Master John Mitchell was Called to the Bar in 1972 and made a Bencher in 2012. He was appointed a District Judge in 1999 and a Circuit Judge in November 2006, sitting in both the County Court and the Family Court in London. He retired in 2017. Master Mitchell is Chairman of the Middle Temple Historical Society.

During the Great War the damage caused to the Inn’s estate was minimal. An anti-aircraft shell missed Gotha bombers and fell through the roof of the Queen’s Room without doing more than making a hole in the floor. Bomb damage was caused to the upper floors of 1 Hare Court and a second, unexploded, bomb was found in Hare Court itself. However, there was no complacency at the resumption of hostilities in 1939. Aircraft development and the experience of civilian bombing during the Spanish Civil War and of Warsaw ensured that preparations were swiftly made. The Middle Temple organised air raid precautions and staff, residents and members volunteered to act as firefighters, wardens and first aiders. The Inn’s workmen developed an understanding of the roof structures, gas controls and water hydrants. Lectures were given on the use of stirrup pumps and the danger of gas.

However, the training went untested during the year of the ‘phoney war’, which ended on Saturday 7 September 1940. There followed raids on 56 out of the next 57 nights, during which more than 18,300 tons of bombs fell on London. On the seventeenth night, the Temple experienced the horror of modern aerial warfare for the first time.

Harold Nicholson, a resident of 4 King’s Bench Walk, spent the night of Tuesday 24 September 1940 at his office in Whitehall. He heard the drumfire of anti-aircraft batteries and wrote in his diary that when they drop into silence, ‘one hears above them, irritating and undeterred, the dentist’s drill of the German aeroplanes, seemingly overhead, appearing always to circle round and round, always ready to drop three bombs and then…crump, crump, crump somewhere’.

The next morning was cold, bright and cloudless but a pall of smoke and the smell of burning stained the air. As Nicholson reached the Temple he found water, soot and burnt paper everywhere. During the night six bombs had hit the Temple. A bomb had fallen through the roof of Inner Temple Hall, wrecking the interior. All the stained glass had been blown into Lamb Court where it lay smashed and twisted, Chambers in both Elm Court and Crown Office Row were flattened and two cornice stones from Elm Court, each weighing a ton and a half, had been blasted into Pump Court. A member of the Inn, writing under his pen-name of Cyril Hare, was to recall how ‘the mellow, placid Courts, ghost-haunted by the illustrious dead [had vanished] into ugly heaps of charred timbers and brick dust’.

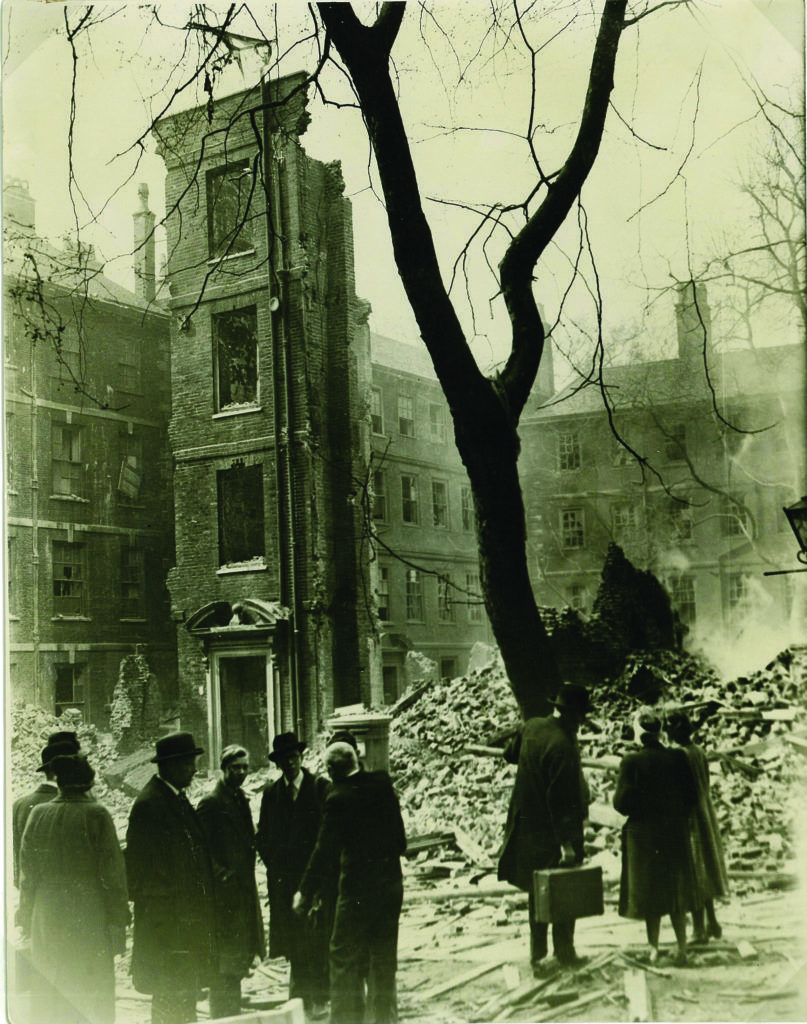

Further damage was caused on Tuesday 15 October 1940 when a parachute landmine fell in Elm Court but it was the force of the explosion rather than impact which caused widespread devastation. Fig Tree Court and Crown Office Row were all but destroyed and roofs and windows were shattered throughout the area from Lamb Building in the east, to Garden Court in the west, and from Brick Court in the north, to Plowden Buildings in the south. A huge piece of masonry was blown through the East Gable of Middle Temple Hall, smashing the gallery and badly damaging the Screen. The next day bewildered people wandered dismayed and angry over ground which was covered by a thick layer of what seemed like brown snow.

On the Sunday 8 December 1940, the Hall was thankfully spared further significant damage when a second landmine exploded immediately to its west, creating a crater 18 feet deep and 40 feet wide and all but demolishing the neo-gothic Victorian library. 50,000 dust covered books spread three feet deep over the floor were recovered and following further damage a temporary library was opened in the Common Room on Thursday 2 January 1941.

The nightly watch continued, manned not only by the staff and members of the Inn but also barristers’ clerks. In January, the Senior Warden was mobilised and recalled that his first night in the RAF was his first night of unbroken sleep for months. TF Hewlett, the Under Treasurer, did not keep a diary of the Blitz. As he later explained, ‘As the raids increased in intensity the chances of survival, either of the Temple or its wardens, appeared small and it hardly seemed worthwhile’.

The threat turned from high explosives to incendiary bombs which fell on the Inn twice in the next three months. But it was not until the clear and moonlit night of Saturday 10 May 1941 that three bombs and incendiaries caused significant damage, which was aggravated by winds and, because the Thames was at low tide, a lack of water. The Master’s House, all but the outer walls of the Church, the Cloisters and most of Pump Court were destroyed. Elsewhere fires raged in both the Cities of London and Westminster. Five Livery Halls and the House of Commons Chamber were lost and national symbols such as the Tower of London, Westminster Hall and the Abbey damaged. Buildings smouldered for days.

Thereafter further firefighting precautions were taken, including using the Fountain and the basements in Brick Court as static water tanks. Nightly watches continued but apart from some nuisance raids in 1943 and many nightly alerts, incendiaries fell only once more on the Temple. On that occasion nine buildings were damaged but the greatest threat was to the Hall. Although its cupola was destroyed, hours of firefighting saved the roof. The flying bombs and V2 rockets of 1944 also missed the Inn although buildings were further damaged when two doodlebugs exploded nearby.

The experience of night watching during this period was vividly described by an anonymous lady barrister and long term Inn resident in her post-War memoir, Middle Temple Ordeal:

Throughout those years, the inmates slept like cats with one ear open ready to distinguish the ‘alert’ from the many other sounds to be heard- the trams on the Embankment, the river craft hooting down the Thames, the screech of an owl. Five clocks striking, never in unison, the cable in the garden winding the [barrage] balloon either up or down and from daylight, several local cockerels and the trumpet sounding Reveille on the training ships.

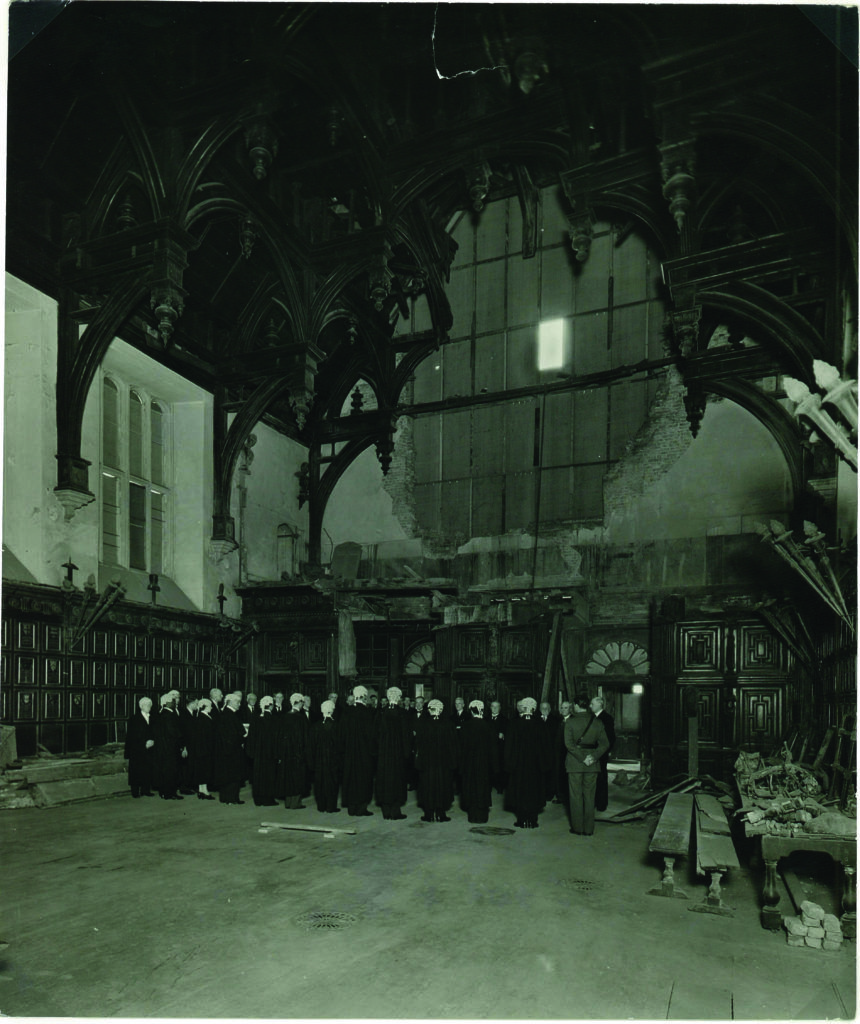

By day, life in the Temple continued albeit amid novel surroundings. The Inn kept rabbits and the Inner, hens. A cuckoo sat in a tree in Fountain Court. Wild plants and grasses including rosebay willow herb flourished in the ruins to such an extent that a visitor remarked that ‘It’s as good as Kew’. And in 1941 the Trinity Term Call was held in the ruined Hall.

The war in Europe ended on Wednesday 9 May 1945. Celebratory bonfires were lit, including one in Chancery Lane where a sober looking gentleman wearing a wing collar, encouraged by a crowd, added broken doors to the flames. Harold Nicholson too noticed the smell of bonfires as he walked back to the Temple:

Looking down Fleet Street one saw the best sight of all- the dome of St Paul’s rather dim-lit and then above it a concentration of search-lights upon the huge golden cross. So, I went to bed.

It had all been as Wellington said of Waterloo ‘the damn-nearest run thing you ever saw’. One hundred and twenty two of the 285 sets of chambers and the new library had been totally lost and all the main buildings had been extensively damaged. Timber roofs have an elasticity which helps them withstand shock but the Hall could not have survived a direct hit from a rocket. and timber is especially vulnerable to incendiaries. But the Hall and with it the Inn had survived, in part due to chance but also because of the sustained dedication of many volunteers; staff, members, residents and clerks, who acted as wardens, watchers and firemen and who maintained the life of the Inn over five years.

On Tuesday 12 December 1944 Queen Elizabeth had dined for the first time as a Bencher. Replying to the Loyal Toast she spoke of the hazards which had been overcome:

It is well to be reminded that whilst our walls may crumble, this is of small account so long as the virtues and graces for which this Inn has ever stood continue unshaken and unshakeable. It is upon their foundation that you will rebuild.

And rebuild, the Inn did.

A more detailed account of the Inn during the War and its post-war rebuilding, written by Master Eric Stockdale appears in The History of the Middle Temple. Middle Temple Ordeal has long been out of print but copies are sometimes available on Amazon.