Politicians and government leaders in almost every jurisdiction, worldwide, make frequent use of the term ‘Rule of Law.’ Sometimes this is done to encourage public accountability and sound government. Perhaps almost as frequently, at least in some authoritarian countries, the term is used to cover up abuses and shift the blame for failures of administration to those who have publicised or critiqued such failures. Take, for example, former Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte’s administration going after the nation’s leading independent news outlet, Rappler, for tax evasion, or the Chinese President publishing Xi JinPing’s Thought on the Rule of Law in an effort to recast it in line with his authoritarian approach. In the current American context, the term ‘Rule of Law’ has been referenced both in the indictment of former President Trump in the secret documents case and in defence, unfortunately, by Mr Trump himself.

The continued public reference to Rule of Law considerations, for good or ill, shows that the term remains at the strategic heart of what we want in a just, stable, and prospering society. But what does it mean? What factors are included in the substance of the term? Is it possible to measure it? However, we ultimately define it, can it apply to countries as diverse as Denmark and Saudi Arabia, with their different social norms and methods of conflict resolution? It is this writer’s strong belief that these questions, and the answers we provide for them, are central to whether modern democratic states can survive and prosper in today’s divided and polemical world.

One place to look for a fuller understanding of the Rule of Law, and its implications for society and governance, is the use of that term by various law-related institutions. For example, the American Bar Association (ABA) has as one of its four goals: ‘Advancing the Rule of Law’ (the other three goals being to ‘Serve our members, improve our profession,’ and ‘eliminate bias and enhance diversity’). As objectives under the Rule of Law Goal, the ABA includes: i) increase public understanding of and respect for the rule of law, the legal process, and the role of the legal profession at home and throughout the world; ii) hold governments accountable under law; iii) work for just laws, including human rights and a fair judicial process; iv) assure meaningful access to justice for all persons; and v) preserve the independence of the legal profession and the judiciary. This is an admirable approach to a complex topic and comports well with the outstanding and impactful global work of the ABA’s Rule of Law Initiative (ROLI), now Chaired by former US Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer and active in more than 50 countries. But this use of the term Rule of Law lacks the empirical research and scholarly analysis that would take it to the next level.

The US Federal Court System’s definition of the Rule of Law touches on many of the same issues and provides that the ‘rule of law is a principle under which all persons, institutions, and entities are accountable under laws that are publicly promulgated, equally enforced, independently adjudicated and consistent with international human rights law.’

For the United Nations, many of the same factors come into play in understanding, and promoting, rule of law principles: ‘the rule of law is a principle of governance in which all persons, institutions and entities, public and private, including the State itself, are accountable to laws that are publicly promulgated, equally enforced and independently adjudicated, and are consistent with international human rights norms and standards.’ This is further explained by the UN with reference to various constituent elements: accountability, protection of human rights, participation in decision-making, accessibility and transparency, separation of powers and distinction between the rule of law and the rule by law. This last point in the UN analysis is a particularly important one and has been flagged by numerous commentators over the years.

Another active participant in the discussion of what is contained under the Rule of Law rubric is the international law publisher LexisNexis, which posits that the ‘rule of law is the foundation for the development of peaceful, equitable and prosperous societies’ and includes four components: equality under the law, transparency of law, an independent judiciary, and an accessible legal remedy.

For the Law Society of England and Wales, ‘rule of law is the framework that underpins open, fair, and peaceful societies, where citizens and businesses can prosper. It is essentially about ensuring that i) public authority is bound by and accountable before pre-existing, clear and known laws; ii) citizens are treated equally before the law; iii) human rights are protected; iv) citizens can access qualified and predictable dispute resolution mechanisms; and v) law and order are prevalent.

Through its Rule of Law Forum, the International Bar Association (IBA) encourages and assists its membership to speak out in support of the Rule of Law. To better help the general public appreciate how people’s lives are affected when the Rule of Law is flouted, the IBA created a series of short videos that call attention to the human impact of government corruption, censorship, and political manipulation of the justice system. The campaign’s tagline is delightfully straightforward: ‘Look after the rule of law and the rule of law will look after you.’

The most elaborate and influential efforts to examine all the intricacies of the Rule of Law have come, however, from the World Justice Project (WJP) and its annual Rule of Law Index. WJP was formed in 2006 as an initiative of the American Bar Association by ABA President William H. Neukom. It became an independent entity in 2009. Its detailed analysis of the different aspects, or principles, of the Rule of Law are: i) accountability (the government as well as private actors are accountable under the law); ii) just law (the law is clear, publicised, and stable and is applied evenly. It ensures human rights as well as property, contract, and procedural rights); iii) open government (the processes by which the law is administered, adjudicated and enforced are accessible, fair and efficient); and iv) accessible and impartial justice (justice is delivered timely by competent, ethical and independent representatives and neutrals who are accessible, have adequate resources and reflect the makeup of the communities they serve.). WJP formed its principles in accordance with internationally accepted standards and norms, and then tested and refined them in consultation with a wide variety of experts worldwide. As a result of that process, the principles reflect an effort to include informal approaches to law that make the term Rule of Law applicable to a wider array of social and political systems.

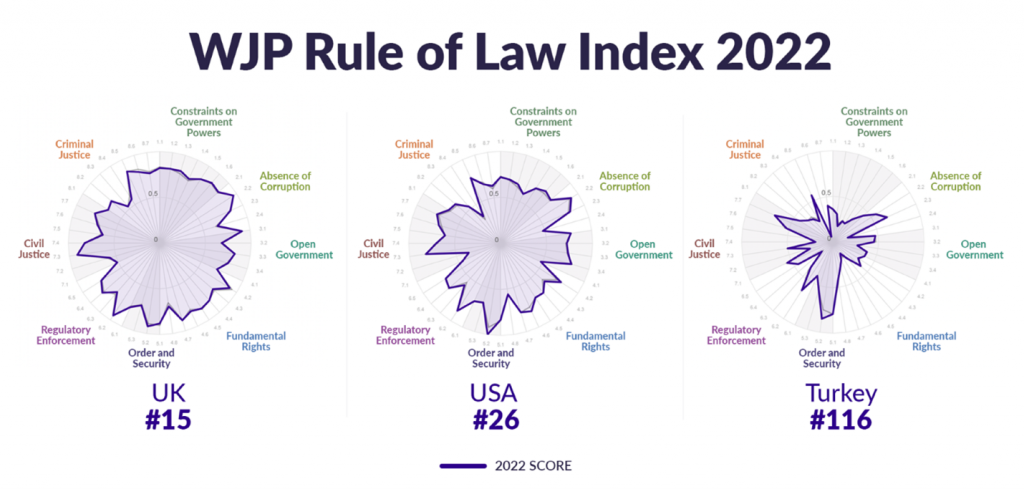

To further test the validity and universal coverage of these four Rule of Law principles, WJP has taken the innovative and ambitious step of constructing its annual Rule of Law Index, now covering more than 140 countries and jurisdictions. The Index measures the performance of each country on the basis of eight factors and numerous subfactors under each. The eight factors are: i) constraints on government powers; ii) absence of corruption; iii) open government; iv) fundamental rights; v) order and security; vi) regulatory enforcement; vii) civil justice; and viii) criminal justice. The Index that is created each year is based on national surveys of individuals in each country, as well as in-depth questionnaires to experts, including lawyers, judges, and scholars from each country. The surveys reflect both experiences and perceptions and the rigorous Index methodology has been validated by external institutions including the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre.

The findings in each WJP Rule of Law Index are often cited by government leaders, civil society groups and business decision-makers. Top Kosovo officials frequently cite the Index and their country’s recent progress in pressing the case for accession to the European Union, while former Pakistan Prime Minister Imran Khan has cited his country’s low Index ranking while alleging a government crackdown on his opposition party. Microsoft President Brad Smith says the Index has made a major contribution to the world and his company. ‘We can’t meet our customer’s needs without legal systems that are accountable, just, open and accessible, and impartial,’ he said at the 2022 World Justice Forum. Such references have helped inspire governments to address Rule of Law deficiencies and improve their country’s rankings in the Index.

To show the detail of the Index’s findings for various countries, included below are the spider graphs for three countries: the United Kingdom, the United States and Turkey, in which the results of the 2022 Index’s findings vary considerably.

In the overall Index rankings, every country has certain strengths and certain weaknesses in its Rule of Law performance. These are specific issues of which each country can be proud and specific issues on which each country can see that improvement is definitely needed. For example, the US scored comparatively poorly on both civil justice and criminal justice. In the overall rankings of 140 countries, the UK ranked 15th, the US 26th and Turkey 116th. In the 2022 WJP Rule of Law Index, Denmark and Norway had the highest rankings and Venezuela and Cambodia the lowest.

One of the most important features of the Rule of Law Index is its availability to the general public, globally, to inform the public’s views and ultimately their choices in electing governments and enacting policies in support of the Rule of Law. Examples of the immediate relevance of the Rule of Law to issues of vital national importance come up almost everywhere, including in the most developed states, where previously Rule of Law adherence was most firmly entrenched. In the recent criminal indictment of former US President Donald Trump concerning classified documents, the US special counsel, Jack Smith, noted on Friday 9 June 2023, that: ‘adherence to the rule of law is a bedrock principle of the Department of Justice. And our nation’s commitment to the rule of law sets an example for the world. We have one set of laws in this country, and they apply to everyone.’ And in the UK, the Rule of Law has been repeatedly cited by those opposing government proposals to deport migrants seeking refuge. ‘I certainly would think that it was a step of the absolute last resort and sets an extraordinarily bad example for a country committed to the rule of law to say the government can ignore a judicial order,’ former Lord Chief Justice Thomas of Cwmgiedd told the BBC.

The lesson for justice systems, governments, the public and the media is that how we define the Rule of Law matters. The use of the term needs to be examined – both in terms of who is using it and why. The Rule of Law is not just whatever someone claims it to be. By engaging in robust conversations about what Rule of Law is and what it is not, governments and other institutions, as well as members of the media, the academy, and the legal profession can help protect, sustain, and strengthen it . The Rule of Law, and how we use the term, matters because it is fundamental to peace, justice, respect for human rights, effective democracy, and sustainable development.

Master James R. Silkenat is a past President of the American Bar Association. He was a partner in the New York office of Sullivan & Worcester, is a former Legal Counsel at the World Bank Group’s International Finance Corporation and is the co-editor of Building the Rule of Law: Firsthand Accounts from a Thirty-Year Global Campaign.