Oscar Wilde had good cause not to like Middle Temple – or at least its members. His greatest prosecutor and the judges before whom he appeared were all distinguished Middle Templars. It is ironic that each is known today as much for their connection with Wilde than their other considerable achievements. Wilde himself did not hold a high opinion of lawyers in general. ‘Only lawyers and mental defectives are automatically exempt from jury duties’, he wrote.

In 1894, Oscar Fingal O’Flahertie Wills Wilde had consulted a fortune teller in London called ‘Sybil of Mortimer Street’. She told him ‘I see a very brilliant life for you up to a certain point. Then I see a wall and beyond that wall I see nothing’.

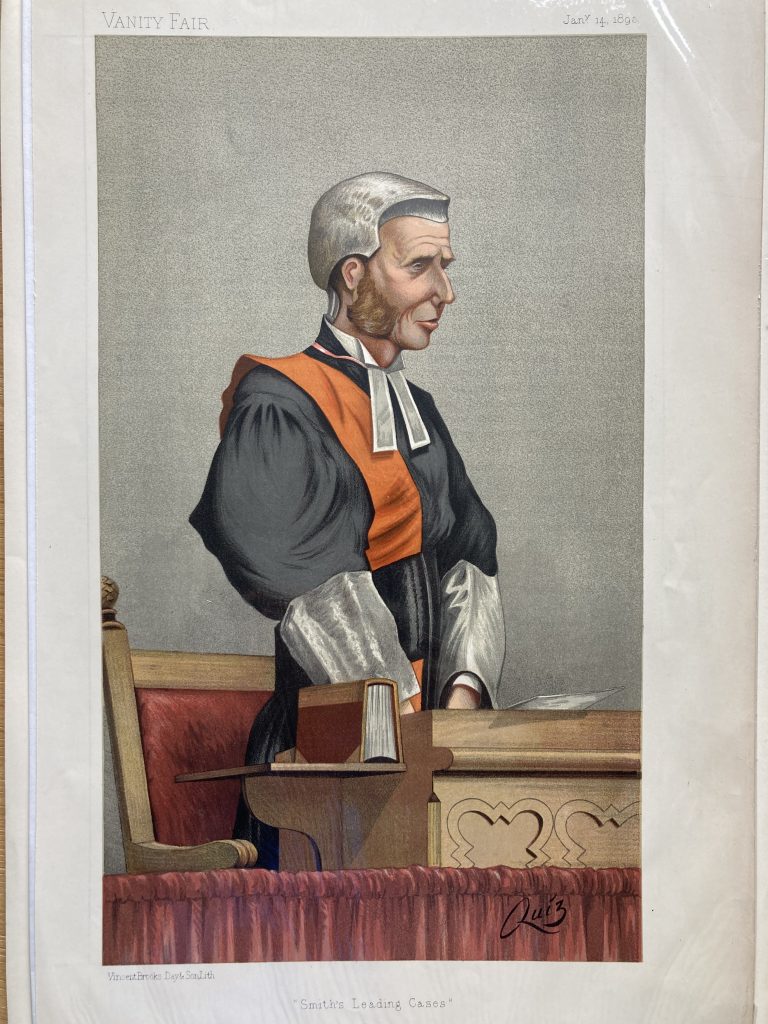

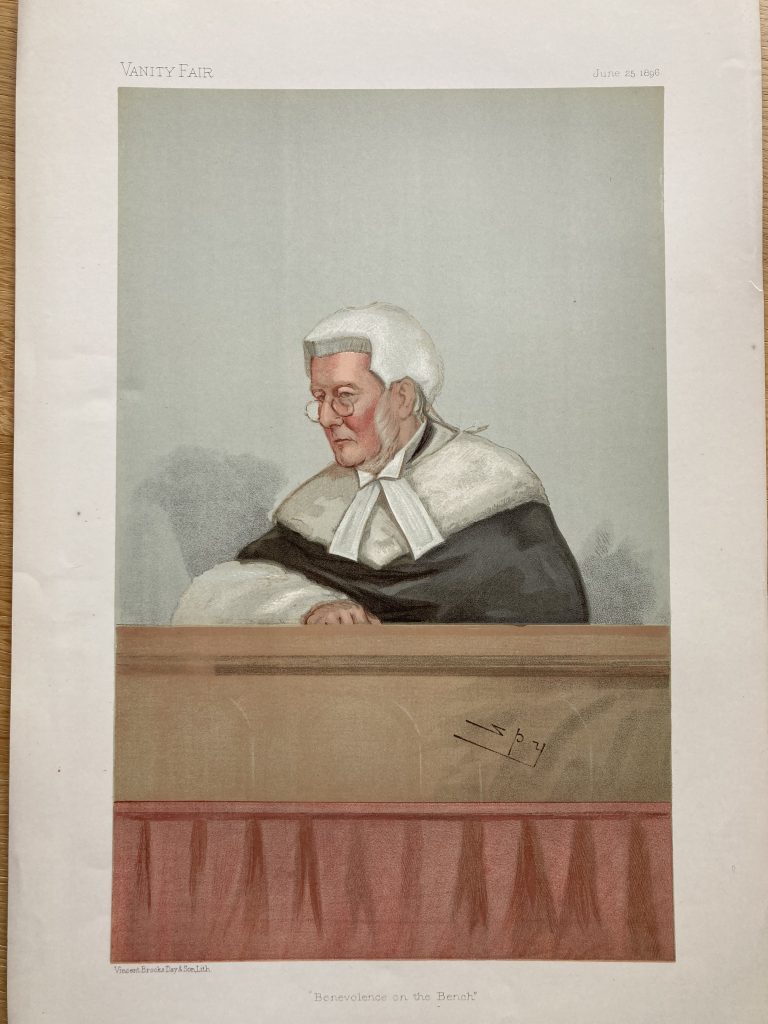

Let us go back in time, just over 125 years and visit ‘the wall’. It is now Saturday 25 May 1895. The Honourable Mr Justice Wills is sitting in his Chambers adjacent to Court No.1 at the Old Bailey, having just been informed that the jury have reached verdicts in the case of Regina -v – Wilde. The judge had been Treasurer of Middle Temple in 1892. Members of the Inn today can see the silver Hanap Cup and Cover which he donated in 1894. The son of a Birmingham solicitor, he went to University College in London. Called to the Bar in 1851, Wills took Silk in 1872 and was appointed to the High Court Bench in 1884. He died in 1912 and is perhaps best remembered as one of the original members of the Alpine Club, ascending the Wetterhorn in 1854.

But let the Judge take over the account.

‘Three sharp raps on the door to Court No.1 and it opens into the large, panelled Courtroom. All rise as I enter and take my seat. I see that Lord Alfred Douglas, the recipient of those obscene love letters from Wilde addressed to ‘My Darling Boy’, is sitting in the front row of the reserved seats. The Attorney General, Sir Frank Lockwood QC, is present for the Prosecution and there is Wilde’s counsel, Sir Edward Clarke QC, with his shaggy eyebrows and distinctive mutton-chop side whiskers. The Clerk to the Arraigns is on his feet ready to take the verdicts. The prisoner stands in the dock surrounded by warders.

‘Members of the jury, on the indictment alleging offences of gross indecency against Oscar Wilde have you agreed upon your verdicts?’

‘We have’.

‘On count 1 do you find the prisoner at the bar guilty of an act of gross indecency with Charles Parker at the Savoy Hotel on the night of his first introduction to him?’

‘Guilty’.

And so, all the verdicts followed suit, and richly deserved too.

I directed that the co-accused be brought up from the cells. Alfred Taylor, a particularly nasty piece of work, minced his way into the dock and stood beside his erstwhile friend. I addressed them both.

‘Oscar Wilde, the crime of which you have been convicted is so bad that one has to put stern restraint upon oneself from describing, in language which I would rather not use, the sentiments which must rise in the breast of every man of honour who has heard the details of these two horrible trials… It is no use for me to address you. People who can do these things must be dead to all sense of shame. And one cannot hope to produce any effect upon them. It is the worst case I have ever tried. That you, Taylor, kept a male brothel it is impossible to doubt. And that you, Wilde, have been the centre of a circle of extensive corruption of the most hideous kind among young men, it is equally impossible to doubt. I shall under such circumstances be expected to pass the severest sentence that the Law allows. In my judgement, it is totally inadequate for such a case as this. The sentence of the court is that each of you be imprisoned and kept to hard labour for two years.’

Cries of ‘shame’ and ‘oh, oh’ were heard from the back of the court. Wilde had the temerity to speak out.

‘And I? May I say nothing, my Lord?’ said Wilde.

I waved my hand to the warders to hurry the prisoners to the cells. It is most unseemly for prisoners to seek to address the judge once a sentence has been passed upon them. I thanked the jury for their labours and the court rose’.

So ended his trial. Wilde was to write later to a friend, ‘The two great turning points in my life were when my father sent me to Oxford and when society sent me to prison’.

Certainly, prison was a turning point. Wilde, now 40 years old, became a convict, thus ending the meteoric career of a playwright who had become society’s darling with his dazzling West End stage plays.

His acerbic wit is with us today, still as biting and apposite as it was over a century ago. Let a few examples suffice.

‘A cynic is a man who knows the price of everything and the value of nothing.’

‘If one tells the truth, one is sure, sooner or later, to be found out’.

‘I never travel without my diary. One should always have something sensational to read in the train’.

‘One should never trust a woman who tells one her real age. A woman who would tell one that would tell one anything’.

So, who was this man whose life was a series of contradictions?

Oscar Wilde was born on 16 October 1854 at 21 Westland Row in Dublin. His parents were themselves exceptional: Sir William Wilde, knighted for his skill as a prominent ear and eye surgeon, and inventor of Wilde’s incision for dealing with infections of the ear, and his mother Lady Speranza Wilde, a femme formidable, was a poet and talented translator of French novels. They entertained the great and the good at their home in Dublin.

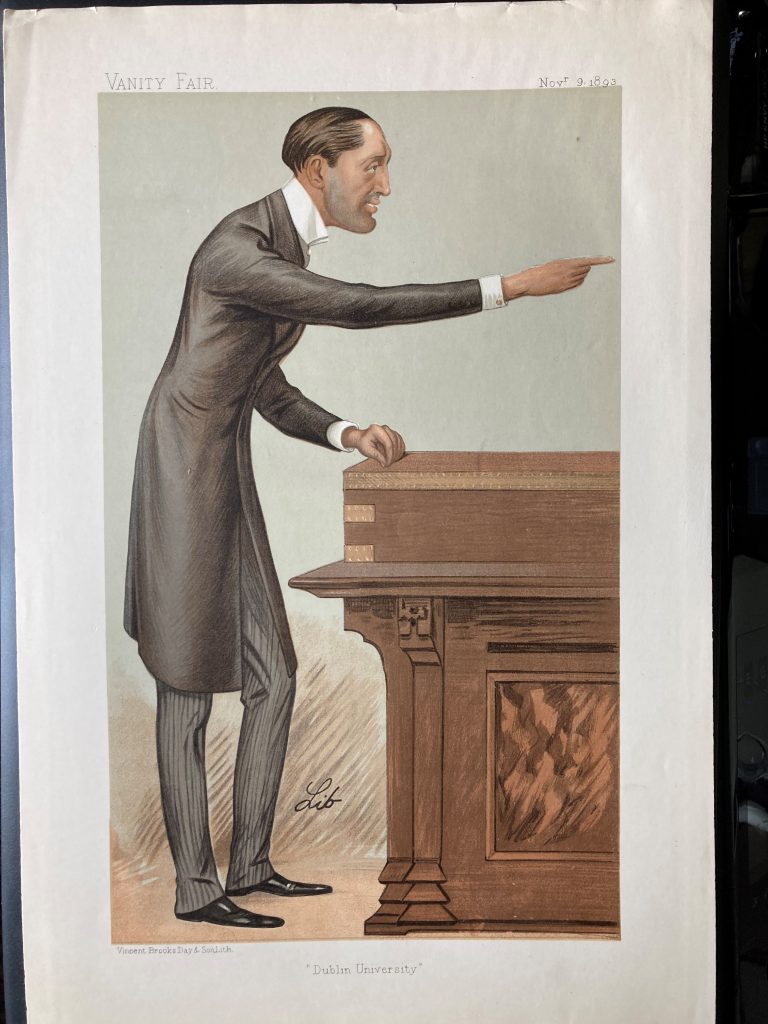

Wilde and his elder brother Willie went to school in Enniskillen. Then in 1871, he won an Exhibition to Trinity College Dublin where he was friends with Edward Carson, who was admitted to Middle Temple in 1875 and became one of its most illustrious Benchers in 1900. In 1874 Wilde went up to Magdalen College Oxford.

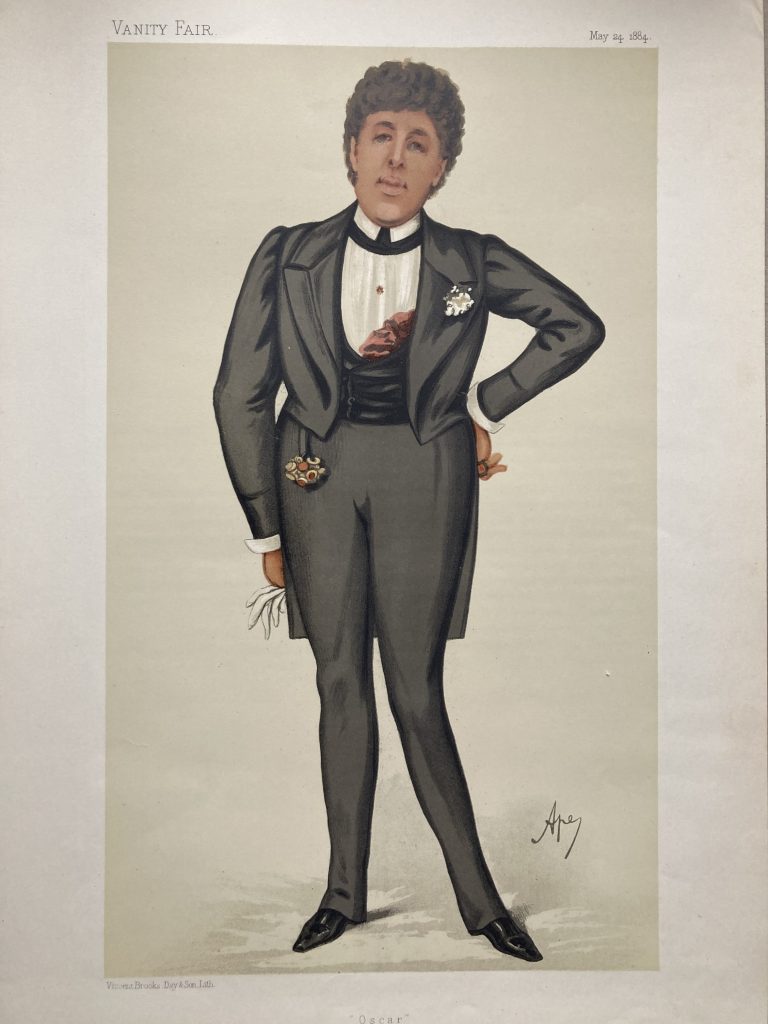

On Saturday 24 May 1884, Wilde’s caricature by ‘Ape’ (as the artist Pellegrini was known) appeared in the society magazine Vanity Fair. The short history accompanying it tells pithily of his career to date.

‘Oscar, the younger son of the late Sir William Wilde, archaeologist, traveller and Queen’s Surgeon in Ireland, won the Berkeley Medal for Greek in Trinity College, Dublin and a Scholarship. Migrating to Magdalen College Oxford he took two “Firsts” and the “Newdigate”. Then he went wandering in Greece; and, full of a Neo-Hellenic spirit, came back to invade London. He invented the aesthetic movement. He preached the doctrine of possible culture in external things. He got brilliantly laughed at, and good-naturedly accepted. In 1881 he published a somewhat startling volume of poems, and at once went to America to preach his gospel of culture. Then, as an itinerant art-apostle, he wandered from New York to San Francisco, lectured to all sorts and conditions of men, produced a play, and came back to London. Suddenly he gave up dado-worship for dandyism, cut his long locks, and accepted life. He is a sayer of many smart things, and has a rare flow of thoroughly Irish wit and an excellent notion of the advantage that may accrue to any man from drawing attention to himself anyhow.

He has lived through much laughter, in which he has always joined. He has many disciples, and is of opinion that “imitation is the sincerest form of insult”. He is twenty-eight years old, comes of a literary family, and is essentially modern. He is to be married next week.’

That year Wilde married Constance Lloyd, the wealthy and attractive daughter of a Dublin Queen’s Counsel and they took a house in Tite Street in Chelsea. In 1885 his first son Cyril was born, and the next year a second son, Vivian.

From the mid-1880s, he was writing prolifically and profitably for the stage, which included Lord Arthur Savile’s Crime in 1887, The Picture of Dorian Gray in 1890, Lady Windermere’s Fan in 1892, A Woman of No Importance in 1893 and in 1895, The Importance of Being Ernest.

But by June of 1891, Oscar had met ‘Bosie’, the subject of his lifelong infatuation, namely Lord Alfred Douglas, third son of the Marquess of Queensbury. As he famously remarked –

‘I can resist anything except temptation’. Bosie was something he could not resist.

By now his latent proclivities were no longer suppressed. In 1892, he was meeting young rent boys and indulging in homosexual activity with them in The Savoy Hotel and even at his home in Tite Street. By the Spring of 1893, he was being blackmailed by some of his young male acquaintances and was now living away from home. He had thrown caution to the winds, and in 1894 the seeds of his destruction were sown. Lord Queensbury was threatening to disown his third son unless he ceased his association with Wilde.

On Valentine’s Day 1895, took place the first performance of what was to become Wilde’s best loved play, The Importance of Being Ernest. Lord Queensbury had been prevented from entering the theatre to make a scene. But, four days later, he left a card at Wilde’s London club – The Albemarle – on which he had written ‘To Oscar Wilde posing as a somdomite’ [sic].

Wilde had once written ‘A man cannot be too careful in the choice of his enemies’. He should have followed his own advice. But he felt his honour was at stake, so launched proceedings against Queensbury for criminal libel. He did not know that the defendant was gathering damning evidence against him. Queensbury had come into possession of letters Wilde had sent Lord Douglas in 1893 in which he had written ‘You are the divine thing I want, the thing of grace and beauty’.

Wilde consulted a solicitor who perhaps sensed a spectacular case and unwisely urged prosecution. He must surely have known that all was not as it seemed. He knew that Robbie Ross – who had referred Wilde to him – was a homosexual, and that there was great intimacy between Wilde and Bosie. But the solicitor chose to accept the assurances which Wilde repeatedly gave him and did not probe beneath the surface. Had he done so he might have discovered the unsavoury truth of the ‘rough trade’ uncovered by the Marquis of Queensbury and used so effectively in the cross examination of Wilde at the criminal libel trial.

In March 1895 Wilde launched his action. It was a fateful step. On learning that his erstwhile friend from Trinity College, Edward Carson QC, was to cross examine him in Court Wilde said, ‘No doubt he will perform his task with the added bitterness of an old friend’.

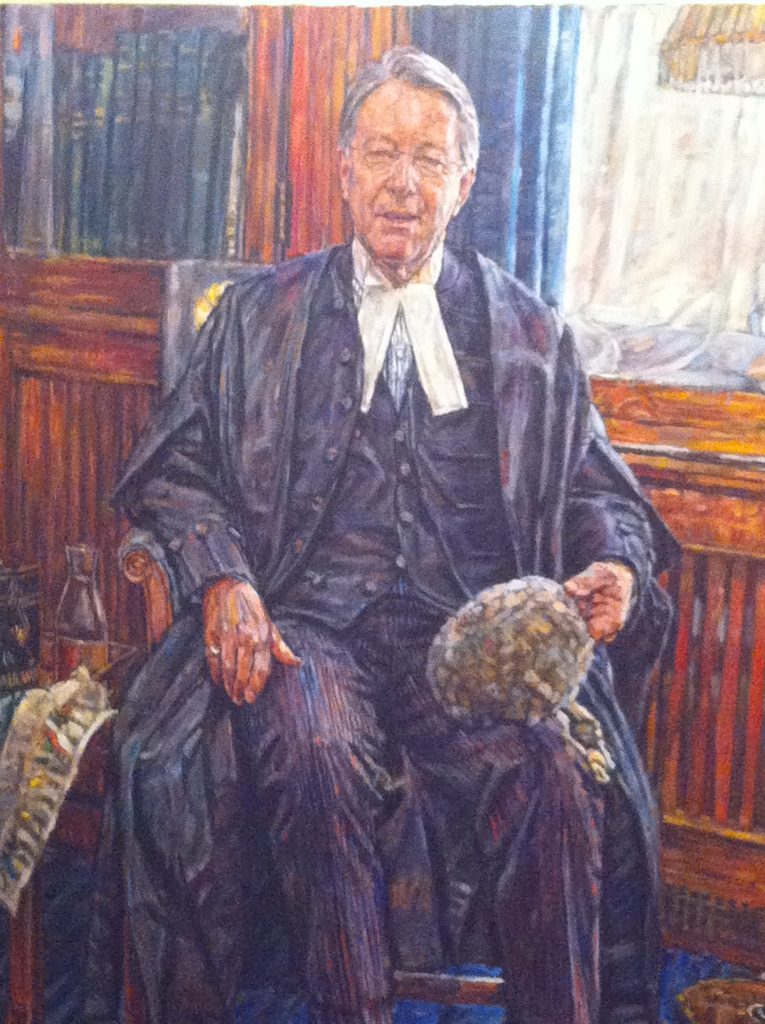

Carson, like Wilde, had been born in 1854 to affluent middle class parents and they lived only streets apart in Dublin. Carson was a pre-eminent politician as well as a barrister. He would become Leader of the Irish Unionists, wanting the whole of Ireland to remain under British rule. He held Cabinet Office positions and was First Lord of the Admiralty in the First World War. As a lawyer, he became Advocate General, Solicitor General and a Law Lord, dying in 1935.

The Judge trying the case, Mr Justice Henn Collins, was Called to the Bar of Middle Temple in 1867, took silk in 1883 and became a High Court Judge in 1891. He would become Treasurer of Middle Temple in 1905. Collins donated to the Inn a two handled Cup and Cover in 1907 which is still housed in the Inn’s extensive Silver Collection. He went on to become Baron Collins and Master of the Rolls.

The Judge sent a message to Carson after Wilde’s first trial: ‘I never heard a more powerful speech nor a more searching cross examination. I congratulate you on having escaped the rest of the filth’.

Carson’s cross examination certainly put in train the proceedings which would later see Wilde imprisoned. Perhaps Wilde thought he could fence with Carson and deflect the vitriol Carson directed at him. In the witness box, Wilde was on good form and undoubtedly scored points off Carson.

When Wilde had cause to mention his preference for iced champagne which he took – he said – contrary to his doctor’s orders, Carson snapped;

‘Never mind your doctor’s orders’.

‘I never do’ – came the riposte.

When Carson asked him if he had written some of the purple passages in the novel The Picture of Dorian Gray, Wilde said –

‘I have the honour to be the author’.

Carson then recited some verses which appeared in Dorian Gray and said with a sneer –

‘And I suppose you wrote that also, Mr Wilde?’

To which Wilde replied very quietly –

‘Oh no, Mr Carson, Shakespeare wrote that’.

Carson went scarlet with embarrassment.

When asked about his relationship with Alphonse Conway, a young lad who sold newspapers on the pier at Worthing, Wilde replied –

‘It is the first time I have heard of his connection with literature’.

But it was when Carson turned to non-literary matters that he delivered the lethal blows.

‘Did you ever kiss that servant, Grainger?’ he asked.

‘Oh dear me no! He was unfortunately extremely ugly’.

Carson went in for the kill –

‘You mean the only reason you did not kiss him is because he was ugly?

The die was cast.

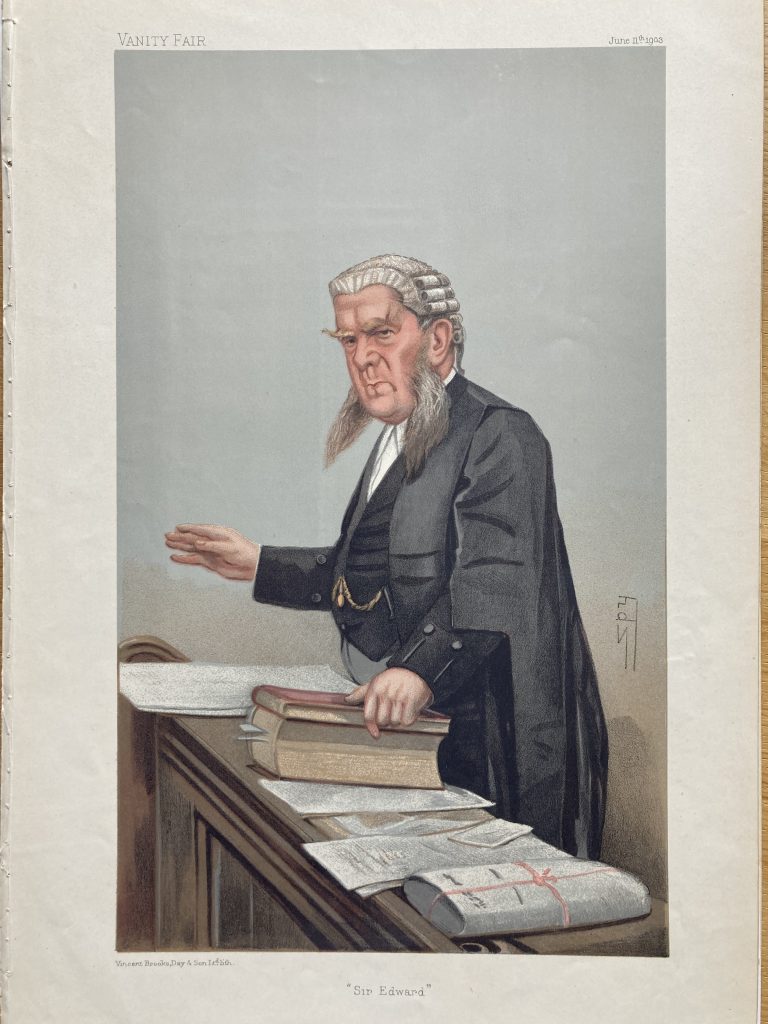

Carson then made his opening speech for the defence. He said he was now going to bring forward the young men who would testify to shocking acts with Wilde. It was too much for Wilde’s counsel, Sir Edward Clarke QC, who saw only too well and too late where the wind was blowing.

Sir Edward asked for an adjournment. Wilde was told that the trial could be kept going to give him time to leave the country and get to France. Wilde would not go. Sir Edward had to concede in the face of the inevitable evidence that the defendant was justified in claiming that Wilde had posed as a sodomite. The judge instructed the jury so to find. Cheers met the verdict.

The criminal prosecution of Wilde was bound to follow. The Criminal Law Amendment Act of 1885, enacted some ten years earlier, for the first time prohibited indecent relations between consenting males, in public or in private. Understandably, it became known as ‘The Blackmailer’s Charter’. Edward Carson, Wilde’s nemesis, wanted nothing to do with the subsequent criminal proceedings and tried in vain to persuade the Solicitor General not to prosecute. On the other hand, Queensberry threatened to go public on his suspicions about the close relationship between his eldest son Francis and Lord Roseberry if Wilde was not prosecuted. In the event Wilde was put on trial.

At his trial in April 1895, before Mr Justice Charles at the Old Bailey, Wilde admitted that he knew the boys who had testified but denied that he ever had indecent relations with them. In cross examination he spelled out his defence when asked about his letters which referred to ‘the love that dare not speak its name’. He said:

‘It is the great affection of an elder for a younger man as there was between David and Jonathan, such as Plato made the very basis of his philosophy, and as such you find in the sonnets of Michaelangelo and Shakespeare… In this century it is much misunderstood and on account of it I am placed where I am now… It is beautiful, it is fine, it is the noblest form of affection. There is nothing unnatural about it.’

At the end of his peroration the public gallery broke into applause.

The rest of the cross examination went steadily downhill. He denied the evidence of the hotel staff and all impropriety with the boys.

‘Why did you take up with these youths?’

‘I am a lover of youth’.

‘So you would prefer puppies to dogs and kittens to cats?’

‘I think so. I should enjoy, for instance, the society of a beardless, briefless barrister quite as much as that of the most accomplished QC’.

Wilde seemed oblivious to the fact that his clever answers were likely to alienate the jury.

In his closing speech, Sir Edward Clarke said the boys were unreliable proven blackmailers who had superimposed wicked lies on what was true. He submitted ‘that Wilde was undoubtedly taken in by them, was evidence of imprudence not crime’.

No doubt swayed by Clarke’s eloquence; the jury could not agree. At the retrial the Attorney General, Sir Frank Lockwood, appeared for the prosecution. Clarke’s plea to the new jury was that ‘it was inconceivable that Wilde would have subjected himself to possible prosecution by charging Queensberry with libel, if he had himself been so vulnerable’.

As we have seen, the jury took a very different view.

To add insult to injury, Wilde was adjudicated bankrupt on the petition of Queensberry on Monday 26 August 1895. He was eventually released from prison on Wednesday 19 May 1897. His mother had died in 1896, his wife in 1898 and his brother in 1899.

Wilde himself died in the Hotel d’Alsace in Paris on Friday 30 November 1900. He was aged 46. Tradition has it that, as he lay dying in the cheap hotel bedroom, he said to a friend:

‘This wallpaper and I are fighting a duel to the death. Either it goes or I do’.

The wallpaper – or rather the cerebral meningitis – won. He was buried in Pere Lachaise Cemetery in Paris.

It is ironic that years before, Wilde had written lines in The Importance of Being Ernest relating to Jack’s supposedly dead brother:

Jack: ‘He seems to have expressed a desire to be buried in Paris’.

Reverend Chasuble: ‘I fear that hardly points to any very serious state of mind at the last’.

I think Wilde would have thought that a fitting epitaph.

The myth which arose about Wilde was that the dazzling playwright was hounded to his death by the authorities because he was homosexual. That was true in part. But as Wilde himself remarked, ‘the truth is rarely pure and never simple’.

He could have ignored Queensberry’s calling card – but probably would have faced repeated accusations by the unbalanced peer who claimed he only wanted to protect his son from vice. Wilde persisted in lying to his criminal team. He knew the truth. He had the opportunity to flee abroad but chose rather to brazen it out. He paid the price for his folly.

In one of his greatest works, The Ballad of Reading Gaol – the gaol where he was incarcerated – Wilde wrote:

‘Some love too little, some too long, Some sell, and others buy;

Some do the deed with many tears, And some without a sigh:

For each man kills the thing he loves, Yet each man does not die.’

He must have reflected that he had killed the thing he loved. He had destroyed the devotion, trust and loyalty of those who truly loved him and so misfortune, disgrace and imprisonment inevitably overtook him.

These days, we would be more forgiving of his sexual attitudes and more praising of his literary talents. But there is no escaping the fact that his adult life became one of deceit and promiscuity. It was not just a discrete affair with Bosie. He abandoned his forgiving wife and sons and openly sought out young men from a very different background.

In The Importance of Being Ernest one of his characters says:

‘I hope you have not been leading a double life, pretending to be wicked and being good all the time. That would be hypocrisy’.

Wilde himself was indeed guilty of leading a double life. But he was guilty of more than hypocrisy. He sought to put himself above the Law by lying on oath in the face of overwhelming evidence. Perhaps he thought he could outwit the lawyers and mesmerise the juries. Sadly for him, he was wrong.

But now, some 125 years after his trial, let him have the last word – as he usually did:

‘There is only one thing in the world worse than being talked about – and that is not being talked about’.

So it is that he is still talked about – as are Middle Temple’s distinguished lawyers who proved in the end to be too good for the brilliant wit.

Master Paul Worsley

Bibliography

Notable British Trials of OW Ed. H. Montgomery Hyde 1948

OW by St John Ervine 1951

I Give You OW by Desmond Hall 1965

Complete Works of OW Intro. by V Holland 1976

Lord Alfred Douglas by H. Montgomery Hyde 1984

More Letters of OW Ed. Rupert Hart-Davis 1985

OW by Richard Ellmann 1987

Wilde’s Devoted Friend – Ross by Maureen Borland 1990

Bosie by Douglas Murray 2000

All photos are Vanity Fair prints – copyright to Vanity Fair

Master Paul Worsley has spent 50 years in Crime. Called in 1970, he took Silk in 1990 and became a Judge at the Old Bailey in 2007, sitting there for ten years. He was an Astbury Scholar and Reader in 2015. His son and daughter are both Middle Templars. His first book was The Postcard Murder, based on an Old Bailey Trial in 1907.