Book Review by Master Elaine Banton

Alexandra Wilson’s book, In Black and White is a thrilling exposé of race and class, as well as resourcing and how all these factors feature in the criminal justice system, delivered with her fresh personal perspective. Unafraid to hit controversial topics head on we benefit from her fresh, honest approach to the issues at the heart of it.

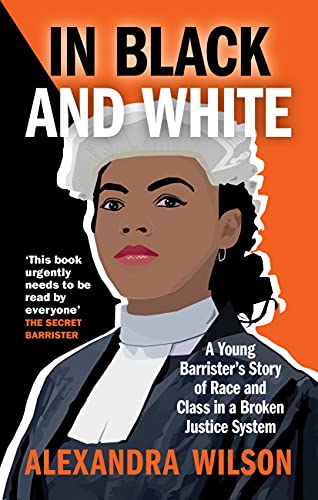

To borrow a device from an unconscious bias test, if you close your eyes and imagine a barrister, you might not immediately conjure up a picture of a young Black or mixed-race woman.

Alexandra Wilson is a young, mixed-race, state educated junior barrister from Essex, whose honest account of her experience training and working as a pupil barrister to tenancy, delivered In Black and White, has quite rightly, enlightened, resonated and inspired in equal measure.

I first met Alexandra a couple of years ago when we both spoke at the Middle Temple Black History Month event, where she recounted an experience in the robing room which left much to be desired. She was told by a senior White male criminal barrister, apropos of nothing, that Black women, ‘could just become judges’. This type of open, unflinching account is synonymous with the passion and verve that Alexandra approaches the subject of diversity in the law.

The devastating murder of her cousin Ayo in an unprovoked stabbing incident profoundly impacted her life and she is compelled to a career in law to be part of improving a system riddled with disparities around race and class. Ayo, 17 years old, was not in a gang but was a young man mistaken for someone else; simply in the wrong place at the wrong time. Alexandra went on to study PPE at Oxford University and was deservedly awarded Middle Temple’s first Queen’s Scholarship.

Alexandra deftly leaves no stone unturned as she chronicles her experiences from school to Oxford university, where she was often ‘othered’ by contemporaries, the implication being that she should not really be there, because of her state school education.

Whilst recounting her journey to pupillage as a pupil barrister, Alexandra highlights issues around the perplexing escalation of some matters to criminal courts, such as involving a neighbour dispute over flowers, a 14-year-old girl and a court hearing. Another being the invidiously frustrating resource lottery around the availability of hospital orders where without capacity prison lies.

Alexandra brings to the fore that all too often cases that could and should have avoided going to court are funnelled through the over-burdened, straining criminal justice system, putting into sharp focus the need for more out of court disposals and other alternatives.

The poignantly bleak description of the youth court where the defendants were all Black, and the apparent disconnect between the barristers and judges were all White, told a tale that hallmarked the disproportionate representation of Black and ethnic minorities throughout a criminal justice system that all too often alienates. The statistical analysis, fully supporting the biases against those who are not White, middle-class males, familiar to many, is adeptly woven into the story in accessible fashion, so that all may grasp these thorny issues.

Alexandra was fortunately able to turn her sense of being an impostor in a privileged environment into a fundamental positive aspect by the knowledge that having a different or non-traditional background was a strength. When working with clients, significantly, Alexandra demonstrates how she was able to bridge the gap and establish a rapport with clients from lower socio-economic and/or Black and ethnic minority backgrounds who did not often feel understood before.

Of her own personal journey from the intersectional position as a young mixed-race woman, she recounts the incredulity shown by a White male barrister of her socioeconomic mobility which points to the perception held by many that the combined effect of race, class and sex will prove too high a hill to climb. Again, this encounter will resonate with many past and present.

There are many moving anecdotes too, such as the touching vignette of her nan accompanying her to buy her wig and gown. The female barrister who reaches out and passes on her contact details, giving her positive and encouraging feedback regarding her notes is also well recognisable of the Bar. Alex also covers the vexed issue of retention and progression of female barristers and how this is hindered by the frequent need to work antisocial hours with a lack of support. A factor that post Covid-19 we have seen come into sharp focus with extended operating hours is likely to further exacerbate the somewhat precarious, hard fought, existing diversity at the Bar.

Alexandra last year used her platform to highlight her attending court and being mistaken for the defendant three times in one day (in a civil context this is being mistaken for anyone but the barrister). This is unfortunately an all too familiar occurrence for barristers from Black and ethnic minorities. Such issues powerfully resonate with themes in her book.

Approach Alexandra Wilson’s book with an open mind and be prepared to grapple topical issues around race, class, and sex, as well as resourcing and how all these factors feature in the criminal justice system. Her gripping and energising narrative starkly conveys the importance of diversity within the legal profession and the criminal justice system.

If a strong Bar is one truly representative of all the rich, diverse talent within society, then we do really have some way to travel. In a post George Floyd world where anti-racist statements abound and the profession seeks to communicate more effectively around race, Alexandra’s searingly honest, intelligent account will help to break down barriers and is a significant contribution to the education required to engender lasting, meaningful systemic change. It will also undoubtedly prove an inspiring addition to all school libraries, particularly for those from more underrepresented groups at the Bar. Alexandra has gone on to establish Black Women in Law (BWIL), offering networking, mentoring and education, as well as co-founding One Case at A Time (OCAAT), to facilitate access to justice funding and legal representation for minorities with a focus on Black people. In Black and White is currently under option to be made into a drama and Alexandra is also writing another book (crime fiction), due to be published next year, so watch this space.

Master Elaine Banton is a Bencher at Middle Temple. She is an employment, equality and discrimination practitioner at 7BR, was Co-Chair of Middle Temple’s Race Equality Inclusion and Anti-Racist Committee and is Co-Chair of the Bar Council’s Equality Diversity and Social Mobility Committee.