Steven Powles QC is head of Doughty Street International and specialises in international crime and extradition. He has appeared before international criminal tribunals in The Hague in cases relating to Kosovo, Kenya, DRC, and Afghanistan, and also acted in proceedings before the Special Court in Sierra Leone.

It began on a cold and wet September day. I was waiting in central London for an Uber to take me to court for one of those heavy and draining trials. An email from chambers popped up on my phone: ‘Anyone interested in applying for job in Seychelles?’. I knew the answer even before reading the message – and a couple of weeks later, I heard I had been shortlisted. I would be part of a team working on money laundering and corruption cases. My application was successful.

A former colony of the UK, the Seychelles gained its independence in 1976. Its first president, James Mancham, and the man who deposed him after just one year, Albert René, were not just both lawyers, but Middle Templars too. After 15 years of one-party rule, René announced free elections in 1992, and though Mancham returned to contest them, he prevailed. A constitution enacted the following year belatedly guaranteed pluralism and democracy; among those sent by the Commonwealth Secretariat to help with its drafting was another member of Middle Temple, Master Geoffrey Robertson.

Thanks in part to its staggering natural beauty and a thriving offshore financial services industry, Seychelles has a higher per capita income than any other country in Africa. At least half that money comes from high-spending tourists, who swim and snorkel around its 115 coral and granite islands throughout the year, but it is not all pampered luxury. As you would expect in any paradise, there is trouble too – and it is quite serious. Heroin users make up a larger proportion of the population than in any other country on earth. Up to one in ten of the country’s adults – some 6,000 people – are said to be addicts.

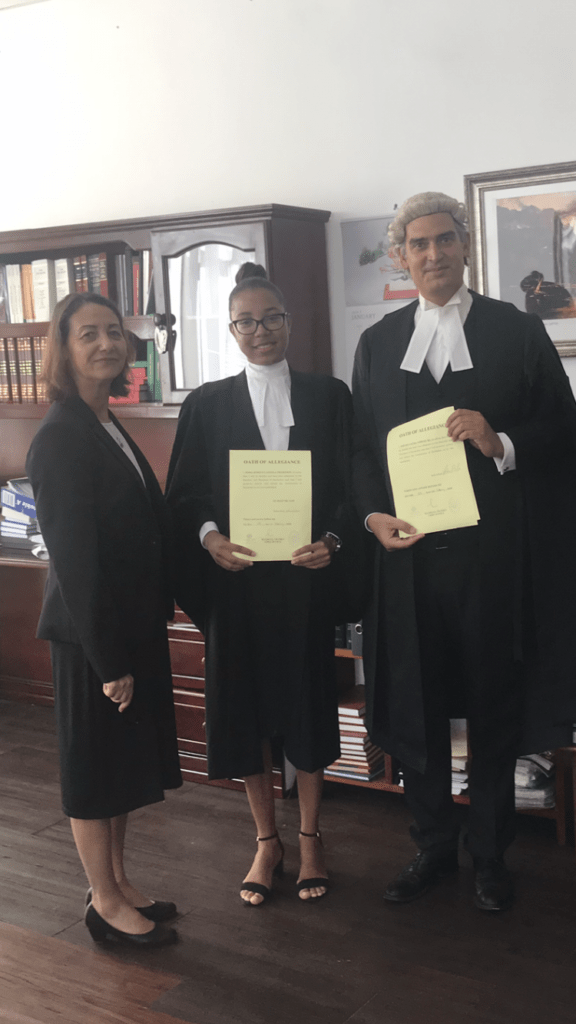

Alongside a young Seychellois lawyer, Ms Nissa Thompson, I was sworn in as a State Counsel in the Attorney General’s Chambers by the first female Chief Justice, Master Mathilda Twomey, on Tuesday 11 February 2020. Our work then commenced in earnest. We set up a unit to deal predominantly with proceeds of crime cases and Mutual Legal Assistance requests. Alongside an experienced Indian lawyer who’s also become a good friend, Mr Jayaraj Chinnasamy, I have brushed up on lessons learned with Middle Temple advocacy training and have helped teach junior prosecutors how to present and argue those cases that go to court.

My intention was initially to travel back and forth from London, but that plan – along with so much else – changed after the WHO declared a global Coronavirus pandemic on Wednesday 11 March 2020. Even before that date, the country had instituted precautions. When I flew in at the beginning of February, people arriving from areas of high infection were already being screened, and within days of the first two confirmed cases in Seychelles, on Thursday 14 March 2020, decisive steps were being taken to control the spread of infection. Courts were closed to all but emergency matters, flights in and out of the country ceased to operate, and quarantine facilities were established. To the government’s enormous credit, the consequence is that just 11 people are known to have caught the virus. No one has died.

It has been heart-breaking to watch the pandemic rage with so much violence through the UK. To see the daily death-toll rise and to admire from afar the brave effort of front-line workers to keep the numbers down. Colleagues have at least been sympathetic. When news reached Seychelles about the controversy over Dominic Cummings’ behaviour during the lockdown, I was asked with a smile if the UK needed any help from the African Union in training government officials how to respect the rule of law. As with many good jokes, the humour stung.

Even on these islands, a tiny string of outposts 1,000 miles off the African coast and twice as far from India, it is impossible not to notice the changing world order. When I arrived, the British government had just celebrated Brexit Day, and yet, the position I was about to start was being funded by the EU. The British High Commission has done outstanding work over the years, particularly with prosecuting and combating piracy; while it worked tirelessly during Covid-19 to repatriate tourists from Seychelles before airports closed, the Indian government and China’s Jack Ma Foundation were sending medical aid into the country. India is also donating generously to build a new magistrates’ court complex and offices for the Attorney General’s Chambers. But in a country where the first two presidents were both London educated barristers and members of the Middle Temple, the legal heritage it shares with other members of the Commonwealth remain strong. Many of my colleagues are Indian lawyers, and the lawyer honoured with a statue outside the offices where I work is the great Mahatma Gandhi. As the 50th anniversary of independence approaches in 2026, these connections should be celebrated – and it would be especially befitting if the Inn could mark its deep links to the Seychelles in some suitable way.