Master Timothy Saloman was Called to the Bar in 1975 and educated in Classics and Law at Lincoln College, Oxford. A specialist practitioner in shipping law at 7KBW, he took Silk in 1993 and served many years as a Recorder of the Crown Court. He was made a Bencher in 2003 and, in 2020, Master of the House.

Among the pleasures of being the Master of the House is overseeing the Inn’s portraits, a task which allows reflection on the lives of their subjects.

Distinguished figures in the Inn’s life, present and past, are, of course, not only visible to us in portraits. They are also memorialised in the fine, oak armorial panels decorating our glorious Hall, and in our stained-glass windows, whence the coats of arms of many Middle Templars, Royalty and Peers, including Lord Carson of Duncairn, gleam down on us as we dine.

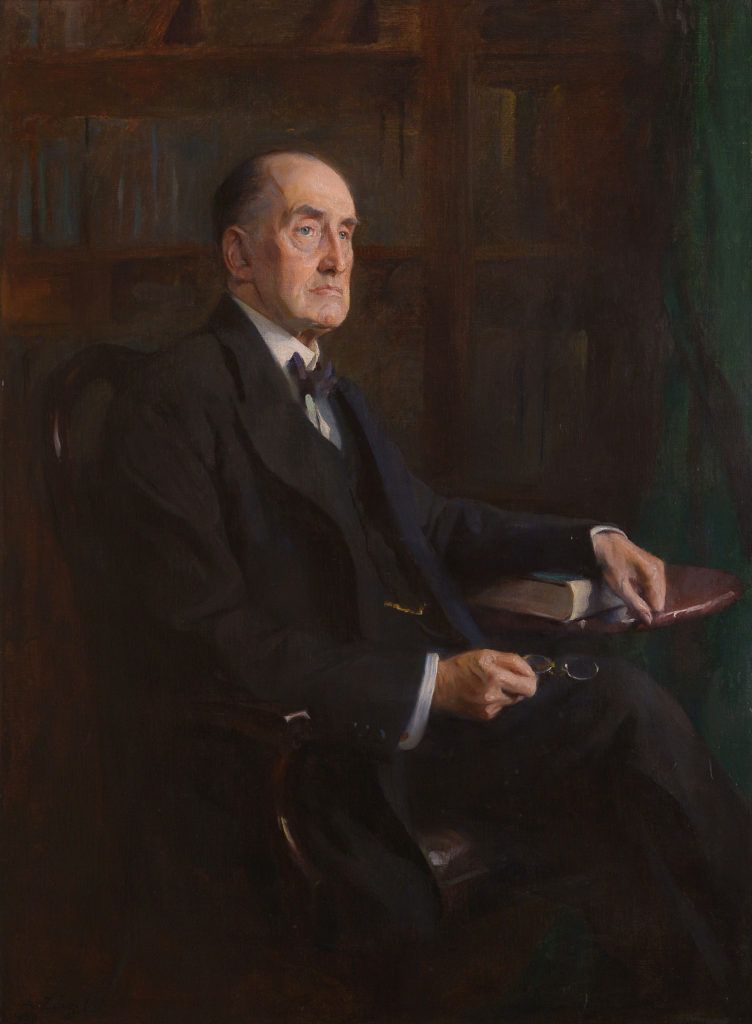

Of the Inn’s portraits, the largest and grandest are undoubtedly those of the seven Kings and Queens who dominate the west end of Hall. However, it is in and around our Bench Apartments that hang the portraits of our memorable lawyers, barristers and judges; and in the Ashley Building, where currently hangs the Inn’s portrait of Lord Carson by P.A. De Laszlo, painted in 1933.

Why, then, is Edward Henry Carson my subject?

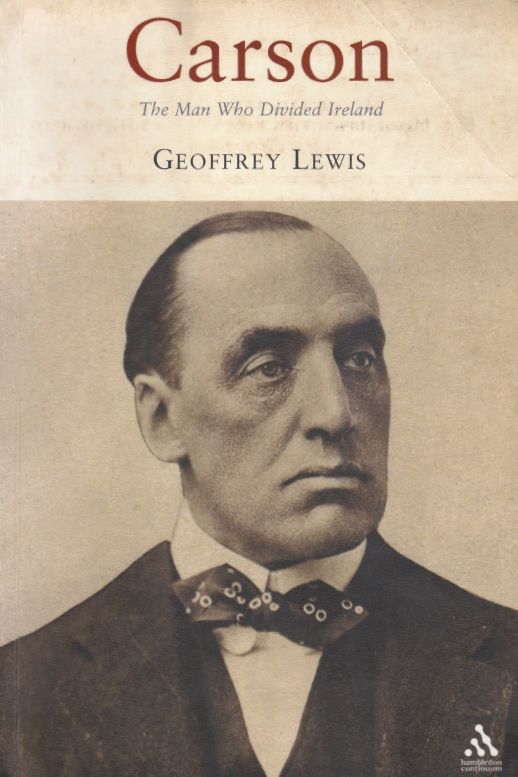

First and foremost, for us lawyers, Carson was an outstandingly successful barrister, who as an advocate achieved eminence and nationwide celebrity; first, in Ireland between 1877 and 1892, and then at our Bar, before sitting as a Law Lord from 1921 to 1929.

Second, because for all of Carson’s success in the law, it was in politics that he had the greatest impact on the nation: as the leader and champion of the Ulster Unionists’ cause, battling against the 2nd and 3rd Home Rule Bills, and securing Ulster’s status as part of the United Kingdom and its then Empire. Views on the merits of that impact sharply diverge, but in reviewing the careers of Middle Templars from our past, every impact at the highest level may command our interest, and, with Carson, his impact was colossal. One may ask: what other actively practising Middle Temple barrister or judge stands immortalised by a towering statue, in a major city, dominating its Parliament Buildings, as Carson, in Belfast, has since 1933?

An Irishman, born in Dublin, and called at the King’s Inns in 1877, Carson gained a reputation as a brilliant jury advocate and all-round barrister, famous for prosecuting agrarian crimes in prominent, politically charged cases.

He was invariably victorious and always fearless; in spite of the mob violence his cases would attract outside (and sometimes inside!) his courts. From the Parliamentary Nationalists, Fenians and agitators who deplored, but respected, these successes, Carson attracted the sobriquet ‘Coercion Carson’; during the 1880’s, he also attracted the friendship and political patronage of the society lioness, Lady Londonderry; forged a life-altering friendship with the Conservative, AJ Balfour; and, by 1889, became the youngest ever Irish QC.

In 1892, Carson was elected as the Liberal Unionist MP for Dublin University, and appointed Solicitor General for Ireland. Soon afterwards, Carson was introduced to Charles Darling QC MP, who persuaded Carson to seek re-admission to our Inn and to practise here.

‘You let me paint your name outside my Chambers’, said Darling, ‘and you’ll have five times my practice within a year’. ‘I know I won’t’, Carson said, ‘but I’ll bet you a shilling’. A year later, Darling was proved right, and Carson discharged his bet with the gift of a silver-mounted blackthorn stick, inscribed ‘CD, from EC, 1894’.

Carson’s application for English Silk, in 1894, was rejected, prompting the press to remark that this was ‘…to the ordinary intelligence, a piece of flagrant injustice’; but it succeeded in 1895 and Carson was soon engaged by Douglas, the Marquess of Queensbury, to defend him against Oscar Wilde’s libel claim, in Wilde v Douglas.

On hearing that Carson, whom Wilde considered from his Trinity Dublin days to be a worthy plodder, would be acting, Wilde reacted with amused disdain; but his bravura shrank on hearing of Carson’s reputation, saying: ‘No doubt he will perform his task with the added bitterness of an old friend’.

As everybody knows, Wilde’s claim ended in humiliating defeat for himself, and in celebrity for Carson; but Carson wanted nothing to do with the criminal prosecution that followed, vainly attempted to dissuade the Solicitor General from pursuing it and deplored the tragedy for Wilde which ensued.

In 1896, Carson co-defended in the major state trial of R v Jameson. Dr Jameson was ‘scape-goated’ and prosecuted for the failure of his ‘raid’ into the South African Transvaal, convicted under the Foreign Enlistment Act, and briefly imprisoned, but Carson successfully defended him against various civil actions, enabling Jameson to resume his career and become Prime Minister of the Cape Colony.

When Solicitor General (1900-1905), Carson led in another major state trial: Rv Lynch [1903]. ’Colonel’ Arthur Lynch, an Irish Australian and British subject, had fought for the Boers against the British, was prosecuted, convicted and sentenced to death for the offence of High Treason in breach of the 1352 Treason Act, notwithstanding that his acts were committed ‘outside the realm’.

Fortunately for Lynch, and indeed for Britain for whom Lynch gallantly fought in WW1, his sentence was commuted; but Lynch would prove to be an ominous forerunner for the later bringing of treason charges against another Irish Nationalist, Sir Roger Casement, in May 1916. No further appeal, nor mercy of any kind, was extended to Casement.

Carson acted in many other notable cases, including: R v Chapman (murder of wives and lovers by slow poisoning); Cadbury v Evening Standard [1908] where the newspaper’s allegation of Cadbury’s indifference to the use of slave labour in cocoa it purchased from San Thome was held libellous; but Carson’s cross-examination and speech led the jury to award contemptuous damages of one farthing; and Lever Brothers v Associated Press (libel) where the impact of Carson’s jury advocacy was so compelling that (as in Wilde) liability was conceded mid-hearing, and huge damages were agreed.

It was, however, the case of a 13 year old Naval cadet, George Archer- Shee, dismissed by the Royal Naval College for the alleged theft of a five-shilling postal order, that inspired Carson beyond all others. The boy consistently maintained his innocence: but how could this be undone, or the dismissal even challenged?

In a cause célèbre, later dramatised in Rattigan’s The Winslow Boy, Carson had first to surmount the Admiralty’s claim of Crown immunity and he only succeeded in the Court of Appeal, where one Lord Justice kept helpfully interrupting his opponent with: ‘Yes, yes; but where are the facts? We want the facts’.

At the hearing Archer-Shee’s evidence was rock-like and Carson cross-examined destructively, in particular undoing the postmistress’s ‘convinced’ identification evidence: the Crown surrendered, and the press celebrated the outcome as: ‘… not so much the triumph of the law, as the triumph of a great lawyer, Sir Edward Carson… Even law may be… impotent without personality’.

How did those who knew his advocacy appraise it?

For Sir F.E. Smith (later Lord Birkenhead), who appeared against and with him in several cases: ‘Carson was the greatest advocate the English Bar has produced since Erskine’; for Viscount Hailsham LC: ‘…the most brilliant advocate of his day’; for Edward Marshall Hall: ‘I have had to fight all the men who have made reputations …and you are the only advocate I have feared as an opponent’; and for Lord Atkin: ‘the greatest advocate of the lot’.

In politics, Carson’s career was devoted to maintaining the Union of Great Britain with all Ireland, and to opposing Home Rule. When that Union could not stand, he devoted his energies to the narrower objective of preserving Ulster within it.

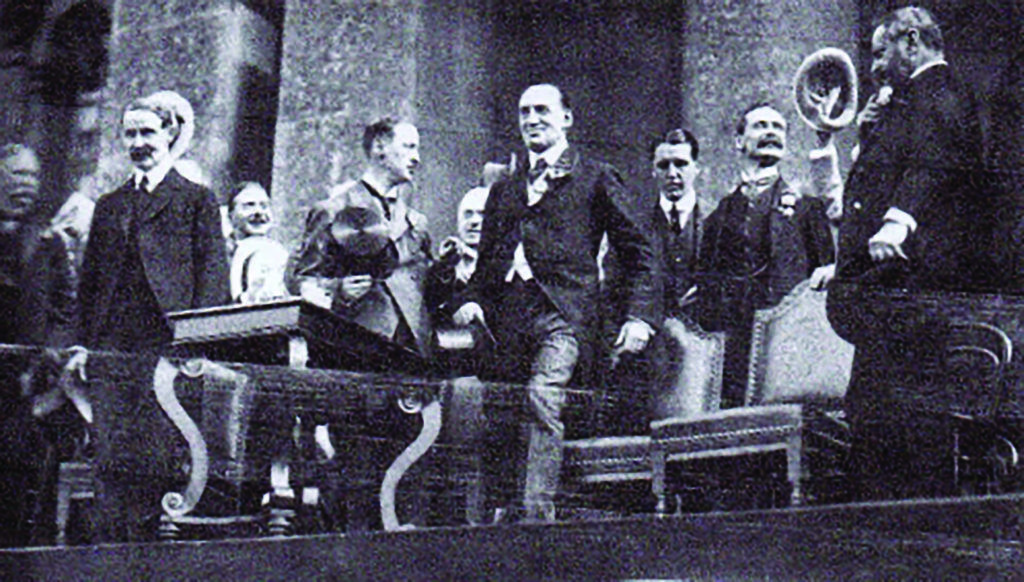

Carson forged strong relationships with Conservative leaders, notably AJ Balfour and Bonar Law. He accepted the leadership of the Ulster Unionists and in 1912 inspired 417,414 men and women to sign the ‘Ulster Covenant’. He pledged, with them, to resist by ‘any means necessary’ the imposition of Home Rule, and he condoned the running of guns to Larne, to make that pledge meaningful. By 1914, Home Rule had still not been got through and, after the war, its imposition on Ulster was unattainable. Carson’s narrower objective thus succeeded, albeit with a Belfast Parliament rather than the Westminster one that Ulster and Carson had wanted.

Carson and his impact on Ulster and Ireland have attracted differing opinions. To Ulster unionists, Carson was ‘the man who laid down everything, sacrificed everything, to come across to Ulster and help her to save herself’ (per James Craig, later Lord Craigavon). To Nationalists, Republicans and others, Carson was, for all his acknowledged charisma and power, indifferent to the prevalent desire in Ireland as a whole for Home Rule or independence, content for Ulster’s unionism to trump Irish democracy, and willing to carry resistance to virtually any length, even if that led to partition or civil war.

What people of all persuasions agree is that Carson was a formidably effective spokesman for his cause, as persuasive in the House of Commons or at Ulster rallies as he had already shown himself to be in the law, before judges and juries. Nor was Carson’s political career set back – or even stalled – by his doughty and likely illegal actions in 1913/14. By May 1915 Carson was appointed Attorney General; and in December 1916, on Asquith’s resignation, First Lord of the Admiralty.

In 1932, the Inn recognised Carson by commissioning Philip de Laszlo to paint him. A leading portraitist of the day, he declared his delight at painting ‘one of the most interesting and picturesque men of our times’. Carson had already twice been painted by that other great portraitist, Sir John Lavery, but neither work had pleased him, and neither possesses the mellow serenity, grace and obvious likeness of this rendering by de Laszlo. In 1958, a charming statuette of Carson enhanced our memorabilia. Alas, that was stolen many decades ago, leaving us to treasure our portrait all the more.

On Carson’s death, Britain accorded him a state funeral with full pomp. Conveyed to Belfast by warship, his coffin draped in the Union Jack was carried to St Anne’s Cathedral, where the choir sang his favourite hymn:

I Vow to Thee, My Country. He remains the only person buried there; and, at Stormont, his statue retains today its solitary, lofty domination over Parliament Buildings that he hoped would never be required.