudicator that has been nominated by an Adjudicator Nominating Body (ANB). There are around twenty ANBs in the United Kingdom, though many of these make very few nominations each year. The King’s College report on Adjudication in 2022 confirmed that some of the more significant ANBs number had made 2171 nominations in the 12 month period from May 2020 to April 2021. The TCC report for 2021 to 2022 confirms that there were Adjudication decision enforcement hearings numbering only 148 in the period.

Very quickly arbitration and litigation in the domestic context fell due to the fact that parties were accepting the outcome of the adjudications and not taking matters on to litigation or arbitration.

Statutory Adjudication has evolved, and its current format is that is most likely that an adjudicator will be nominated by an ANB, the adjudicator will give a decision in 28-42 days, the parties will comply with the decision in over 90% of all matters, the court will usually enforce an adjudicator’s decision on a swift summary basis. The few areas that may cause the court not to enforce are a breach of natural justice or party insolvency, indeed an adjudicator can be wrong on the facts and law and still have their decision enforced.

Coulson LJ said in the case of John Doyle Construction Ltd (In Liquidation) v Erith Contractors Ltd [2021] EWCA Civ 1452, [2021] Bus LR 1837, [2021] WLR(D) 516):

I rather cavil at the suggestion that construction adjudication is somehow ”just a part of ADR”. In my view, that damns it with faint praise. In reality, it is the only system of compulsory dispute resolution of which I am aware which requires a decision by a specialist professional within 28 days, backed up by a specialist court enforcement scheme which (subject to jurisdiction and natural justice issues only) provides a judgment within weeks thereafter. It is not an alternative to anything; for most construction disputes, it is the only game in town.

The Technology and Construction Court celebrates its 150th Anniversary this year and it is without doubt due to the support and swift enforcement process for adjudication created by the TCC judges, that adjudication has grown and thrived for the last 25 years. The contribution of Middle Temple members has been significant to this form of dispute resolution.

Sean was Called to the Bar in 2017. His primary profession is Chartered Quantity Surveyor, and he regularly has acted as a quantum expert across the globe on construction, engineering and shipbuilding disputes. He is on the FIDC President’s List of adjudicators and mediators and sits as mediator, adjudicator, dispute board member, arbitrator and expert determiner. Sean has served on the Council of the Society of Construction Law since 2020.