Victoria joined the Inn as Projects Archivist in 2017 and was promoted to the position of Assistant Archivist in 2019. For over three years she was the Archives Assistant at the V&A Museum’s Archive of Art and Design, and during this time achieved a Postgraduate Diploma in Archive Administration.

The influenza pandemic of 1918/19, known as the ‘Spanish Flu’, killed 50 million people worldwide, and 228,000 people in Britain alone. The virus hit the country in several waves; the first reaching its shores in the summer of 1918 and the second starting its progress through the country in September 1918. This second wave would prove to be far deadlier than the first, the virus having mutated into a more virulent form. On Friday 11 October 1918, the same day that Spanish influenza was reported as having arrived in London, the Treasurer, Master Robert McCall, proposed that a dinner to commemorate the tercentenary of Sir Walter Raleigh’s death be held on Tuesday 29 October 1918, which was approved by the Inn’s Parliament. This dinner proceeded as intended; the organisers and attendees undeterred by increasingly alarming reports of deaths caused by the virus.

The lack of action taken by the Inn in response to the influenza pandemic is surprising to modern eyes. Business continued as usual, Parliament continued to meet and there is no mention of the pandemic within the minutes that they produced. This inaction was not unique to the Middle Temple and was symptomatic of a lack of leadership by the central government when confronting the crisis. The department responsible for managing the pandemic, the Local Government Board (LGB), lacked authority and was short on manpower due to the demands of the First World War. They delegated the management of the pandemic to local authorities, which led to a piecemeal national response. Additionally, the LGB issued no official guidance to the country until late October 1918. They had considered issuing a memorandum on the flu in the summer but had to shelve it due to pressure to ‘carry on’ that was caused by the war.

When guidance was provided, it differed substantially from that issued by modern governments and medical professionals. Hand washing was not emphasised, disinfecting of surfaces and throat gargles were recommended instead. Social distancing was not advised unless someone was displaying symptoms, in which case responsibility was placed on the individual to go to bed immediately and stay there for three days. Theatres, cinemas and music halls could remain open, provided there was an interval of 30 minutes and the room was fully ventilated during this time. While some medical professionals advised the public to avoid crowded meetings and stuffy rooms, the wartime conditions in the country at the start of the pandemic made widespread implementation of this advice impractical and lockdowns unthinkable. The government’s priority was to avoid alarming the civilian population and to carry on as normal. To this end people were advised to maintain a ‘cheerful’ disposition lest fear, panic and depression make them more vulnerable to the illness.

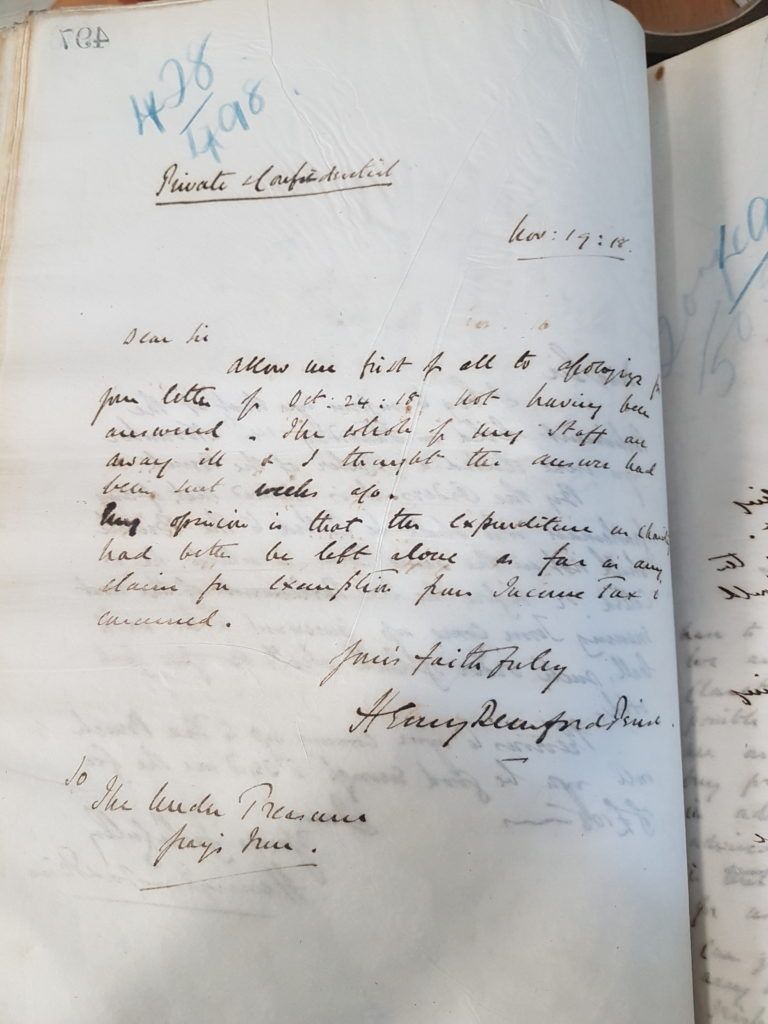

The result of this comparatively laissez-faire attitude can be found in the Society’s letter books, which contain copies of all the Treasury’s outgoing correspondence between 1850 and 2001. Monday 11 November 1918 was the peak of the second wave of the influenza pandemic in Britain and the staff of the Inn were badly affected. The Under Treasurer struggled to maintain the administrative functions of the Inn due to lack of personnel. In the first piece of correspondence referring to the pandemic, dated Monday 11 November 1918, the Under Treasurer apologises for the late reply to their letter of Thursday 24 October, which was not answered as ‘the whole of my staff are away ill’. The date of the initial letter implies that there may have been staffing issues at the Inn from as early as late October. Further letters written on Thursday 28 November and Monday 2 December show that staffing issues created by the pandemic persisted for many weeks. It is unclear whether the virus itself caused any fatalities among the Inn’s employees, but the staff books record one death during this time period.

102 years have passed since the Spanish influenza ravaged the world, and the national response to a pandemic of that scale has changed significantly in that time. Social distancing, which was not encouraged in Britain during the 1918/19 pandemic, has become one of the primary methods of controlling the spread of Covid-19, and has caused the dramatic closure of the Inns of Court for the first time in centuries.