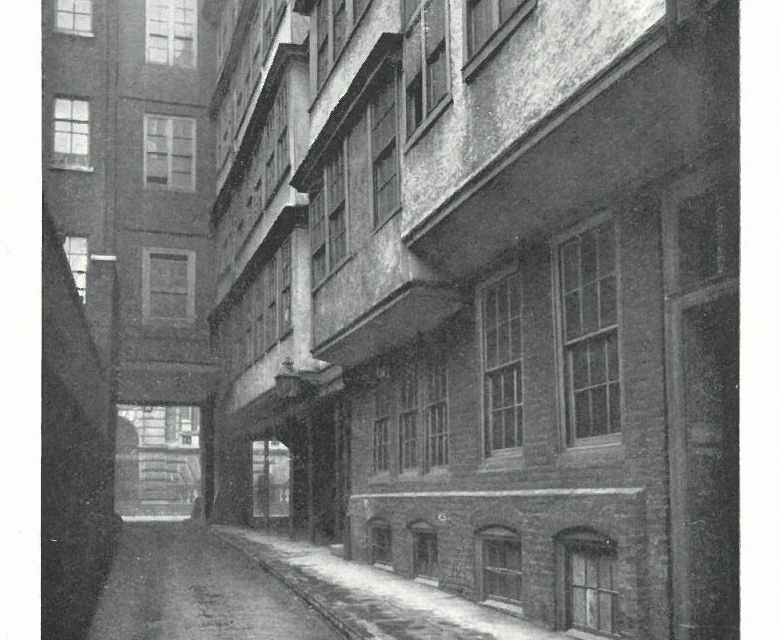

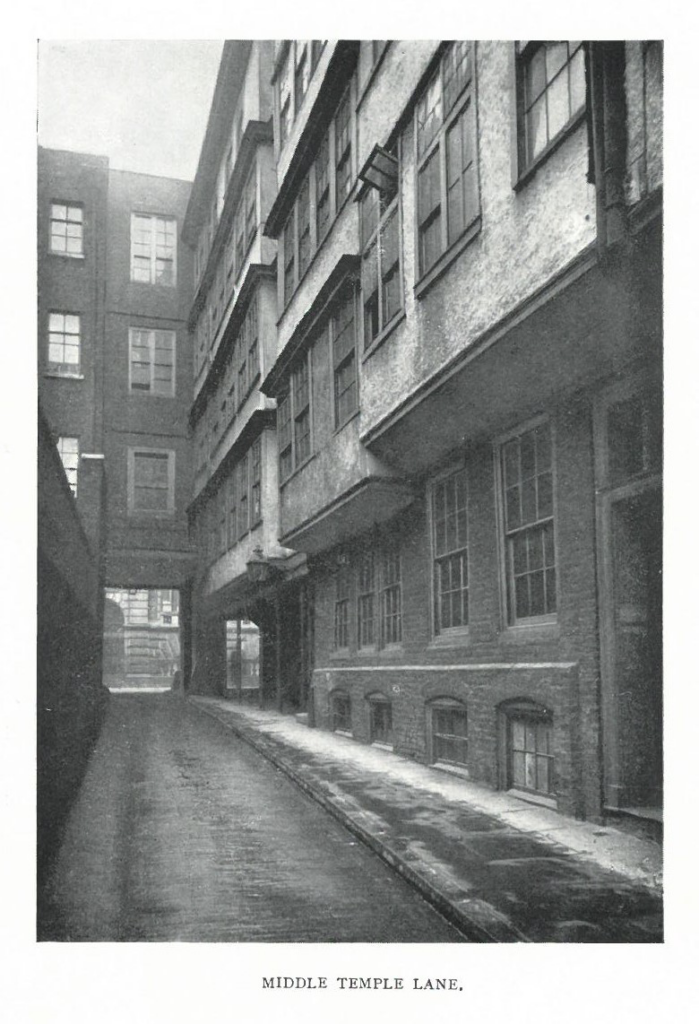

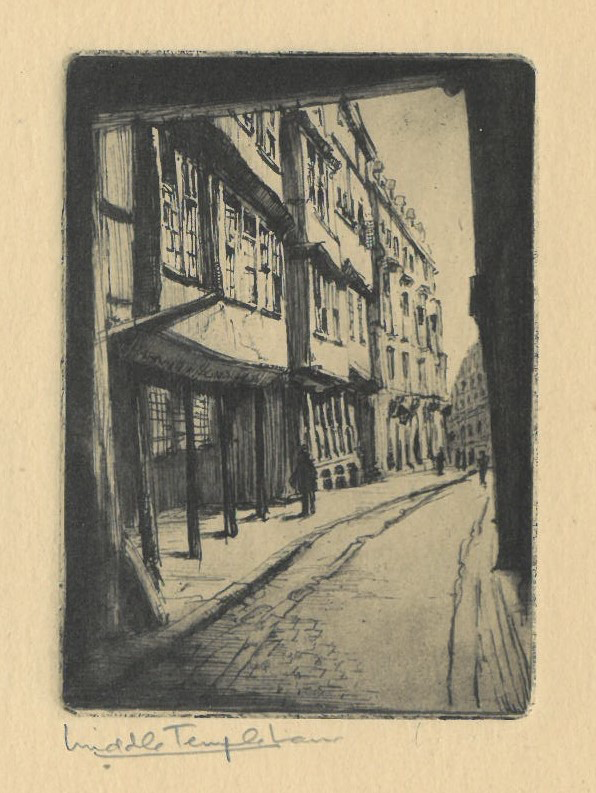

‘There’s a man lying in one of them entries down the lane, and [the porter] thinks he’s dead. Likewise he thinks he’s murdered’…. The entry was a cold and formal thing of itself; not a nice place to die in, having glazed white tiles for its walls and concrete for its flooring; something about its appearance in that grey morning air suggested to Spargo the idea of a mortuary. And that the man whose foot projected over the step was dead he had no doubt.

The lane in question was Middle Temple Lane. Those lines do not of course describe a real murder within our boundaries but are from the opening passages of The Middle Temple Murder by J S Fletcher, published in 1918 by Ward, Lock & Co (publishers of the early Sherlock Holmes books). I doubt if many of my readers will have heard of the book, or of its author, notwithstanding that he was a prolific writer in the so called Golden Age of Detective Fiction and that the book marks an important point in the history of the genre.

Let me first outline the beginning of the plot, which is set in the summer of 1912. Frank Spargo, a young sub-editor in Fleet Street (at a time when Fleet Street was Fleet Street), leaves his office for the night at 2am and begins his walk home along Fleet Street; it was a regular walk, and he was familiar with the regulars along the way. As he approached the entrance to Middle Temple Lane he spots a policeman whom he knew – Spargo asks what’s up, and the policeman ‘jerked a thumb over his shoulder, towards the partly opened door of the lane’ where there was the porter who had found the body. The bludgeoned body was that of an elderly man found with no money or identification, but with the address of a young barrister, Ronald Breton, scrawled on a piece of paper. Spargo is intrigued and takes on the case for his newspaper, not just as a reporter but as part of the investigation together with the somewhat pedestrian Detective Sergeant Rathbury of Scotland Yard. The case must be solved by finding not only the identity of the murderer but of the victim himself.

So, who was the author? Joseph Smith Fletcher (1863 – 1935) was born in Halifax, Yorkshire, the son of a clergyman who died not long after his son’s birth. Fletcher was brought up by his grandmother on a farm, educated in Pontefract and afterwards made some study of law. Aged 20 he took up journalism in London and worked as a sub-editor. Later he returned to Yorkshire, where first he wrote for The Leeds Mercury (using the by-line of A Son of the Soil) and then as a special correspondent for The Yorkshire Post (for which he covered the Coronation of Edward VII in 1902 and with which The Leeds Mercury later merged).

He started his non journalistic career by writing poetry, and then went on to write both fiction and non-fiction, particularly historical (he became a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society). His first book – there were more than 230 in all – was published in 1888, when he was 25. By 1914, when he wrote his first detective novel, he had had some ten books published. He was to go on to write over 100 detective novels, many featuring a private investigator who does not appear in Middle Temple Murder. Indeed, his output was so prolific he was called ‘The Dean of Mystery Writers’. He was an almost exact contemporary of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1859 – 1930), whose Sherlock Holmes stories began publication in 1887 with The Study in Scarlet (the last was published in 1927).

So why, you may well be thinking, is Middle Temple Murder important? To be honest, although Fletcher describes London in vivid and atmospheric detail, the book is not in the first flight of detective fiction writing, it is a bit wordy and the end is a bit rushed. But it is nevertheless a seminal work for three reasons. First, he created what came to be used as the basic template for writing detective fiction novels. Second, he may have created in Frank Spargo the first investigative journalist in fiction; sadly Spargo, whom many critics have praised, did not reappear in any of his other books. And third, it was extremely successful, especially in the USA where it was apparently publicly championed by Woodrow Wilson, President of the United States 1913-21, as a result of which Fletcher secured a publishing deal in the States. My own second-hand paperback copy was published there in 1980 and the blurb on the back glows –

This exciting, well-plotted tale is one of the great mysteries of the 20th Century. It remains a pleasure to read today, and though it is credited with influencing the modern vogue for the form, it appeals as much for its Edwardian flavour [sic] as for its modern detectional [sic] procedure…. [It] deserves to be in every mystery fan’s library.

Much of the action in the story takes place outside Middle Temple, but the descriptions of the Temple are fairly accurate. I assume that the entry where the body was found was one of the buildings on the east side of the top of the Lane – it may indeed have been the entrance to Hare Court. The Temple has of course changed over the last 100 or so years, not least because of war damage. The description of one set of chambers particularly sticks in my mind –

The old house in the Temple to which [Spargo] repaired and in which many a generation of old fogies had lived since the days of Queen Anne, was full of stairs and passages…. He knew that all the doors in the house were double ones, and that the outer oak in each one was solid substantial enough to be soundproof.

I am unaware of any other fictional murder in Middle Temple, though of course one of the most notable of writers in the crime genre, Cyril Hare, pseudonym of county court judge Gordon Clark (1900 –1958), was a member of Middle Temple (his nom de plume was a combination of Hare Court where he practised and Cyril Mansions where he lived) His Tragedy at Law (1942) is still seen as one the best whodunnits set in the legal world and has never been out of print.

Master Marilynne Morgan, a Bencher since 2002, has sat on the Executive, Estates, Finance and Wine Committees, and was the last Chair of the Catering Committee before becoming the first and last Master of the Kitchen; her term as Trustee of the Scholarship Funds ended in 2022. She was Lent Reader in 2012. She spent her career in what was then the Government Legal Service, latterly as Legal Adviser to major government departments.